Portland is a bellwether for transportation policy; is it going to take a giant step backward?

Last month, the Oregon Legislature passed a $5.3 billion transportation funding bill. A central piece of this legislation is advancing three projects that would widen Portland area highways. HB 2017A makes initial allocations of funding to start (but not necessarily enough funding to actually complete) the addition of lanes on Interstate 5 near downtown Portland, to Interstate 205 in the region’s Southern suburbs, and State Highway 217 in the western suburbs. Each of these projects is being sold as “bottleneck” buster, and assumes that just a little bit for freeway capacity will somehow magically resolve daily traffic congestion. After decades of progressive leadership in transportation policy, “Portland freeway widening” has a certain “man-bites-dog” quality as a story, but we think there’s something more here.

Regular readers of City Observatory might well ask why we’re spending so much time talking about a proposal to spend upwards of a billion dollars widening three Portland-area freeways. And it’s perfectly fair for them to think that we’re being a bit parochial focusing on these projects (City Observatory is based in Portland). So it’s true that we have more than an academic interest in the proposed projects.

But we think something more is at stake, and that Portland represents a kind of bellwether for moving US transportation policy forward.

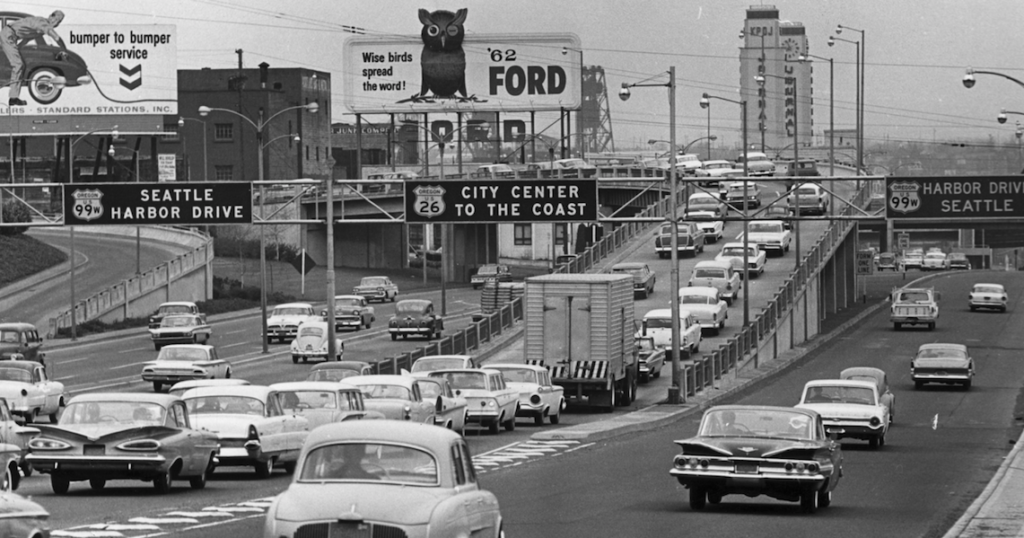

Back in the 1970s, Portland and Oregon were national leaders in a broad range of environmental policies, from cleaning up badly polluted local rivers, to making sure the state’s beaches remained in public ownership, to implementing the nation’s first beverage container deposit law, to requiring statewide land use planing including drawing urban growth boundaries around each of the cities in the state. In many ways the signature items in this environmental litany were the decisions to demolish one freeway (downtown Portland’s Harbor Drive) and to cancel another (the Mt. Hood Freeway). These decisions, and a range of supporting policies that unfolded in their wake (building a regional light rail system, greatly expanding biking, bringing back the streetcar) made Portland an important leader in using a different approach to transportation to build a great urban place.

Looking back, what is it we knew 40 years ago, that we no longer know today? At the dawn of the environmental movement, Portland was willing to take bold steps that not only challenged the conventional wisdom, but pushed the boundaries of policy with a steady stream of civic innovation.

We now know that climate change disruption is ongoing, and unless we take immediate and decisive action to reduce carbon emissions, we are likely to permanently damage the planet.

Looking forward, with the days of the internal combustion engine numbered, with autonomous vehicles moving steadily closer to market, why are we intent on putting a huge chunk of scarce public resources into a minor, out-dated and ineffective part of the transportation system?

The proponents of the project are trotting out an impressive array of myths.

- They argue additional capacity is needed to reduce congestion. It’s now settled fact that additional un-priced roadway capacity in urban areas simply generates more traffic, congestion and pollution.

- They argue that idling in traffic contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Studies by engineers at Portland State University show this is a myth, and that highway expansions lead to more greenhouse gases.

- They play the safety card, talking about crashes. But freeways are five times safer than city streets according to the region’s transportation planning agency, Metro. And congested freeways actually have fewer serious crashes than fast-moving ones.

And this project comes forward at exactly the time the Oregon Legislature is being told by its official Global Warming Commission that the state is going to fail to meet its legally adopted goal for reducing greenhouse gas emissions because of an increase in driving in the state.

There’s one glimmer of hope on the horizon. As part of its newly passed transportation legislation, Oregon has directed its Department of Transportation to seek federal permission to toll the urban portions on Interstate 5 and Interstate 205. Peak hour real-time tolling of freeways could reduce congestion and greenhouse gases without expanding capacity at all. If it moves ahead with a comprehensive, state-of-the-art tolling system for freeways, Portland could again put itself in the ranks of innovative cities when it comes to transportation.

So in the months ahead, dear readers, we hope you’ll bear with us as we turn a careful eye to Portland’s freeway widening proposals. We think there’s a lot going on here that’s of more than local interest.

If you want to get a flavor for how this issue is being discussed locally, here’s City Observatory’s Joe Cortright discussing the proposal to widen Portland area freeways with State Senator Lee Beyer, the author of the legislation, on Oregon Public Broadcasting’s “Think Out Loud.”