At City Observatory, we’ve been bullish on cities. There’s a strong economic case to be made that successful cities play an essential role in driving national economic prosperity. As we increasingly become a knowledge-driven economy, it turns out that cities are very good at creating the new ideas of all kinds that propel economic progress.

But cities aren’t simply economic machines. Nor are they merely large and efficient collections of buildings, pipes, wires, asphalt and concrete. Cities are importantly a collective social endeavor, what Ed Glaeser calls mankind’s greatest invention. It is the opportunity for interaction with others in cities that is their special power and attraction. Some of those interactions are purely economic, but they are deeply embedded in a much wider set of connections and relationships.

Despite all the strength and energy of cities today, there’s growing evidence that the web of social connections that ties cities together, and that underpins much of their economic importance, is coming apart at the seams. For decades cities have been pulling apart: sprawl has moved us physically further from one another, and within metropolitan areas, our neighborhoods have become more segregated by income.

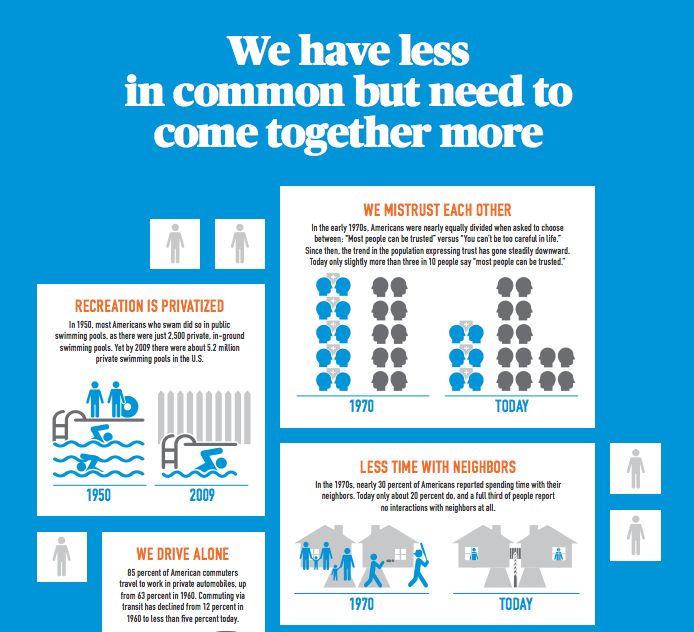

As we pointed out in our CityReport, Less in Common, the shared opportunities and spaces that let Americans of all different backgrounds easily interact with one another have been steadily eroded. We spend more time alone, we socialize with others less, we’re segregated from one another by income, and we generally spend less time in public or in the company of those who are different from us.

Click to see the full infographic.

These trends are mirrored in how we get around, relying more and more on cars cars as a mode of transportation, replacing walking and public transit—modes in which, outside a sealed, private machine, you might actually interact with neighbors or others. In fact, while about 30 percent of Americans reported spending time with their neighbors in 1970, that number was down to about 20 percent today.

This privatizing of our once public lives has also manifested itself in further segregation of neighborhoods by economic status, a trend that has been well documented, and which we have explored at length at City Observatory. Rich and poor Americans have become more spatially divided as we sort into high income and low income neighborhoods. While only 15 percent of Americans lived in rich or poor neighborhoods in 1970, by 2012, that figure was up to 34 percent.

The good news is that there’s a growing recognition of this challenge, and many people and communities are actively looking for ways to rekindle public life. There’s some compelling evidence that the move back to cities is propelled, at least in part, by a hunger for greater opportunities to interact with one another, to—as our friend Carol Coletta puts it—“to live life in public.” This shows up in the growing popularity of “third places”—coffee shops, bars, farmers markets, and other settings where people gather away from home and work.

Its exciting that Knight Foundation and four other foundations have launched their new initiative “Reimagining the Civic Commons.” Over the next five years, these foundations will fund a $40 million grant program to promote innovative projects in five cities: Akron, Chicago, Detroit, Memphis and Philadelphia. The project aims to fund a series of experiments that consider how we might better use a range of public spaces–parks, libraries, and even sidewalks–to foster greater civic engagement. This could turn out to be a vital bit of public-minded venture capital that can help further illustrate—and develop—the vital role that public spaces play in underpinning a successful city.

Fundamentally, this strategy makes sense because of the strong interdependence of the social and economic network effects in cities. Economists portray city economies as being driven by agglomeration effects–the increased intensity and productivity that occurs when large numbers of people can interact (especially when they have diverse knowledge and backgrounds). As Jane Jacobs argued, diverse, well-connected cities produce the “new work” that propels economic progress. But this diversity and connectedness pays dividends in the form of widely shared opportunity. Raj Chetty and his colleagues have shown that cities with lower levels of racial and economic segregation–where its easier for people of different backgrounds to connect–have higher levels of intergenerational mobility, especially for children of low income families.

At their root, as Ed Glaeser has argued, cities are about the absence of distance between people, and that’s not simply physical distance, but social distance as well. Having a civic realm that works well, where people from throughout the city can easily interact is not a mere public amenity, but a vital component of a successful city.