Today we’re publishing an edited version of a speech given by Carol Coletta, VP of Community and National Initiatives at the Knight Foundation, last month in Portland, OR.

Informed and engaged communities are fundamental to a strong democracy. But many of the signs of those communities are not encouraging:

Newspaper readership has plummeted in recent years. It is a particular problem with local papers. More depressing, no one believes there is yet a business model that will support robust local reporting.

Distrust among Americans is increasing. The share of the population that believes “most people can be trusted” has fallen from a majority in the 1970s, to about one-third today.

Economic segregation has gone up while middle-income neighborhoods decline. Between 1970 and 2009 the proportion of families living either in predominantly poor or predominantly affluent neighborhoods doubled from 15 percent to 33 percent.

Politically, we have sorted ourselves into like-minded geographies. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of consistent conservatives and about half (49 percent) of consistent liberals say most of their close friends share their political views.

Portland State’s own Phil Keisling and Jason Jurjevich looked at voting behavior in local elections for Knight and found that turnout in most cities is abysmally low—typically hovering around 20 percent.

They also found that the age of those who do cast ballots was anywhere from 13 to 17 years higher than the citywide median age of the adult population. In other words, as Jason put it, “18-34 year-olds are almost entirely abdicating to their grandparents’ generation the key decision of who should actually govern them.”

Phil and Jason also found many “voting deserts” in cities—places where the percentage of people voting is half or less than the already-terrible overall rates—as low as half a percent! It’s tough to have informed and engaged communities when the trends are working so powerfully against them. On the other hand, there are a few hopeful signs.

As cities cut staff and services to parks and recreation, libraries, and public works in recent years, frustrated citizens have begun taking matters into their own hands. Do-it-yourself efforts to improve cities—sometimes known as “tactical urbanism”—continue to heat up, fueled by the massive move of young adults to core cities.

And while Millennials may not be reading newspapers, they lead the country in the civic use of social media. Pew found that half of 18-to-29 year olds decide to learn more about political or social issues because of what they read on social networking sites. Fifty-seven percent engage in political activity on social networking sites and nowhere else.

If only they could be convinced to vote.

Voting isn’t the only means of civic participation, of course. But a high and sustained voter turnout rate is the best single measure of whether all the other things we are doing to promote engagement are working—and that’s why we make increased local voter turnout the North Star for our efforts.

But here’s a conundrum: Knight, as a foundation, doesn’t support “get out of the vote” efforts. We don’t support voter registration. We don’t support efforts to overturn voter suppression.

So what’s left that looks promising?

To get the answer, we turned to Portland. Last year, thanks to my friend and colleague Ethan Seltzer, I had the opportunity to interview the founders of modern day Portland. They told me how they reclaimed power from the small group of elected elites who used to wield their influence from the basement of a downtown hotel.

They decided that if they were to engage Portlanders in the civic life of their community, they had to be convinced to “live life in public.” In other words, they had to be lured from the comfort and privacy of their living rooms and backyards and share public life in the company of strangers.

At the time, there were, they told us, a lot of impediments to doing that. There was, for instance, a prohibition against playing music in the park. Sidewalk cafes were illegal.

So they set out to eliminate as many of the things that discouraged public life as they could. And today, you have a wonderfully rich public realm and many signs of robust public life. Like the founders of modern day Portland, we believe that public life—or “living life in public,” as they put it—is critical to civic engagement.

And yet, many of our so-called “engagement processes” that are codified into law are clearly deficient. There is the requisite three-minute public comment period in every public meeting. Architects and planners must have engagement “specialists” on their teams. App developers have had a field day with their attempts to induce civic engagement via smart phones (many of them supported by Knight funding).

But our efforts are failing miserably. Just look at the rate of voting in local elections. Most Millennials don’t see voting in local elections as a way to express their values, nor do they see local government as a way to get things done. And apparently, a lot of other Americans agree.

As long as opportunities for civic engagement are episodic, tucked away, or on a schedule, I’m not sure we will ever have the broad engagement we need to make our communities successful. We don’t need the occasional well-attended community meeting with 100 people in the audience. We need thousands of people engaged every day in the civic life of their city. And we believe that the places we inhabit everyday can be a far more powerful way to stimulate a culture of engagement than any process or any app.

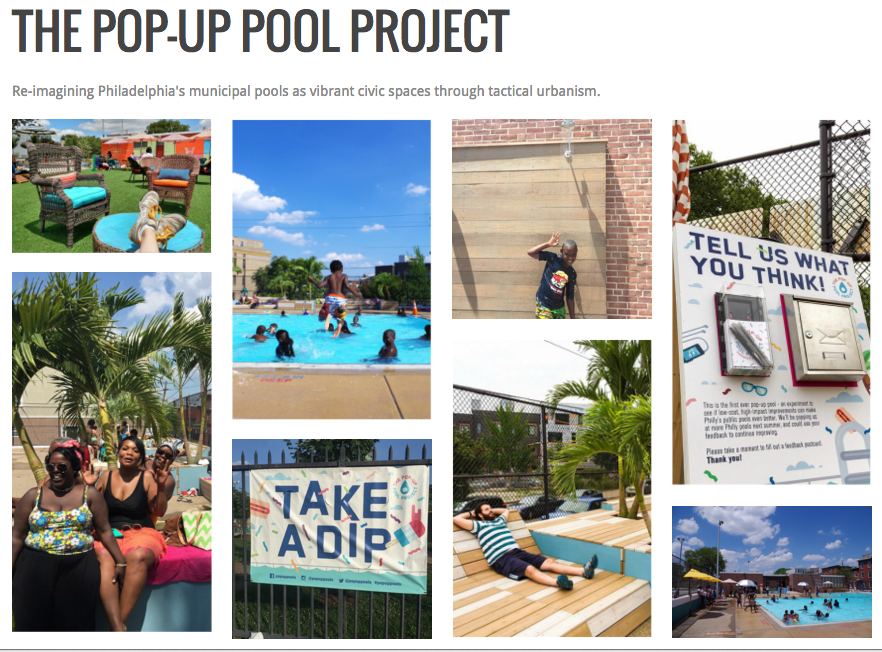

I want to offer up one very humble example of what’s possible. It’s called the Pop-up Pool in Philadelphia’s Francisville neighborhood, between a very poor neighborhood and one that is seeing a lot of new investment. It is the product of Ben Bryant, who submitted his idea to the Knight Cities Challenge.

Public pools, as you may know, have tortured racial histories; and as private pools have proliferated, support for public pools has waned, leaving a customer base consisting of those with no other options—in Philadelphia, that means usually poor, usually black, and in the case of Philly’s pools, usually under 18.

Ben took a look at Philly’s pools and saw the potential for a much more dynamic neighborhood asset, one that could attract people from the two very different neighborhoods that bordered it.

How to do that? Pretty simple.

- Add seating where there was none.

- Add a few palm trees to amp up the emotional resonance of the pool as a stay-cation.

- Add water Zumba classes that everyone could enjoy while looking slightly dorky doing;

- Change the rules so moms could enter the pool with street clothes on vs. a bathing suit.

- Promote it daily on social media in ways the city never would.

It was an immediate hit. The pool suffered no loss of existing patrons, but it gained new popularity with residents who discovered the pool for the first time. People of different economic status, different ages, and groups of singles along with parents and children were happily sharing the pool together.

It took less than a week for the City to announce that it planned to convert all of its pools to the pop-up pool model.

Writing in The New Yorker last month, Adam Gopnik described the mixing we need this way: “Cities…shine by bringing like-minded people in from the hinterland (gays, geeks, Jews, artists, bohemians), but they thrive by asking unlike-minded people to live together in the enveloping metropolis…. While the clumping is fun, the coexistence is the greater social miracle.”

If we can crack that one, we can unlock enormous opportunity for Americans.

The future of a city is not made with a few broad strokes by a few key people. The future is made by thousands of people making small decisions every day about what they believe about the future and their role in it. By building up the civic commons—parks, recreation centers, libraries, cultural centers—to support the active sharing of public spaces and activities by a wide mix of people of different economic statuses, different ages, we can encourage people to make those decisions in a way that builds more informed, engaged communities, and a stronger democracy.