Does geographic rating of car insurance amount to 21st Century redlining?

Car insurance rates vary more based on who your neighbors are than on your driving record

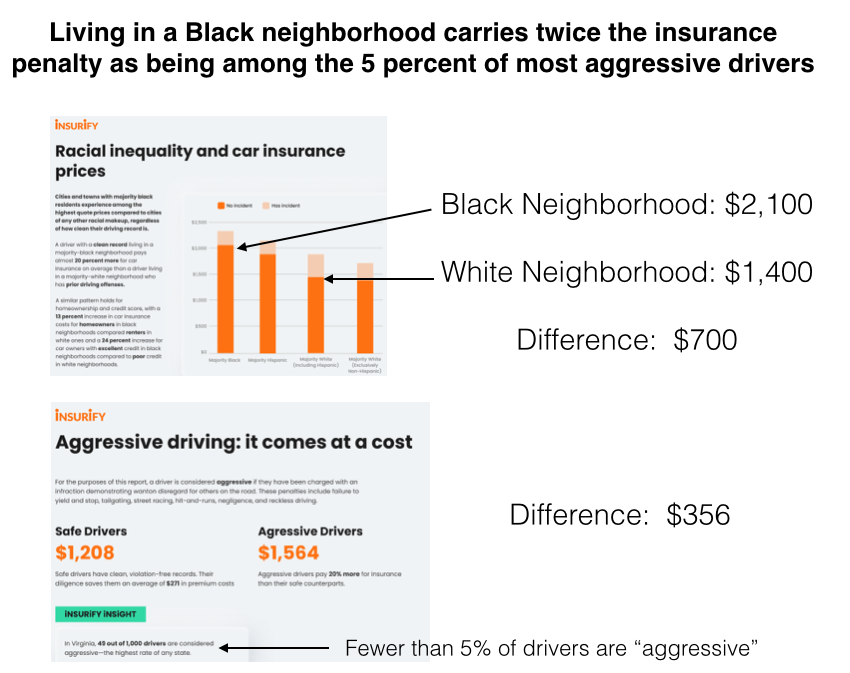

The premium penalty for living in a Black neighborhood is twice as large as for being an aggressive driver.

States should ban using small geographies, like zip codes, to set insurance rates.

In the the past several months, there’s been increased attention paid to whether our transportation system is equitable. Public policy debates have hinged on whether or not building bike lanes is equitable, and whether major regional transportation packages benefit disadvantaged communities. Huge and hidden subsidies that chiefly benefit higher income households, like nearly universal free parking, seldom get questioned from an equity perspective.

As we’ve stressed, its impossible to understand the equity aspects of transportation without looking comprehensively at the whole system. And one important aspect of transportation is the nearly universal requirement that everyone who drives a car purchase car insurance. After depreciation, insurance, along with fuel, is the largest cost of operating a car. (If your vehicle gets 20 miles per gallon and you drive 12,000 miles per year, you buy about 600 gallons of gas; at current prices, of about $2.12 per gallon, you spend roughly $1,272 on fuel, which is very much in the same ballpark as the typical auto insurance premium ($1,463) reported by Insurify.

But are car insurance premiums fair and equitable? Insurers vary rates widely depending on what neighborhood you live in, for reasons that are far from clear. Insurance firms claim that geography is correlated with loss, but car insurers are famously opaque about the data and algorithms they use to set geographic rates, claiming that this information represents trade secrets.

But just as with housing discrimination, we can observe the effect of these algorithms in practice. And there are some consistent patterns. A growing body of evidence suggests people who live in predominantly Black neighborhoods pay higher prices than otherwise similar drivers who live in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Higher auto insurance rates in Black neighborhoods, even for safe drivers

Most recently, insurance website Insurify analyzed the variables that most influence automobile insurance rates. It found that drivers with good records living in predominantly African-American neighborhoods paid higher rates, on average, than drivers with “incidents” — i.e. a previous crash or serious violation — in predominantly white neighborhoods. As Insurify’s chart below shows, safe drivers in Black neighborhoods pay about $2,100 per year on average, which is more than the roughly $1,700 to $1,800 that drivers with bad records pay, on average, in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Overall, the rate premium you pay for being a bad driver is less than for living in a Black neighborhood. Insurify looks in detail at what it calls “aggressive drivers”–those with infractions like reckless driving, failure to yield or stop, street-racing, tail-gating, and hit-and-run driving. Overall, fewer than 5 percent of all drivers fall into this “aggressive driver” category. On average, according to Insurify, these aggressive drivers pay about $350 more more than safe drivers.

That’s a far smaller premium than insurance companies charge to drivers living in predominantly Black neighborhoods compared to white neighborhoods. Insurify’s data show that a safe driver living in a Black neighborhood pays about $700 more than a safe driver living in a predominantly white neighborhood. Insurance rates impose about twice as large a penalty for living in a Black neighborhood than they do for being an aggressive driver. What makes this particularly egregious and ironic is other independent data that suggests that Black drivers are less likely to speed than other drivers.

Insurify’s findings echo what others have reported. There’s a formidable body of evidence documenting these consistent patterns of discrimination.

In 2017, ProPublica and Consumer Reports conducted a detailed comparison of automobile insurance rates charged in different neighborhoods in California, Illinois, Missouri and Texas. It found that on average, otherwise similar drivers paid 30 percent higher premiums if they lived in predominantly minority zip codes.

A 2007 analysis of insurances rates in Los Angeles by Ong and Stoll found that even after accounting for differences in risk of loss at the neighborhood level, rates varied substantially according to the racial/ethnic and economic status of area residents, with higher rates especially in Black and Latino neighborhoods.

It’s likely that these trends can be amplified by the increasing sophistication with which insurance companies vary rates charged to different persons, based on how they shop. The rates that insurance companies charge to different individuals are essentially opaque to outsiders, meaning that the its difficult or impossible to hold companies accountable for the discriminatory effect of their rate-setting.

The solution: Aggregate to much larger geographies

The best way to address this problem is to prohibit automobile insurance companies from setting rates based on excessively small geographies. In theory, it might make sense to vary rates, by say, zip code, if car owners did all of their driving only in the zip code in which they lived. But people drive over much larger geographies. According to the Brookings Institution, the average trip in large US metro areas is seven miles—a distance that spans many zip codes. While some insurance firms are offering “pay by the mile plans,” most insurance places little if any weight in the distance traveled, and to the extent it pays attention to any geographic factors, it’s only where a car is regularly parked at night, not where its actually driven. Even those who live in low claim zip codes may spend much of their time driving in areas with higher claims.

A good first step would be to aggregate rating territories to much larger areas, counties or even better groups of counties like metropolitan areas. While people spend relatively little time driving in their own zip code, metropolitan areas are defined by the federal government to encompass commuting sheds, and most people do most of their driving in the metro area in which they work. There’s clear precedent for this kind of measure: insurance companies have, for example, been barred from using gender to set rates for auto insurance in California and several other states.

Instead of being based on who your neighbors are, your insurance rates ought to be based on how you drive, and how much you drive. Some insurers have developed pay-by-the-mile insurance rates, and some have plans that monitor driver behavior, but these are optional and offer modest discounts. You still get a better deal if you live in the right zip code than if you are a hyper-cautious, low-mileage driver, and that’s not equitable.