What City Observatory did this week

1. The abject failure of Portland’s Climate Action Plan. Last month, Portland issued the final report on its 2015 Climate Action Plan. It emphasizes that the city took action on three-quarters of the items on the plan’s checklist, but glosses over the most important measure of results: the fact that Portland’s carbon emissions have actually increased in the past five years.

The City’s adopted 2015 Climate Action Plan called for putting Portland on a path to reduce greenhouse gases by a cumulative 25 percent from 1990 levels by 2020, but instead, emissions increased, and the city is stuck only 15 percent below 1990 levels. A newly issued “final” progress report on the 2015 plan mostly papers over this failure, and the reasons for it (increased driving due to cheaper gas). Portland has now adopted a “Climate Emergency Declaration” that sets an even more ambitious goal (a 50 percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2030), but hasn’t done the math or spelled out the steps that will be needed to achieve that goal. Instead, it mostly promises to convene a new conversation about climate which will be more equitable and inclusive, starting in the fall of 2020.

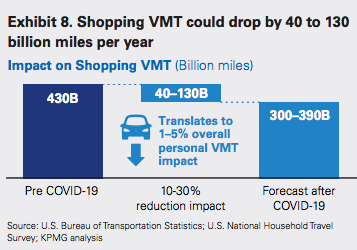

2. Auto industry experts forecast a permanent decline in driving and car sales. KPMG, management consultants to auto makers and their suppliers, has taken a close look at changed behavior in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Many more of us are working at home, and shopping on-line, trends that KPMG expects to translate into permanent changes in behavior even after the pandemic subsides. For example, they estimate that car travel associated with shopping could decline by 10 to 30 percent, eliminating 40 to 130 billion miles of vehicle travel each year.

Less car driving means lower car sales—and less lucrative car repair—but also means fewer crashes, injuries and deaths and less pollution. KPMG is warning its clients to prepare for a smaller auto market in the years ahead. Another groups that should pay attention to these forecasts is highway builders: Less driving means less need for new and wider roads. Hopefully, lower gas tax receipts are already sending that message.

Must read

1. Exclusive communities deepen metropolitan inequality. Brookings Institution’s Jenny Schuetz has a timely look at the way that exclusionary practices in some suburban jurisdictions drive metropolitan inequality and segregation. Schuetz explores the relationship between housing affordability and racial and ethnic composition of neighborhoods in cities in four large metro areas. She finds that exclusive suburban jurisdictions effectively exclude minorities by driving up rents. As she explains:

Whether or not expensive communities intend to bar entry to lower-income households, high housing costs are as prohibitive a barrier as more overt forms of discrimination. As long as there are substantial racial gaps in income and wealth, expensive communities will effectively be off limits to most Black and Latino households—as well as to renter households of all races.

The result is the most expensive cities in any metro area tend to have far fewer people of color than the overall metro area. Here are data for four large metros: Dallas, Detroit, Los Angles, Washington

2. The high (and inequitable) cost of city parking. Writing at the Washington Post, Ike Brannon, channelling his inner Donald Shoup, calls out the high social and environmental costs and inequitable impacts of the district’s under-priced street parking. Residents pay just $35 a year for a street parking permit, well below the market value of parking (as high as $2-3,000 per year in the Adams-Morgan neighborhood). Car owners are, on average much wealthier, and much more likely to be white than the average DC resident, meaning that this subsidy is delivered chiefly to higher income households, and is unavailable to those who can’t afford (or choose not to have) a car. But it isn’t just that people when out cars don’t benefit from under-priced parking, they pay an added cost in terms of worse transit service.

. . . the ubiquity of parked cars slows down buses. For example, the L2 from Woodley Park to Farragut has five stops where a handful of parked cars can delay the bus by one to two minutes. The result is that thousands of bus riders lose five to seven minutes each day (and that’s one way) to accommodate 20 to 25 car owners.

In addition, the obsession with parking supply is a chief reason for NIMBY opposition to new housing. More residents would mean more competition for free or under-priced parking, so existing residents push to assure plenty of parking by blocking more housing. The result is that everyone pays higher rents because not enough housing is built to accomodate all those who would like to live in urban neighborhoods. Free and under-priced parking is the scourge of healthy, livable and fair cities.

New Knowledge

Why the ward system leads to higher rents. Many cities elect their governing bodies by single member districts. Voting rights advocates have pushed for single member districts as a way to secure representation for geographically concentrated minorities, and courts have ordered some cities to replace their “at-large” City Councils with members elected by district. But single member districts have the pernicious effect of amplifying the “NIMBY”—Not in my backyard—dominance of local land use decisions. Unlike city councilors elected city-wide, members elected ward tend to be especially sensitive to the most localized aspects of decisions. By rule or custom, many ward-systems grant a personal veto—in Chicago “Aldermanic privilege”—for all land use decisions in their district.

While this effect is well-known in practice, there’s been little systematic investigation of the cumulative effects of ward-system on housing supply, until now. Evan Mast, of the Upjohn Institute has assembled a unique database of cities and their housing markets, which traces the housing supply changes in cities that did, and didn’t change from at-large to single-member district representation.

The key finding: as expected, cities that shifted to single-member districts saw a significant slowing in the rate of the approval of new housing construction, compared to otherwise similar cities that retained their at large systems. Overall, cities that switched to the ward system saw a 21 percent decrease in new housing production after doing so. The decreases were disproportionately concentrated in multifamily housing, where new production declined 38 percent (single family homes were down, too, but only about 11 percent).

Ward-based systems amplify the political power of NIMBY opposition to housing, and thereby limit expansion of the housing supply, and likely drive up rents and home values, which may be a gain for incumbent homeowners, but means less housing affordability for everyone in a city.

Evan Mast, Warding Off Development Local Control, Housing Supply, and NIMBYs, W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, July 10, 2020

In the News

Now is the wrong time for a multi-billion dollar transportation package for the Portland metropolitan area, City Observatory Director Joe Cortright told Willamette Week. The region would be better advised to wait and see how the decline in driving caused by the pandemic (and predicted to continue by auto industry experts) changes the need for transportation investments.