The Interstate Bridge Project has released—after years of delay—computer graphic renderings showing possible designs for a new I-5 bridge between Vancouver and Portland. But what they show is a project in real trouble. And they also conceal significant flaws, including a likely violation of the National Environmental Policy Act. Here’s what they really show:

- IBR is on the verge of junking the “double-decker” design its pursued for years.

- It is reviving a single decker design that will be 100 feet wider than the “locally preferred alternative” it got approved a year ago.

- The single deck design is an admission that critics were right about the IBR design having excessively steep grades.

- The single deck design has significant environmental impacts that haven’t been addressed in the current review process; The two states ruled out a single deck design 15 years ago because it had greater impacts on the river and adjacent property.

- IBR’s renderings are carefully edited to conceal the true scale of the bridge, and hide impacts on downtown Vancouver and Hayden Island.

- IBR has blocked public access to the 3D models used to produce these renderings, and refused to produce the “CEVP” document that addressed the problems with the excessive grades due to the double-deck design.

- The fact the IBR is totally changing the bridge design shows there’s no obstacle to making major changes to this project at this point.

The actual appearance of the proposed $7.5 billion Interstate Bridge Replacement project has been a carefully guarded secret. IBR has finally produced renderings of what the bridge might look like, and they conceal more than they reveal. All of the renderings are shown from a distant vantage point—probably a mile or so away from the actual bridge—making it look tiny. And the renderings don’t show how much larger the proposed new bridges are than the existing bridge. The renderings are also carefully crafted so you can’t tell how tall the bridge will be in relation to the buildings in downtown Vancouver (it will be taller than most of them), nor does it show a lengthy elevated viaduct that will tower over most of Hayden Island. What the renderings do show is that IBR is now almost fully committed to a single-level bridge design. Whereas prior renderings never showed a single-level bridge, five of the six designs presented on the IBR website are single-level bridges, and only one is the double-decker design the IBR has been pushing for more than a decade.

And none of these renderings show the actual width of either the single- or double-deck versions. Other ODOT documents—not included with the renderings—show the singe-deck designs will be more than 270 feet wide—nearly as wide as a football field is long. We know that IBR has developed a sophisticated 3D model—a “digital twin” of the project. IBR consultants bragged about the state-of-the-art detail of the model in a presentation to a professional group in Seattle earlier this year, but said they couldn’t share the illustrations, because:

“There is a very detailed 3D model. I was going to try and show it . . . It’s very, very, it’s kept under wraps quite a bit, and I think it’s because of their experience with the first round, trying to tread carefully.”

We filed a public records request with WSDOT and in response, they claimed that the only “model” was a rendering released in January 20, 2022, and that they are ignorant of this work—even though contractor WSP and software provider Bentley prominently tout this “digital twin” work for IBR on their websites. And obviously, IBR had this 3D model in place to produce the renderings it released on May 25. It’s plain that ODOT and WSDOT don’t want people to see what they are planning to build.

Junking the double decker design

What these new renderings signify is that the Oregon and Washington DOTs are junking the double-decker design they’ve been pushing for the Interstate Bridge Replacement for more than a decade, and instead are planning a much wider single-level bridge.

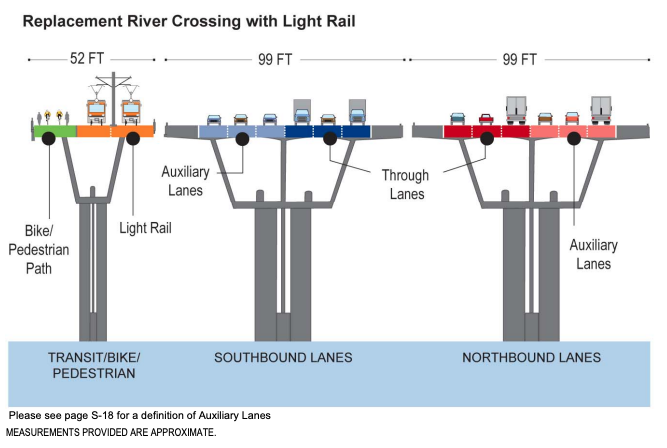

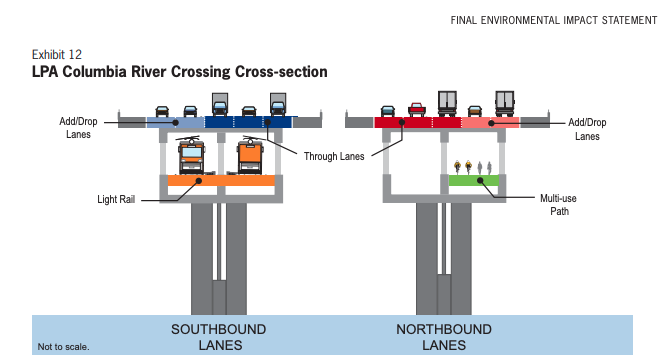

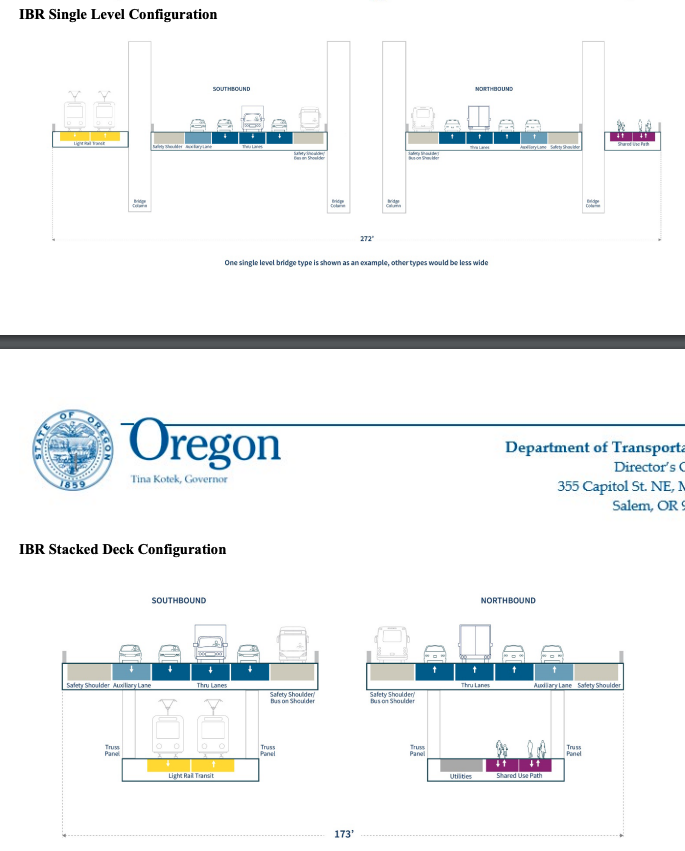

Since 2008, ODOT and WSDOT have only been looking at a pair of double-decker bridges to replace the existing I-5 crossing. Each of these bridges would be about 90 feet wide, with room for six highway lanes on the top deck of each bridge, and provision for light rail, bikes and pedestrians on lower levels.

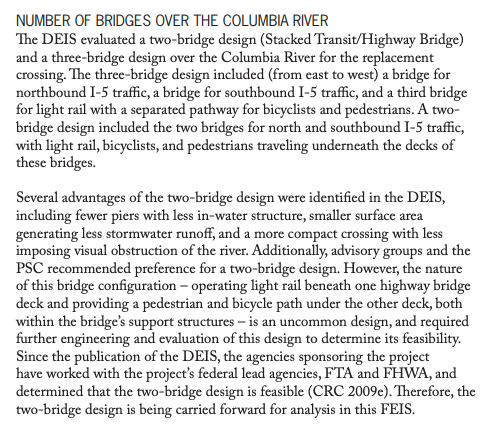

As part of the project’s draft environmental impact statement, the two highway departments considered, and rejected, a single-level design, because it would have had greater impacts on the river (more piers in the river, more cover over the river, and greater visual impacts). Only the double-decker design was advanced to the Final Environmental Impact Statement, adopted in 2011.

Now, suddenly, IBR is pushing a slew of single-level designs. We say “suddenly” because IBR made no mention of a single level option until February of 2023—almost a year after it asked all of its local partners to sign off on a “Modified Locally Preferred Alternative” that consisted solely of the double decker bridge.

As we wrote in February, this sudden change of heart vindicates one of the key criticisms of the IBR design—that its high fixed span necessitates very steep grades, both for the mainline highway section, and especially for the bridge’s off-ramps. The grade for the mainline would be as much as 3.99 percent—well in excess of the DOT’s own guidelines for freeway grades, and among the steepest interstate bridges in the nation. The grades on on- and off-ramps would be even higher, as much as 6-7 percent. Notably, each of the single-level designs allow the roadway to be set much closer to the river, enabling shorter structures and shallower grades.

The key factors increasing the grades of the highway section of the project is the combination of its high river clearance (the IBR design calls for a 116′ navigation clearance underneath the bridge), and the proposed double-decker design (with the top highway deck being elevated about 35 feet above the lower transit/active transportation deck).

A Bridge Too Steep and the Secret CEVP Report

What prompted the sudden inclusion of the single deck design? As we wrote in February, the key intervening event was a project evaluation called the “Cost Estimate Validation Process” or CEVP, which is designed to identify and assess risks to project costs and completion. It seems highly likely that this review identified the steep grades on the bridge and approaches as a cost, schedule and approval risk. That’s almost undoubtedly what prompted the sudden interest in the single-deck design, after years of exclusion. We say “almost undoubtedly” because IBR has refused to release the CEVP analysis. When we first asked, in December 2022 for the CEVP, WSDOT claimed that “no such document exists.” Subsequently it has released only a cursory and uninformative one-page summary of the CEVP, even though it has subsequently reported that the CEVP consisted of creating a “risk register” that identified more than 200 risks.

A QRA [quantitative risk assessment] was performed for the IBR program based on CEVP methodology. The objectives of the QRA were to provide independent review of program cost and schedule estimates and to quantify the uncertainty and risk associated with those estimates. A risk assessment workshop was held October 10 to 14, 2022, and was attended by IBR program team members, partners, and subject matter experts (SMEs) from WSDOT, ODOT, local agency partners, and industry. A risk register was developed for the program; the register identified specific risks (threats and opportunities) to the program cost and schedule. A total of 201 risks were identified, of which 121 were determined to be significant. Risks were characterized and quantified by consensus (i.e., collective professional judgment) of the SMEs assembled for the workshop.

Financial Plan, March 2023, page 4-2 to 4-3,

It’s not unusual for agency’s to make some tweaks to a project once it has gone through the environmental review process, but the usual claim that the DOTs make is that these tweaks are okay as long as they don’t increase the project’s “footprint.” That’s a legally dubious assertion, but, in this case, shifting to a single level bridge actually increases the project’s literal footprint by over 50 percent: According to ODOT’s own estimates, the double-decker bridge design would be about 173 feet wide, while the single-level bridge would be about 272 feet wide.

For four years, the Oregon and Washington highway departments have been pushing a revival of the failed multi-billion dollar I-5 Columbia River Crossing. Their key sales pitch is that the size and design of the project can’t vary in any meaningful way from the project’s decade-old record of decision, for fear of delaying construction or losing federal funding.

Far from being a minor change, this represents the revival of an alternative design that was ruled out more than a decade ago. It also shows that the IBR project is effectively conceding that its critics, who’ve alleged that its double-decker “modified locally preferred alternative” has a serious safety and cost problem due to its excessive grade and elevated off-ramps. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it shows that warnings that major changes couldn’t be made to the project out of a fear of delays were simply baseless manipulation—a familiar highway department tactic.

Resurrecting a discarded 15-year old alternative

When he first revealed that IBR was considering a single level design in February of 2023, IBR administrator Greg Johnson made a point of claiming that the single-level design isn’t “new.” It isn’t, it’s quite old, and to have listened to the Oregon and Washington transportation departments, it’s so old that it’s been dead and buried for almost 15 years.

The last official ODOT and WSDOT document featuring a single level crossing design was nearly 15 years ago: the 2008 Draft Environmental Impact Statement. It proposed two possible designs for replacement bridges for the current I-5, a pair of side-by-side double-decker bridges (which were chosen as the preferred design), and a trio of single-level bridges, as shown here.

The project’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, issued in 2011, abandoned the single-level option, and chose to proceed only with a pair of double-decker bridges (with transit and bike-ped access placed on the lower level of each structure). Also: Notice that the Final Environmental Impacts Statement omitted the notations showing the actual width of the proposed structures—part of an effort to conceal the fact that the bridges would be build wide enough to accommodate 12 full lanes of traffic.

The Final Environmental Impact Statement made a strong series of findings rejecting the single-level three-bridge design, because it would have more in-river impacts, a larger surface area with more runoff, and would have larger visual impact. [CRC FEIS, Page 2-83]

The single-level design is considerably wider than the two-bridge double-decker design, as shown in this 2007 rendering prepared by IBR.

It’s not too late to make fundamental changes to the plan

Greg Johnson has cried “wolf” about making serious changes to the IBR project, even as its budget has ballooned by 54 percent in a little over two years, to a total price tag of as much as $7.5 billion. But this latest—and very late—change to the project design is an indication that it’s not too late to fix the fatal flaws in this project. Right now the fatal flaws revolve around its bloated design and price. The reason the project is so expensive has little to do with the bridge structure itself, but rather the extravagant plans of ODOT and WSDOT to widen I-5 for miles on either side of the Columbia River, and rebuild, at much greater expense than the bridge itself, seven different freeway interchanges. If this were simply a bridge replacement—as its name claims—the project would be vastly simpler, less expensive, and likely not controversial.

For the past four years, IBR has maintained it’s far too late to make any design changes to the IBR project. Ever since he took the job of IBR administrator Greg Johnson has been warning elected officials not to make any significant changes to the project design included in the 2011 FEIS for fear of delaying it further. An immersed tunnel? More consideration for climate? A lift-span? A narrower freeway? None of these can even be studied, or advanced into the environmental review process, for fear that it will cause some additional delay.

But now, what about that inviolable “Modified Locally Preferred Alternative” that you couldn’t touch in any way without endangering the project’s schedule and jeopardizing federal funding? Well, IBR staff have unilaterally decided it won’t actually work, and their pushing ahead with an entirely new and much wider design, any trying to shoehorn it into the federal environmental review process without honestly disclosing the major changes they’ve made.

More than six months after theoretically getting buy-off from all of the project’s eight partners for this untouchable design, and spending tens of millions of dollars defining the “modified locally preferred alternative,” Johnson has suddenly decided that he can unilaterally inject back into the discussion an alternative that the project ruled out more than a decade ago. And make no mistake, changing from double-decker bridges to a single level crossing has significant impacts. It almost certainly means more piers in the Columbia River, and more real estate disruption, particularly on the steadily redeveloping Vancouver waterfront.

For the record this isn’t the first, or even the second, time the engineers at ODOT and WSDOT have screwed up the design of the proposed river crossing. In 2010, an Independent Review Panel appointed by Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski and Washington Governor Chris Gregoire found that the “open web” design the agencies proposed was “unbuildable.” It was replaced by the double-decker truss. And then, in 2011, the bridge had to be re-designed again to achieve a river clearance of 116 feet, because the two highway departments couldn’t bludgeon the Coast Guard into accepting their preferred 95 foot clearance. Both these engineering errors delayed the project and raised its cost—something you’ll never hear ODOT and WSDOT admit.

Why now?

The problems with the bridge grade were first identified more than a decade ago, when the Coast Guard objections let ODOT and WSDOT to hastily redesign the Columbia River Crossing to provide a 116-foot navigation clearance (21 feet higher than what the two highway agencies were then planning). ODOT and WSDOT never resolved the questions that were raised about the project’s excessive grade, particularly concerns that steep bridge grades would cause large trucks to slow and impede traffic flow. Following Johnson’s insistent demand that no changes be made to the project defined in the Columbia River Crossing FEIS, IBR has stuck to the steep, double-deck design, never questioning the grade.

But late last year, IBR has had to produce a new cost estimate. Embarrassingly, the cost of the IBR project has ballooned by 54 percent to nearly $7.5 billion. To deflect criticism about higher costs, IBR officials testified in December that the project was also subjected to a “Cost Estimate Validation Process,” or CEVP, which the state DOTs advertised as a sure-fire cure for future cost escalation. As we pointed out at City Observatory, no documentation exists for that claimed CEVP. The Washington Department of Transportation responded to a public records request for copies of the CEVP by saying “no documents exist.” Because the agencies have shrouded this process in secrecy we can’t say for sure, but it seems likely that a CEVP meeting likely identified the bridge grade, and expense of elevated interchanges as major cost, schedule and design risks to the project. That would explain why, more than six months after locking down a double-decker “modified locally preferred alternative,” that Johnson and the IBR team are suddenly reviving the discarded single-level bridge plan.

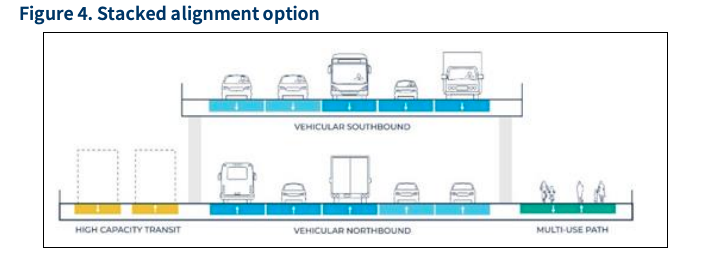

IBR’s Stacked Highway Bridge Alternative (2021)

For reference, we’re providing details of the alternative designs that have been considered by the IBR in the past decade. As noted above, the last time any of the project’s documents mentioned a single-level crossing was in the 2008 Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Most recently, in October 2021, when it last listed the alternative bridge designs it was studying, IBR made absolutely no mention of a “single-level bridge”. In fact, the only alternative design they showed was pretty much the opposite: a single and larger stacked bridge, with highway lanes on the upper and lower levels of the double-decker bridge, and with transit and bike-pedestrian routes cantilevered on the sides of the lower level of the double decker. And now, when it comes time to produce actual renderings, the single bridge stacked alignment has simply disappeared without a trace.