What City Observatory Did This Week

Outdated rules of thumb put a thumb on the scale: Many common land use and transportation planning “rules of thumb” produce harmful results by systematically biasing our built environment toward car dependency. Five problematic heuristics include prioritizing high “level of service” for cars, building unnecessarily wide streets, requiring excessive off-street parking, overestimating car trip generation, and creating hierarchical street networks that increase trip distances.

These outdated practices create inefficient transportation systems hostile to pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users. Reformers are challenging these pseudo-scientific standards, following Donald Shoup’s pioneering critique of parking requirements.

Better alternatives include emphasizing proximity of destinations, designing for slower speeds to improve safety, sharing parking between uses, and prioritizing accessibility over mobility. Rethinking transportation planning requires not just technical changes but reimagining how we conceptualize our cities and transportation systems.

Our updated A to Z list of everything that causes gentrification. Everyone, it seems, has their own pet theories of what causes gentrification. We’ve compiled a long list of oft-blamed mechanisms and tell-tale signs that a neighborhood is gentrifying. In Denver, it was a coffee shop; in Miami it was a park.

Everything from Artists to Zoning gets fingered as a cause of gentrification. Despite the proliferation of explanations, we think that the ultimate underlying cause is a shortage of housing, particularly housing in dense, interesting and attractive urban neighborhoods.

Must Read

Building codes: The Next Frontier in Affordability. For decades, it seems housing affordability advocates have been focused on zoning, and the limits it puts on housing construction. But now reformers are looking under the roof to see what’s driving up costs. And building codes, especially for multi-family construction, make housing more expensive. Writing at Slate, Henry Grabar has an illuminating essay explaining how building codes have been captured by a self-interested group, and have thoroughly–and almost invisibly–dictated urban form and affordability. Grabar quotes Seattle’s Mike Eliason, who’s pointed out the devastating effects of second stairway requirements:

. . . American building codes are unusual in their requirement that even short, small apartment buildings contain two staircases. This fire-safety mandate produces apartment complexes with long central hallways (think: the Overlook Hotel) and apartments with windows on only one side. In his book Building for People, Eliason shows how this rule makes apartment construction on small lots impossible or impossibly expensive, prohibiting many designs that flourish in places like Germany.

A growing band of people and organizations are revisiting the deeply buried assumptions and practices that are codified in building codes, and that among other things, result in a paucity of elevators (which are vastly more expensive in the US than elsewhere), and other features of codes that drive up costs without providing demonstrable safety benefits. It may be time for affordability advocates to look at regulations “inside the box” as well as those outside, like zoning.

Congestion pricing has achieved what abandoned freeway projects failed to do: Actually relieve congestion. Though under a shadow from the Trump Administration, congestion pricing in New York is continuing to prove its value every day, with traffic moving more smoothly, buses arriving sooner, and crashes declining. As Weisbrod points out, congestion pricing is achieving in practice what the failed (and abandoned) freeway projects proposed in the 1950s and 1960s proposed to do. In the sixties, freeway fighters took down the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have been an elevated, 10-lane freeway over Canal Street.

The demise of the Lower Manhattan Expressway has become the stuff of urban legend. The opposition to it was led by Jane Jacobs, and her success in killing the project enhanced her worldwide reputation as the spiritual leader for neighborhood-based planning. Indeed, the iconic New York City neighborhoods of SoHo, TriBeCa, Hudson Square and Nolita would be inconceivable if the 10-lane expressway over Canal Street, with its necessary entrance and exit ramps spreading across the area’s side streets like wings, had been built.

To Robert Moses and other advocates, it was necessary to cut through the city with a meat axe—his actual words—to resolve congestion. But congestion pricing has achieved far better results, far faster, and without ravaging the fabric of some of the nation’s most valuable and vibrant neighborhoods. Pricing finally achieves what Jacobs and other reformers sought half a century ago: reclaiming city streets from domination by cars.

Induced travel trumps wider roads and autonomous vehicles. Time and again, engineers have peddled wider roads and self-driving vehicles as solutions to urban traffic problems. In reality, they’re both never going to solve traffic congestion, and are actually almost certain to make it worse. Anything that makes driving easier, cheaper and more convenient simply leads to more driving–and more auto-dependent land use patterns. Two articles this week remind us of these basic facts. The Scientific American has a nice, non-technical summary of the science of induced travel.

In a similar vein, writing at The Verge, David Zipper reminds us of the 150-year old Jevons Paradox, which pointed out that making some thing cheaper (originally coal) led to dramatically more coal-burning (and pollution). The same applies to self-driving vehicles: the more we lessen the “work” associated with operating a car, the more likely people are to take more and longer trips.

The societal impact of self-driving cars looks even worse when considering second-order effects related to land use. Just as the ascent of car ownership fueled suburbanization in the 20th century, AVs could lead people to relocate to larger, less energy-efficient homes on the urban fringe, where car trips — now more tolerable — are longer.

And critically, the second-order effects of cheaper/easier travel show up in the landscape—development becomes more scattered, and by definition even more car-dependent. Neither wider roads nor self-driving cars will alleviate congestion, and they’ll make our pollution, climate, and equity problems worse.

New Knowledge

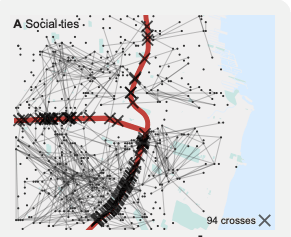

How highways dissolve social ties. It is well known that urban highways were located to disrupt or destroy high poverty and minority neighborhoods, and that highways are formidable barriers to routine urban interaction. A new paper uses data on social media connections to show how highways are barriers to social interaction even today. The study maps the frequency of connections between people using data from Twitter (X). In general, you are more likely to have more contacts nearby, but the data show that an intervening highway is likely to significantly decrease the likelihood of connections. The study computes a “barrier score” for each of the 50 largest cities in the US by estimating how many more social connections one would expect in the absence of highways for a given geography. This “barrier score” is positive for all large cities, meaning the presence of highways leads to less social interaction than one would expect given the overall relationship between space and connections.

The following map illustrates the methodology used. Dots represent the locations of twitter users, lines show connections between users and “x” marks show where connections cross major highways. The modeling approach uses overall data on the spatial characteristics of connections to estimate how many connections would cross the highway location if the highway weren’t there. The difference between the two estimates represents the “barrier” effect of the highway.

This research confirms the intuition that urban highways act as significant barriers to social interaction.

. . . by going beyond demographic approaches, observing social ties explicitly, we have shown that there is a quantifiable association between urban highways and reduced levels of social connectivity, especially at short distances. Our analysis adds a highly granular perspective to former work, corroborating and quantifying the intuition that urban highways are indeed barriers to social ties.

Interestingly, highways are more of a barrier in some cities than in others. The authors estimate that highways are about five times as disruptive to social connections in Milwaukee, Cleveland and Orlando, than they are in New York, San Francisco and Portland.

L.M. Aiello, A. Vybornova, S. Juhász, M. Szell, & E. Bokányi, Urban highways are barriers to social ties, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122 (10) e2408937122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2408937122 (2025).

Ungated pre-publication version available here: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.11596

In the news

In an article entitled “Growing Community Together” in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, Seth Kaplan quoted out City Report, “Lost in Place,” which charted change over four decades in the nation’s highest poverty neighborhoods.