A newly revealed ODOT report shows the redesign of the I-5 Rose Quarter project will:

- creates a dangerous hairpin turn on the I-5 Southbound off-ramp

- increase crashes 13 percent

- violate the agency’s own highway design standards

- result in trucks turning into adjacent lanes and forcing cars onto highway shoulders

- necessitate a 1,000 foot long “storage area” to handle cars exiting the freeway

- require even wider, more expensive freeway covers that will be less buildable

A project that ODOT has falsely billed as a “safety” project—based on a high number of fender benders—actually stands to create a truly dangerous new freeway off-ramp, and at the same time vastly increase the cost of the project, while making it harder to build on the project’s much ballyhooed freeway covers.

Earlier, we revealed that the redesign of Oregon DOT’s proposed $1.45 billion Rose Quarter Freeway widening project will a hazardous new hairpin off-ramp from Interstate 5, endangering cyclists.

The safety analysis for the project’s Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement confirms our concerns that ODOT is building a “Deadman’s Curve” off-ramp: The agency estimates the new ramp will increase crashes 13 percent compared to the No-build, and that the design of the off-ramp violates ODOT’s own Highway Design Manual.

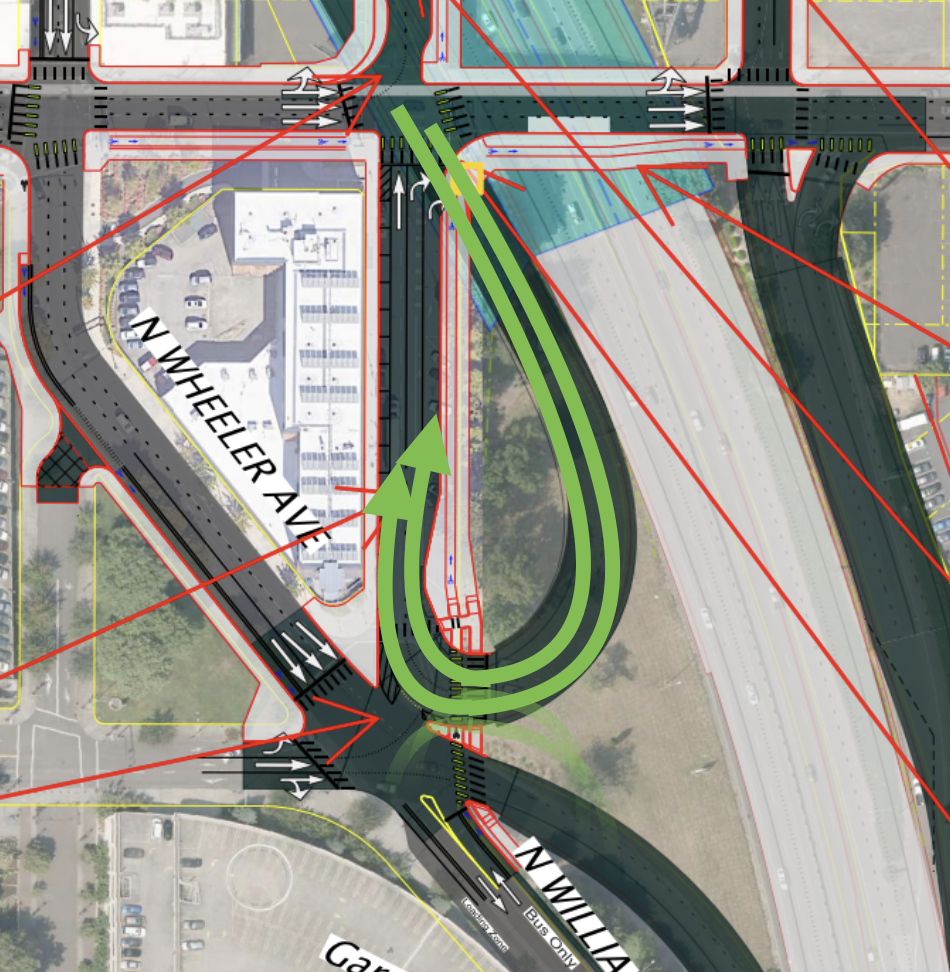

As part of its redesign of the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway project, ODOT has moved the Southbound off-ramp from I-5, which is now located just North of NE Broadway, to an area just next to the Moda Center, and immediately north of the existing I-5 south on-ramp. The new ramp fits awkwardly into the existing street grid, and the most troublesome feature is a hairpin turn for traffic exiting the freeway: I-5 traffic traveling southbound and leaving the freeway has to do a tight 210 degree turn onto Northbound Williams Avenue. The proposed off-ramp would have two lanes of freeway traffic negotiating the hairpin turn on to N. Williams Avenue (shown as green arrows in this diagram).

Just a week ago we wrote a scathing critique of the Oregon Department of Transportation’s proposed redesign of the I-5 Rose Quarter project. The agency is building a new and dangerous off-ramp, that creates a hairpin turn on a freeway exit, funnels traffic across a major bike route, and causes longer travel on local streets. That’s pretty bad.

But the reality is much worse. Don’t take our word for it. Take ODOT’s. Though its shrouded in intentionally opaque bureaucratic language, it’s clear that the engineers at OregonDOT know this is a very unsafe project. And not just unsafe for bikes and pedestrians on local streets: the new ramp configuration creates a dangerous, and higher crash rate facility for cars and trucks

The agency’s safety analysis is contained in a technical safety report, dated, August 15, 2022, but publicly released just last week. It is worth quoting at length:

Under the HSM method, the number of crashes which may occur on a ramp is sensitive to geometric conditions, traffic volume, and length of the ramp. There are no major changes in geometry in the I-5 southbound exit ramp between the No-Build and Build conditions, hence they have similar forecast crash rates. However, as proposed in the Revised Build Alternative, relocating the I-5 southbound exit-ramp connection to the local system from N Broadway to NE Wheeler Avenue would increase the ramp length from approximately 1,000 feet in the No-Build conditions to approximately 2,000 feet in the Revised Build conditions, which would provide 1,000 feet of additional traffic queue storage. The new ramp design also includes wider shoulders than existing conditions. Based on the HSM, the forecast crash rate at this location would be approximately 13 % higher than the No-Build and Build condition. In the HSM, the number of crashes on a facility is highly sensitive to volume and length. As the length of this ramp increases, the forecast number of crashes increases and therefore so too does the crash rate. However, from a traffic operation perspective, the additional storage on the I-5 southbound exit-ramp would reduce the potential for queue spill-back onto the freeway. Under the No-Build Alternative, queue on the exit ramp is expected to propagate upstream onto the freeway mainline, creating a safety concern. The additional storage provided in the Revised Build Alternative would be able to accommodate the queue on the ramp without encroaching onto the freeway. This is particularly beneficial during peak hours and event conditions. In addition, the lengthening of the ramp will allow motorist to decelerate to a safer speed allowing them to safely navigate through the horizontal curve.

The final 250 feet of this ramp includes a horizontal curve prior to the ramp terminal intersection. The proposed curve would not meet ODOT’s HDM minimum radius for exit ramp curves and could also result in truck off tracking that extends outside of a standard travel lane. Therefore, to mitigate these considerations, the design detail of this curve would include wider shoulders and lanes than other sections of the ramp. Adequate delineation, signing, markings and lighting to inform drivers of the sharp curve as they approach the ramp terminal intersection would also be considered. These design treatments would be refined in the design process as the project proceeds. Figure 11 shows the existing N Williams Avenue/ NE Wheeler Avenue/ N Ramsay Way intersection and the lane configuration for the proposed I-5 southbound terminal.

There’s a lot to unpack here, and it’s written in a way as to be opaque and misleading. Let us translate it into English:

- We’re building a freeway off-ramp with an extreme (210 degree) hairpin turn (“the final 250 feet . . . includes a horizontal curve”).

- That’s going to increase the number of crashes by 13 percent above doing nothing, and our previous design.

- The hairpin turn and crashes will cause traffic to back up on the freeway off-ramp and could jam the freeway, but don’t worry, because we’ve doubled the length of off-ramp (from 1,000 feet to 2,000 feet) so that it will be long enough to serve as a parking lot for those exiting the freeway (“queue on the exit ramp . . . additional storage”)

- The turn is so tight that trucks can’t negotiate it without crossing out of their lane, but don’t worry, because the shoulders will be wide, giving cars plenty of room to dodge wide-turning trucks. “truck off tracking . . outside a standard travel lane”

- The hairpin turn is so severe that it violates our agency’s own standards for road design (the same standards we use to refuse to build bike lanes and provide pedestrian access). (“does not meet ODOT’s HDM minimum radius for exit ramp curves.”)

- We know the hairpin turn is dangerous, so we’ll think about putting in big warning signs and flashing lights. “Adequate delineation . . . to inform drivers . . .would be considered”).

More Dangerous, More Expensive, and Less Buildable

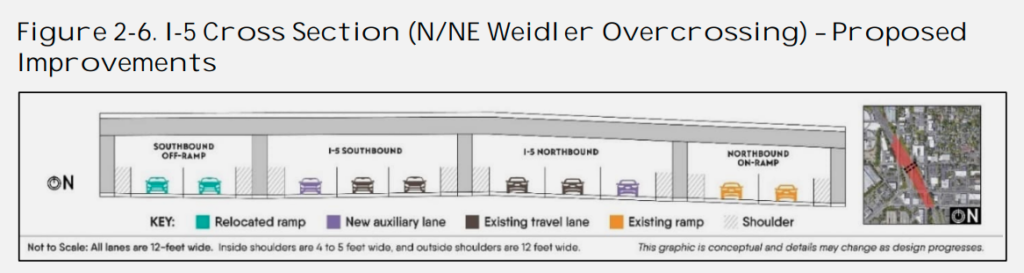

And there’s one more kicker that isn’t really mentioned here. Because the I-5 southbound ramp is now Nouth of Broadway and Weidler, moving the ramp South requires that the freeway be widened even further to provide two ramp lanes that reach all the way to NE Wheeler and the MODA center. Those lanes now have to go underneath Broadway and Weidler. That means that the additional one-thousand feet of off-ramp length would mostly be underneath one of ODOT’s much ballyhooed highway caps. In the diagram below, the two extended Southbound on-ramps are shown on the far left (with turquoise cars).

The proposed cost of the Rose Quarter project has tripled to nearly $1.45 billion, chiefly because of ODOT’s additional widening and the concomitant escalation in the cost of freeway caps. The caps are extraordinarily expensive, and their expense increases exponentially with added width. Routing two thousand-foot long on-ramps under the structure increases the needed with of the structure by at least 30 feet, and likely more. And that not only increases its cost, but the added width of the structure makes it more difficult to build a structure that could accommodate buildings. (As we noted earlier, ODOT says this portion of the freeway caps could handle buildings no higher than three stories (and such buildings would have to be “lightweight.”)

We have rules against such things: but they don’t apply to us.

The safety report makes a cryptic reference to something called the “HDM”: saying the dangerous hairpin turn “does not meet ODOT’s HDM minimum radius for exit ramp curves.” The “HDM” is Oregon’s Highway Design Manual that specifies all of the standards that govern the construction of major roadways and which sets the maximum radius of turns on roadways and off-ramps. For obvious reasons, tight-corners and blind turns create serious safety hazards. Freeway design standards are supposed to create roadways where crashes are less likely. ODOT is proposing to simply ignore its own rules and build this dangerous on-ramp.

ODOT can’t even apply its standards consistently. It asserts for example that it must build “full 12-foot” shoulders on much of the Rose Quarter project, ostensibly to improve safety. But its design manual doesn’t require such wide shoulders, and in fact, the agency has gotten recognition from the Federal Highway Administration for its policies that allow narrower shoulders on Portland-area freeways. In the same breath it touts widening shoulders (not required by its rules) as a safety measure, it gives itself an exemption from its own rules that explicitly prohibit dangerous hairpin turns on freeway off-ramps.

Transportation agencies routinely use their design manuals and similar rules to prohibit others from doing things. We can’t build a crosswalk or a bike lane in that location, because it would violate our design manual. That’s the end of a lot of safety improvements. Just last week, in Seattle, the city transportation department had dawdled for years with an application to a paint a crosswalk at a dangerous local intersection, acted overnight to erase one painted by fed-up local neighbors–citing non-compliance with similar rules.