A new measure purports to gauge city attractiveness by measuring whether local college graduates stick around. But these raw numbers can be a misleading indicator, and we’ll show how it can be adjusted to more accurately measure how good a job a city is doing of producing and retaining talent.

There’s powerful evidence that the educational attainment of population is the single most important factor affecting a region’s economic success. We’ve observed that you can explain about 60 percent of the variation in per capita incomes among metropolitan areas simply by knowing what fraction of the adult population has completed a four-year college degree. While there are many ways to increase a region’s talent base, one core strategy is doing a great job in educating your own young people—and then building the kind of community that they will want to stay in.

Does retaining local graduates mean you’re stemming brain drain?

But measuring the migration of talented workers can be tricky. In a recent article in CityLab, “The U.S. Cities Winning the Battle Against Brain Drain,” Richard Florida presents some findings on the tendency of college graduates to stay in the metropolitan areas where they got their degrees. Using data cleverly assembled by the Brookings Institution’s Jonathan Rothwell and Siddharth Kulkarni from LinkedIn profiles, Florida shows which cities have the highest and lowest levels of retention of college graduates.

Some of the results are, at least at first glance, surprising. According to the Brookings figures, the Detroit metro has retained 70.2 percent of its graduates—one of the highest figures in the nation. This seems surprising, because the Detroit metro area actually experienced a 10 percent decline in the number of 25- to 34-year-olds with a four-year degree between 2000 and 2012 (as we documented in our report, “Young and Restless”).

Conversely, fast-growing tech powerhouse and hipster haven Austin, Texas ranks among the ten lowest cities, handing on to just 38.2 percent of its recent college graduates.

What’s going on here?

Well, it turns out that this particular set of college graduate retention statistics tell us a lot more about the size and characteristics of the local higher education system than they do about the attractiveness of the local city, either in terms of its amenities or its job prospects. In other words, it’s more about the supply of college graduates produced by local colleges and universities than the demand of college graduates for living in a particular city.

Different cities have different kinds of higher ed systems

To understand why, think about two kinds of cities. In a college town like Madison, WI or State College, PA—or even larger cities with high concentrations of college students, like Boston or Austin—the local colleges or universities are effectively a big export industry, producing far more degrees than the local economy demands, and then shipping them out to a statewide, regional or national market. Students come to Austin from all over to get a degree at the University of Texas, and many return to their hometowns—or relocate somewhere else for a job—immediately after graduating.

In other cities, the local colleges and universities aren’t so “export-oriented.” In these cities, local higher education mostly serves the local market. As a result, graduates in these cities are more likely to remain in the city where they studied, because that’s where they started out. These cities will have a much higher “retention rate” than export-oriented higher education markets, but that has everything to do with who’s coming in, and much less to do with how attractive graduates find the city when they get out. The key here is that the difference is in thehigher education institutions, not the cities they’re located in.

As part of our research for the Talent Dividend Prize—a competition funded by the Kresgeand Lumina Foundations—to see which US metropolitan area could achieve the largest increase in the number of two- and four-year college degrees awarded to local students over a four-year period, we assembled data from the Integrated Post Secondary Education Data System (IPEDS) on the number of college degrees awarded in large metropolitan areas. Among the 50 largest metropolitan areas, the number of BA and higher degrees awarded in 2012 varied from a low of 2.8 (in Riverside, California) to a high of 17.5 (in Phoenix, Arizona). The typical large metropolitan area grants about 8 BA or higher degrees per 1,000 population on an annual basis.

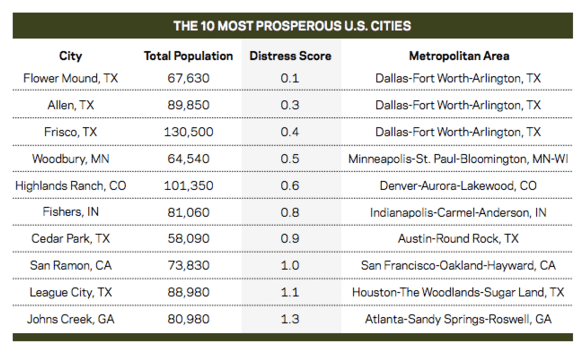

In the following table, we’ve matched our BA degree award rate data with the information provided by Brookings on the BA retention rate for the ten highest rated and ten lowest rated metropolitan areas.

There’s an obvious pattern here: Metropolitan areas with high levels of BA retention have very small higher education establishments (as measured by the number of BAs awarded per 1,000 population. Conversely, metro areas with low levels of BA retention have, on average, much higher levels of BA award granting. This is exactly what we’d expect when thinking about cities that are home to large universities that attract many students from elsewhere.

To get a better sense of whether a metro area is experiencing a brain drain or a brain gain, when can combine these data. The final column of the tables does that by multiplying the number of BA degrees issued per 1,000 population by the BA retention rate. This is a rough estimate of the number of additional BA degree holders (per 1,000 population) who reside in a metro area after graduation.

These data come closer to our intuition about which places are gaining talent. Larger metropolitan areas (New York, Los Angeles) have relatively high rates of local BA growth (5.9 and 5.2 per 1,000 population respectively. Cities with strong tech economies, like San Jose (5.7) also do well on this measure. Conversely, economically challenged places don’t do as well—Detroit’s local BA per 1,000 population rate is 2.9; even though it does a relatively good job of retaining those who graduate locally, the size (or at least output) of local higher education institutions is so small (relative to the size of the region), that it is not gaining talent as much as the other areas on this list.

So, as it turns out, the retention rate of college graduates is at best an incomplete indicator of whether cities are stemming the tide of a brain drain (or not). If local higher education institutions are small, and chiefly serve students from local high schools, a high retention rate is not necessarily a sign of success. Conversely, if your area colleges and universities are large and attract students from around the nation, a low retention rate may not be a sign that you’re doing poorly.

Cities matter even before graduation

As these data make clear, the competition for talent begins long before students receive their bachelor’s degree. The number and kind of local colleges and universities is a decisive asset in positioning a city to attract talent.

At least a portion of the brain drain dynamic occurs when students decide where they are going to college. For metros like Detroit, where there are relatively fewer local universities than in the typical metropolitan area, more students are going to leave the local metro area to get a degree. And even if a high number of those who study locally stick around (as appears to be the case) that effect can easily be swamped by those who leave for college and never return. (Detroit’s college and universities award about 4 degrees per 1,000 population annually; compared to about twice that many for the typical metropolitan area). Because local universities and colleges are so small, relative to the average, Detroit has to retain 100 percent of its graduates to have as many new BA degree holders, proportional to its population, as a metro see half of its graduates migrate away.

For some students, the city in which their university is located can be an important factor in deciding where to enroll. Part of Philadelphia’s “Campus Philly” recruiting program—aimed at out of town students— has been to promote the city’s urban amenities as one of the advantages of choosing one of its many local colleges and universities. The program follows up with activities and internships that look to connect students to the community while in school and after graduation.

Nurturing, attracting and retaining talent are all mutually reinforcing strategies for bolstering the regional economy. Cities need to pay attention to the size and quality of their colleges and universities, as well as to build the kind of communities that they (and other well-educated persons) will want to live in. Because this process is so multi-faceted, no single measure captures all of the dynamics at play. What we’ve provided here shows that a simple retention rate is not enough to understand whether a city is doing well in attracting and retaining college grads.

Data notes

The numbers for Phoenix are something of an anomaly. The University of Phoenix, the nation’s largest distance learning institution reports its BA degrees to IPEDS as being awarded in the Phoenix metropolitan area, even though nearly all of its students are located in other metropolitan areas. This tends to greatly exaggerate its local output of graduates.