The fundamental injustice of pollution from urban freeways

Item: In the past two years, Portland Public Schools has spent nearly $12.5 million of its scarce funds to clean up the air at Harriet Tubman Middle School. This money will buy an expensive state-of-the-art air filtration system that will make the air inside the school safe for students to breathe. Scientists from Portland State University, who conducted an air quality assessment of the site–at a cost of an additional half million dollars–have warned the students against exercising outside because of poor air quality.

And make no mistake, pollution from cars is a threat not just to the health of students, but to their ability to learn as well. A recent study shows that pollution from cars and trucks lowers student performance in schools near highways. Students attending schools located near and downwind from busy highways had lower rates of academic performance, higher absenteeism and higher rates of disciplinary problems than those attending less polluted schools. The more traffic on nearby roads, the larger the decline in scores on state standardized tests.

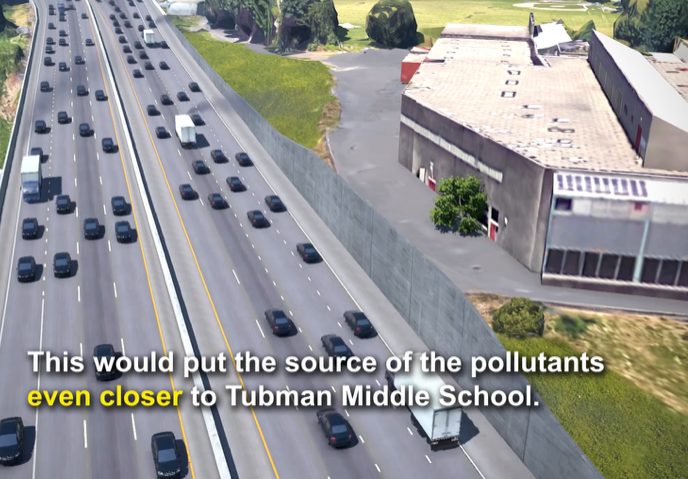

Tubman School faces a further increase in air pollution from the proposal of the Oregon Department of Transportation to spend a half billion dollars to widen the portion of Interstate 5 that runs right by the school. The freeway-widening project will cut away a portion of the hillside that now separates the freeway from the school, moving the cars and trucks still closer to the building, and also increasing their volume—and the volume of pollution they emit.

So, here’s a question: Why is the school district paying for the pollution controls? Why aren’t the 120,000 vehicles that drive past the school every day paying for it? They’re the ones creating the pollution and benefitting from the freeway.

As we pointed out earlier at City Observatory, the gravity of this question is underscored by the huge disparity in the demographics of those who use the freeway, especially at peak hours, and those who attend Tubman Middle School. Peak hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County, Washington have average household incomes of $82,500; and 75 percent of them are white, non-Hispanic. More than two-thirds of Tubman students are people of color; and half the student body is poor enough to qualify for free or reduced price meals.

In a very real sense, what this does is make students pay for the costs of pollution. The millions and millions of dollars being used to pay to install and operate air filters is money that isn’t available to pay for books and teachers. Meanwhile, freeway users get a free ride. This is plainly unfair.

Who was here first?

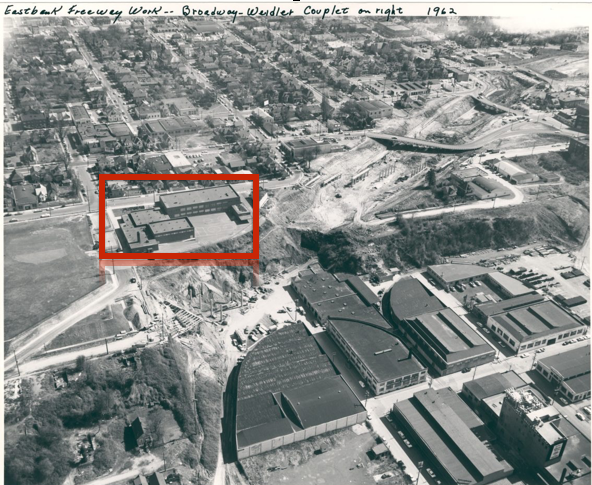

So why did Portland Public Schools build a school next to a freeway in the first place? If they did so, then clearly, they must bear a big part of the blame for the fact that kids have to breathe here. What makes this whole situation even more unfair is that, actually, the school was here first. Lest there be any doubt, take a look at this aerial photo showing the construction of Interstate 5 in 1962. (The Tubman School is outlined in red).

When it was built, Tubman School stood on a bluff, overlooking the city of Portland. The Oregon State Highway Department, following the advice of Robert Moses, cut away the hillside and dropped the freeway right next to the school. So if the school was there first, why isn’t ODOT paying to clean up the air its students have to breathe?

Well, back in the 1960s, highway departments, Oregon’s included, seldom paid for any of the damage they did to cities. As we’ve noted, the Oregon Department of Transportation obliterated hundreds of homes in this neighborhood and did nothing to replace the lost housing. Back then, air pollution was a greatly under-appreciated problem. Years after I-5 was built, ODOT did install some concrete walls to attenuate freeway noise in North Portland, but as to air pollution, nothing.

The Coase Theorem

Here’s where things get a bit wonky, at least for economists. There’s a famous conjecture in economics called the Coase Theorem which at its root is based on a story very much akin to that of the the freeway and the school. Coase’s story is about a farmer and a railroad, in this case, an old fashioned steam-powered railroad, with smoke-and-spark belching engines. Sparks from the steam engines would fly into the farmer’s field, burning her crops. Coase mulled over the economics of who should pay whom for the damages, and what would be an efficient and fair outcome. He concluded, that it didn’t actually matter, as long as either one party or the other had clear property rights. Let’s turn the microphone over to University of California economist Brad DeLong, who picks up the story, first summarizing Coase’s argument, then pointing up a huge flaw.

The brilliant Ronald Coase . . . was interpreted to have argued that pretty much any arrangement of property rights will do about as well as any other and the government should simply step back.The canonical case adduced was the locomotive that occasionally throws off sparks that burn the nearby farmer’s crops. If the railroad has a duty of care not to burn the crops, Coase said, the railroad will attach spark-catchers if it is cheap and makes sense to do so – and the railroad will pay damages and settle in order to avoid being hauled into court on a tort claim if it is expensive and doesn’t make sense to do so. If the railroad has no duty of care, Coase said, then the farmer will offer to pay the railroad to install spark-catchers – and spark-catchers will be installed if the potential damage to the crops is greater than the cost of the spark-catcher and it makes sense to do so, and spark-catchers will not be installed if the damage to the crops is less than the cost.

Thus the same decisions will be made whatever the property rights – as long as there are settled property rights. If there are not settled property rights, then the crops burn and lawyers grow fat. But as long as there are property rights, the market will work fine. Maybe the widows and orphans who own railroad shares will be wealthier under one setup and maybe the farmers will be wealthier under the other, but that is rarely a matter of great public concern.

Now this argument has always seemed to me to be wrong. If there is no duty of care on the part of the railroad, it has an incentive not just to threaten not to install a spark-catcher, but to design and build the most spark-throwing engine imaginable – to make sure that the firebox is also a veritable flamethrower – and then to demand that the farmer bribe it not to set the fields on fire. What economists call “externalities” are rife, and call for the government to levy taxes and pay bounties over wide shares of the economy in order to make the incentives offered by the tax-and-bounty-augmented market the incentives that it is good for society that decision-making individuals have. Cutting property rights “at the joints” to reduce externalities is important. But it will never be efficient: what economists call Pigovian taxes and bounties make up a major and essential part of the business of government.

And in fact, while DeLong’s point about “a veritable flamethrower” seems like hyperbole, that’s pretty much exactly what the Oregon Department of Transportation is doing here: Having already polluted the air near Tubman, it is doubling down on its earlier transgression—in part because of the moral hazard: coping with the pollution isn’t it’s problem—it’s neatly shifted all of the costs of pollution to others–in this case the students and Portland Public Schools.

As a matter of both justice and efficiency, the Oregon Department of Transportation–and through them, the users of Interstate 5—ought to be required to pay for cleaning the air at Tubman. Failing to impose these costs on ODOT leads it to falsely and unfairly under-value the lungs of these students, and to make a further investment that will make this problem worse. If ODOT had to bear these costs, it would likely look at the freeway widening project very differently, and instead, consider alternatives that produce smaller amounts of emissions (and might even consider ways to reduce traffic, rather than increasing it).

Making kids pay for freeway pollution—and in fact, pay twice, first by breathing polluted air, and then second, by having to pay for the cost of cleaning it–is both wrong and inefficient. And like Coase’s example of the farmer and the locomotive, there’s actually a bigger issue here: More generally, we should be insisting that car users pay the costs that they impose on others. The reason why pollution, sprawl and even traffic congestion are so bad is because we’ve radically under-priced car travel, in essence subsidizing people to do things that degrade our cities and communities. Assigning the responsibility correctly, and getting the prices right can improve fairness, and make our cities better places to live.

Editor’s note: Commenters are puzzled that they can find no record of Harriet Tubman school prior to the 1980s. The building now named Harriet Tubman was originally built as Eliot Elementary School in 1952. Eliot Elementary was subsequently merged with Boise Elementary—due to declining population in the neighborhood, caused in major part by the construction of the freeway. The Eliot/Tubman building has been owned continuously by Portland Public Schools. (This note added on March 8, 2019).

[…] Source: cityobservatory.org […]

[…] Why do poor school kids have to clean up rich commuters’ pollution? 12 by oftenwrong | 0 comments on Hacker News. […]

[…] https://cityobservatory.org/why-do-poor-school-kids-have-to-clean-up-rich-commuters-pollution/ […]