Why Portland’s freeway fight is so important to the future of cities everywhere

The plan to widen the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway in Portland, at a cost of $500 million, is a tragic error for one city, and an object lesson to others. A wider freeway will induce more traffic and pollution (and ironically, worsen traffic congestion), runs directly counter to the city and state’s goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, does nothing to improve safety, especially for those walking or biking, and disproportionately benefits higher income commuters from outside the city, while imposing social and environmental costs primarily on lower income households and people of color.

There’s a lot we have to do to meet the growing demand for urban living. The first rule, as in medicine, is to do no harm. In Portland, and in cities around the nation, building freeways has been consistently shown to devastate urban neighborhoods, and only exacerbate traffic congestion and car dependence. This is a signal issue, around which much of of possibility of crafting better, more sustainable and more inclusive cities revolves. That’s why we’re spending time exploring this issue in detail here. The battle over this freeway widening project is increasingly drawing national attention, and the leading experts are warning Portland its in danger of making a terrible mistake.

This is City Observatory’s guide to the public policy case against the proposed I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway Widening Project

Traffic congestion will worsen, thanks to induced demand

Widening the freeway won’t solve traffic congestion. More highway capacity generates more traffic–the phenomenon of induced demand is so well documented that it’s now called “The fundamental law of traffic congestion.” Added capacity encourages more people to drive, and in dense urban environments, there’s plenty of “latent demand” that almost immediately fills added lanes as soon as they’re built. Houston widened its Katy Freeway to 23 lanes, and it’s now even more congested and slower moving than before. Even PBOT and ODOT officials acknowledge that widening I-5 won’t reduce daily traffic congestion.

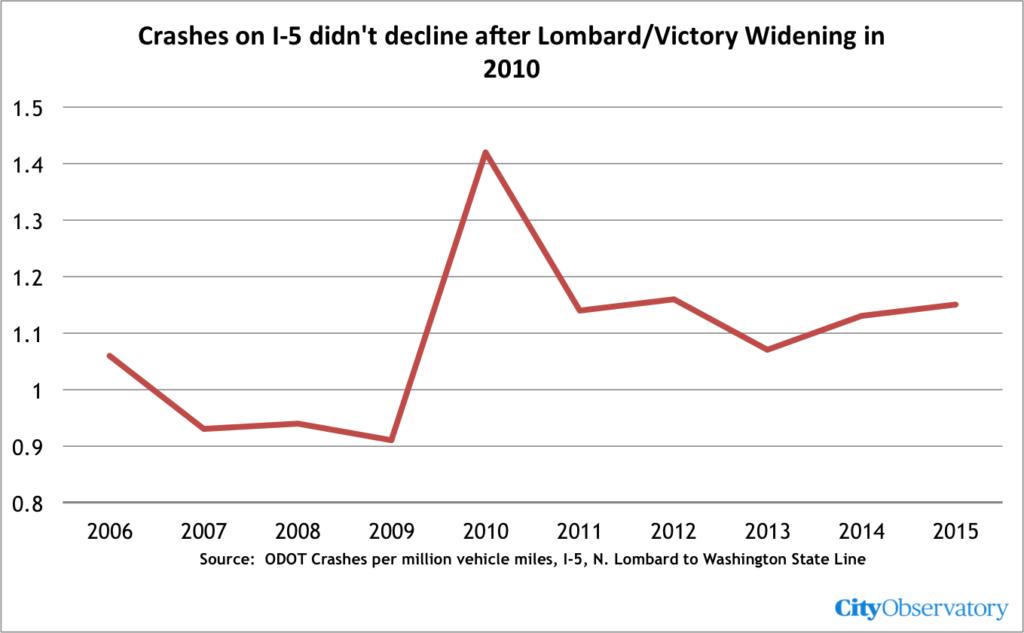

A wider freeway won’t reduce crashes that produce “non-recurring” congestion. Because they know they can’t reduce daily congestion, city and state engineers instead make a different claim: that more lanes and wider shoulders will reduce occasional congestion from crashes. But they don’t actually have evidence for that; instead the claim is just based on engineering “rules of thumb.” And our actual experience on this freeway, with the same drivers, has been just the opposite: After ODOT widened I-5 between Lombard and Victory Blvd. in 2010, crashes went up, not down. It’s not surprising: Metro’s State of Safety report shows that wider roads tend to have higher crash rates. If crashes don’t decline, ODOT can’t claim to reduce traffic congestion.

Wider roads will likely make congestion worse. There’s good evidence that funnelling more traffic onto the region’s roads will actually cause congestion to get worse. After ODOT widened I-5 north of Lombard, and expanded ramps onto the freeway, traffic congestion became worse, as more cars were funnelled even more rapidly into bottlenecks, causing the freeway to lose capacity. Consequently, the Interstate 5 bridge now carries about 10 percent fewer cars in the afternoon peak hour than it did ten years ago.

Climate change: greenhouse gas emissions will increase

The threat of climate change is real and serious, and Oregon is failing in its legally adopted goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 20 percent of 1990 levels by 2040, almost entirely due to an increase in driving in the past few years, according to the latest report of the Oregon Global Warming Commission.

The University of California, Davis’s induced travel calculator suggests that widening the I-5 freeway at the Rose Quarter will generate an additional 10 to 17 million miles of vehicle travel per year, adding to hundreds of tons per year to Portland area greenhouse gas emissions.

Widening freeways runs directly counter to the need to take decisive action to deal with climate change. The evidence from last summer’s smokey skies to the latest dire report from the International Panel on Climate Change show we’ve put off action too long. And in Oregon, the latest state report tells us we’re losing ground in our stated objective to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, almost entirely because we’re driving more. More freeway capacity will produce more driving. ODOT is claiming that somehow by reducing congestion (which they won’t do anyhow), that they’ll reduce pollution and greenhouse gases associated with idling. That folk myth has been thoroughly debunked by the transportation experts at Portland State: emissions from added car travel more than offset lower pollution for idling.

ODOT has previously lied about the the carbon emissions of its activities to promote its objectives. In 2015, the Director of ODOT admitted to the Oregon Legislature that his agency had grossly overstated the carbon emission reductions that could be expected from so-called “operational improvements” to state freeways. This led to the collapse of transportation legislation, which was predicated on carbon reductions.

There is no evidence that operational improvements, like variable speed signs, which are the centerpiece of ODOT’s climate strategy, have any meaningful effect on carbon emissions. Independent studies showed that implementation of variable speed signs on Highway 217 were accompanied by an increase in crashes, and not a reduction; there’s no evidence they improved congestion.

Congestion pricing would solve Rose Quarter congestion more quickly and cheaply

The only effective means of reducing traffic congestion is road pricing. Two years ago, the Oregon Legislature enacted HB 2017, directing ODOT to pursue congestion pricing on I-5 and I-205. ODOT’s own studies show that congestion pricing would dramatically reduce congestion in the Rose Quarter area, and improve transit operations and freight mobility, while increasing freeway throughput. ODOT has completely omitted any mention of congestion pricing in the Environmental Assessment. Leaving out this demonstrably superior alternative is a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act.

Widening the freeway won’t improve safety

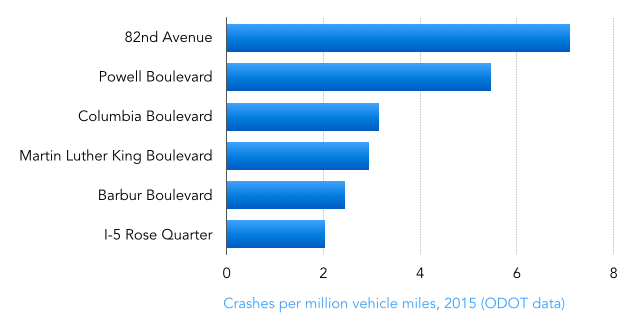

The Oregon Department of Transportation falsely claims that the Rose Quarter is the highest crash location in the state. In fact, many other ODOT operated roadways in the Portland area have far higher crash rates than the Rose Quarter.

Freeways are among the safest roads in the Portland metropolitan area; the typical multi-lane urban arterial street in Portland has a crash rate five times higher than urban freeways. Virtually none of the crashes on I-5 at the Rose Quarter involve serious injuries or fatalities. Willamette Week debunked ODOT’s safety claims:.

There’s is no evidence that widening I-5 at the Rose Quarter would reduce crashes. When ODOT widened Interstate 5 just north of the project area (a roadway that carries the same vehicles that travel through the Rose Quarter) crash rates did not decline, in fact they increased. Similarly, when ODOT increased capacity at the Woodburn intersection on I-5, crash rates also did not decline; that intersection had two serious crashes in the space of ten days in February 2019.

Freeway widening will worsen pollution

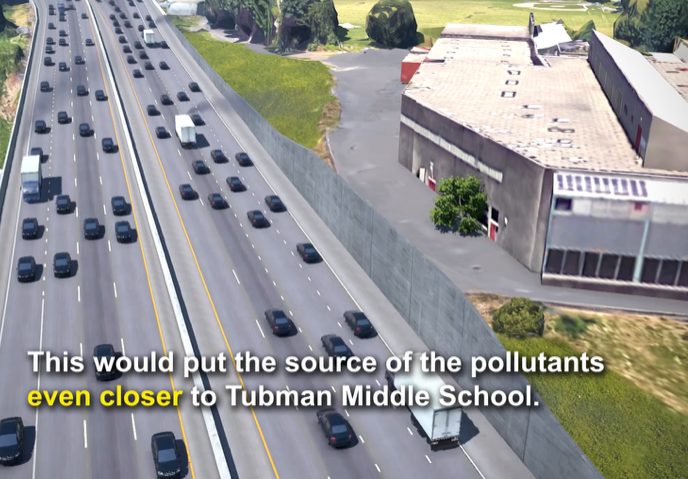

Increased traffic and air pollution will most severely affect students at Tubman middle school–the project would widen the freeway onto land now occupied by the school. Construction of the freeway will require excavating land at the school site and bring the freeway within feet of the school building.

Scientists at Portland State University who studied air quality at the Tubman site recommended that students not engage in outdoor activities to avoid exposure to air pollution from the freeway. The school district spent $12 million on on environmental protection for Tubman, mostly for special air filtration equipment to make air inside classrooms safe for students to breathe. It’s monumentally unfair that students should bear the dual costs of breathing polluted air, and have their scarce educational dollars used to pay for air filters, while roads are used by high income commuters, who pay nothing towards these costs.

Freeway widening is inequitable

Widening freeways generally privileges higher income people, while doing nothing, or actually worsening travel and the environment for lower income people. There are huge disparities in the income, race and ethnicity of the project’s primary beneficiaries (peak hour, solo car commuters) and local area residents, including those who walk, bike and take transit, and households who don’t own cars.

- Peak hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon have a median household income of $82,500, 50 percent greater than the transit, bike and walk commuters living in North and Northeast Portland ($53,900), and more than three times greater than carless households in North and Northeast Portland (23,500).

- Two in five (40 percent) of peak hour drive alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon have a median household income of more than $100,000.

- Three-quarters of peak hour, drive-alone commuters from Clark County to Oregon are white, Non-Hispanic. Two-thirds of Tubman Middle School Students are persons of color (including multi-racial).

- Nearly half of all Tubman Middle School Students qualify for free and reduced price meals.

- A majority of those who live in the project area (Census Tract 23.03), commute to work by transit, bike or walking.

Freeway widening doesn’t repair the Albina Neighborhood

Widening the freeway does nothing to fix the decades long scar ODOT inflicted on the neighborhood in the 1960s. ODOT demolished and never replaced over 300 homes in the Interstate 5 freeway right of way. Truly mitigating that damage would require providing $140 million to build new housing to replace that lost–not making the freeway even wider.

The freeway widening–coupled with other urban renewal projects–triggered neighborhood decline that led to the displacement of 60 percent of the neighborhood’s population (more than 1,700 persons). The neighborhood’s black population declined. Freeways and the traffic they generate are intrinsically inimical to healthy urban spaces.

The covers proposed for the freeway are needed just to facilitate construction (allowing traffic to be re-routed when existing overpasses are demolished). Surrounded by high volume, fast moving auto-dominated arterials, they’re genuinely un-pleasant spaces for humans. They’re badly fragmented and poorly located to provide meaningful public space. ODOT has no plans or budget to build them strong enough to support buildings (which would likely be cost-prohibitive while spanning a widened active freeway right-of-way).

Bicycle and Pedestrian access is impaired by freeway widening

The Rose Quarter Freeway widening project would demolish the current Flint Avenue Crossing over Interstate 5. Flint Avenue is a low-speed, low volume neighborhood street that provides a safe, limited grade route between Northeast Portland and the Rose Quarter and Broadway Bridge.

The freeway widening project would replace the current Flint Avenue crossing with steep and indirect bike-pedestrian bridges on Hancock and Clackamas Streets. It is not clear from existing designs that the grade of these two structures would be compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. The City’s own Pedestrian Advisory Committee has prepared a devastating critique of the project’s impacts on neighborhood walkability.

The project would build a diverging diamond interchange along Williams Avenue, in which car traffic would be placed on a two-way street with cars running in the left lanes–the opposite of every other street in the city. This would create a hostile environment for bicyclists and pedestrians. In addition, at the intersections of Broadway, Weidler, Vancouver and Williams, ODOT would increase the radius of curvature, accelerating car traffic across crosswalks in this area. The project’s renderings paint a highly distorted picture of the project, showing five times as many pedestrians and forty time fewer cars than actually use city streets.

Cost overruns

ODOT has routinely experienced cost overruns of 200% or more on its major projects. It’s largest highway project, a five-mile widening of US 20 between Newport and Corvallis wen more than 300% over budget, rising from $110 million to more than $360 million. It’s Grand Avenue Viaduct project in Portland went 300% over budget, costing $98 million rather than $31 million. The Woodburn Interchange on I-5 ballooned from $25 million to $70 million.

Editors Note: The commentary was updated on March 26th to reflect additional information published on City Observatory.