A recently disclosed ODOT memo shows that congestion pricing would do a better job of fixing I-5 congestion than spending $1.45 billion widening the I-5 freeway at the Rose Quarter

Congestion pricing would would be more than a billion dollars cheaper, would make traffic on I-5 move faster, and would produce less pollution than widening the freeway.

Widening the I-5 freeway would produce 3 million more annual peak hour car trips than if simply implements congestion pricing.

Greener and safer: Pricing would dramatically reduce traffic in the Rose Quarter, reducing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, cutting the number of crashes and improving safety, especially for bikes and pedestrians.

ODOT has failed to analyze how congestion pricing would affect Rose Quarter traffic, or to treat it as a reasonable alternative to freeway widening—a clear violation of the National Environmental Policy Act.

ODOT’s congestion pricing model results directly contradict claims made in the Environmental Assessment that freeway widening wouldn’t induce additional traffic and pollution. The sensitivity analysis modeling shows freeway widening would increase traffic and pollution by 7 to 14 percent compared to a “No Build” scenario. The modeling also shows that freeway widening would result in slower southbound speeds than the No Build in the morning peak hour.

For decades, economists and transportation scholars have known that peak hour congestion is a product of our failure to accurately price roads. Under priced roadways lead to congestion and delay–just as Ben and Jerry’s “Free Ice Cream Day” leads to lines around the block. Highway departments have been in desperate denial of this economic fact, but a secret memo from the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) shows that even highway engineers acknowledge pricing would work much better than expensive expansions.

This is a critical question for the proposed $1.45 billion I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project. This project’s Environmental Assessments have steadfastly maintained that pricing of area freeways is “unforeseeable”–even though the agency is counting on toll revenues to pay for the project. As a result, ODOT has almost completely omitted any analysis of tolling from the project’s environmental review. But there is one exception—this July 21, 2022 memorandum from ODOT, looking at how congestion pricing would affect I-5 traffic levels.

A bit of background: The 2017 Oregon Legislature directed the Oregon Department of Transportation to develop a plan for value pricing for I-5 and I-205 between Wilsonville and the Columbia River. Around the world, road pricing has proven to be an effective tool for shifting travel demand and reducing congestion. More than four years ago, ODOT consultants testified that congestion pricing would provide just as much congestion relief in the Rose Quarter as widening the freeway–a finding that this new secret memo confirms. Despite clear legislative direction to implement pricing, and unequivocal analysis from its own experts, ODOT has simply ignored how congestion pricing could be used to reduce traffic in the Rose Quarter. ODOT has dragged its feet in implementing this plan (its already been five years since the Legislation direction pricing was signed into law).

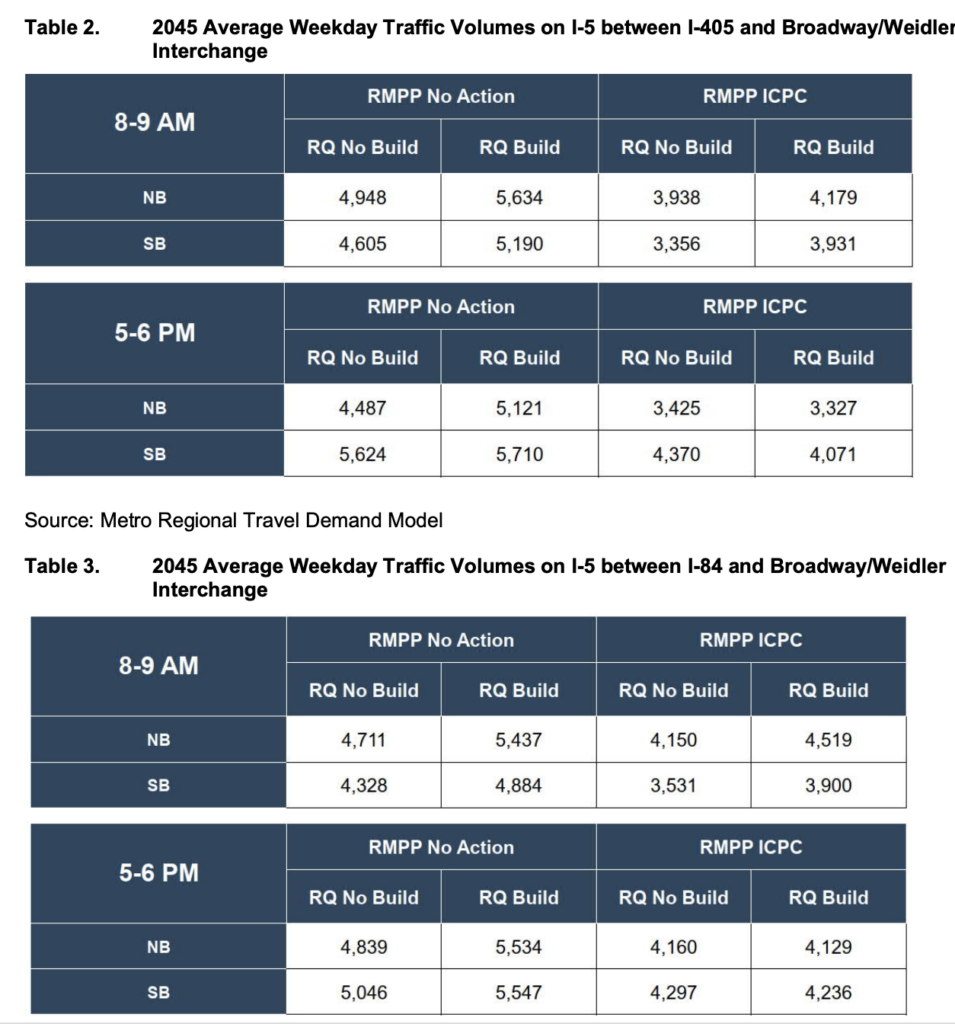

This memo summarizes the results of traffic modeling that look at traffic levels in the Rose Quarter area depending on whether the I-5 freeway is widened (or not) and whether road pricing is implemented. Road pricing has yet another new name in this memo (RMPP-ICPC: “Regional Mobility Pricing Project/Initial Congestion Pricing Concept”. The idea is that ODOT will charge time-based tolls (that vary hourly) to regulate traffic on I-5 and I-205 in the Portland area. This modeling shows how that very basic pricing program will affect traffic levels depending on whether ODOT widens the I-5 freeway or leaves it just as it is.

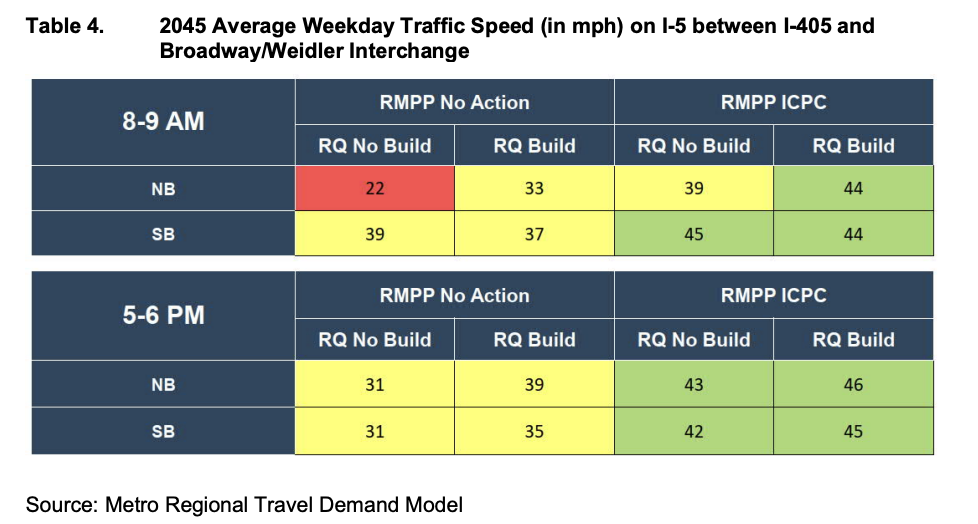

Here’s a key table summarizing the results for the section of I-5 North of the Broadway-Weidler interchange and the Fremont Bridge. This is at the very heart of the area affected by the Rose Quarter project. The two left hand columns (RMPP No Action) correspond to no pricing of I-5 and I-205; the two right hand columns (RMPP ICPC) correspond to variable time based tolls. Each pair of columns corresponds to either not building (not widening) I-5 or “RQ Build” spending up to $1.45 billion to widen a 1.5 mile stretch of the freeway.

Let’s focus in on the PM peak hour. Look at the difference between the “price but don’t build” scenario. Average travel speeds are 42-43 miles per hour with pricing—even if you don’t spend a dime widening the freeway. This is noticeably faster than if you widen the freeway but don’t implement pricing (in which case traffic moves at 35-39 miles per hour). In short: pricing I-5 would result in a bigger improvement in highway speeds on this key segment of I-5 than spending $1.45 billion to widen it. Of course, if you widen the road and price it, you get even higher speeds (45-46 miles per hour—but thats only a 3 mile per hour increase in peak hour speeds for spending $1.45 billion.

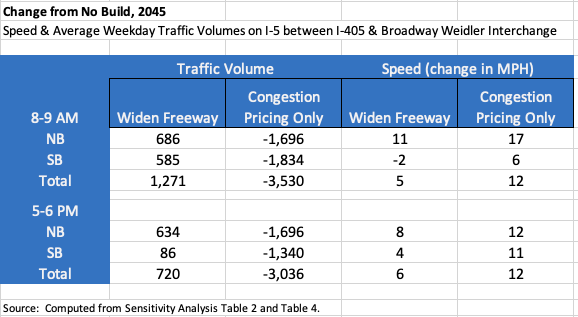

Here’s another way to look at it. Let’s consider two possible alternatives for 2045: Road pricing the existing (No-build) roadway or spending $1.45 billion to widen I-5 but not implement pricing. How does traffic performance change between the “No build with pricing” and the “Widen with no pricing”? It turns out that pricing alone is far more effective in speeding traffic than widening alone. Pricing results in vastly lower peak hour traffic and faster peak hour speeds that widening the freeway and not pricing it. This table shows how traffic volumes and speed change from the “No Build” scenario with two different alternatives: widening the freeway (without pricing), and just implementing congestion pricing.

If congestion pricing were treated as an alternative (which it should be) in the Environmental Assessment, it would dramatically outperform the freeway widening alternative. To see why, let’s compare traffic speeds and traffic volumes in 2045 between the two alternatives. Congestion pricing alone would reduce traffic by 6,500 vehicles in the two peak hours compared to the no-build, while freeway widening increases traffic by 2,000 vehicles in the peak hours. The difference between the two alternatives is dramatic: In 2045, if we implement congestion pricing but don’t widen the freeway that means there would be 8,500 fewer vehicles transiting the Rose Quarter in the peak two hours. Thats over 3.1 million fewer vehicles per year traveling through the Rose Quarter during just two peak hours.

At the same time, congestion pricing results in higher speeds on I-5, than widening the roadway. Congestion pricing would increase speeds on I-5 by about 12 miles per hour on average during peak hours, about twice as much as widening the freeway–widening the freeway, but not pricing it increases average peak hour speeds by only about 6 miles per hour. The data here clearly show what economists have been saying all along: Only by pricing roadways can you reduce congestion and improve travel times. Wider roads are less effective in speeding traffic than road pricing.

But wait, there’s more: Smarter pricing would work even better

This memo reports that ODOT used a fairly “dumb” system of road pricing: rates that would vary hour-by-hour, but wouldn’t fluctuate with traffic levels. The most sophisticated pricing systems use real-time traffic flow information to adjust toll levels down and up to keep traffic flowing smoothly. If ODOT had modeled this kind of real-time variable pricing instead of a fixed hourly schedule, its almost certain than the pricing-only scenarios would have performed even better.

The ODOT modeling also reports travel speeds for the segment of I-5 between I-84 and Broadway-Weidler. Here pricing speeds traffic, but is less dramatic than for the segment between I-5 and the Fremont Bridge. But there’s an obvious reason: the RMPP-ICPC applies only to I-5 and I-205 and not to I-84. There’s a whole lot of I-84 traffic that isn’t tolled, and therefore is unmetered, and ends up clogging the Broadway-Weidler interchange. It’s remarkable that traffic speeds fall so sharply South of Broadway-Weidler—but this is most likely an artifact of what roads are tolled and which aren’t.

Missing Toll Levels

The ODOT Memo is silent about a key feature of the tolling: What level of tolls would be charged under the RMPP-ICPC. They clearly can’t have done the modeling without knowing what the level of tolls would be, but their memo conspicuously avoids revealing this key detail. Technical work done for ODOT in 2018 developed the concept of the RMPP, and proposed tolls of 17 cents to 38 cents per mile for I-5. But ODOT doesn’t want to tell anyone whether that’s the toll level that’s assumed in this modeling.

Violating NEPA

The National Environmental Policy Act requires a careful analysis of reasonable alternatives. ODOT’s own analysis shows that road pricing would be a reasonable and effective solution to traffic congestion at the Rose Quarter. It’s time for them to treat this as an alternative, or even more realistically, incorporate pricing into its estimates of “No-Build” traffic levels.

It is apparent from ODOT’s communication that they aren’t considering pricing as either an alternative or part of the “No-Build.” They continue to maintain that congestion pricing isn’t “reasonably foreseeaable,” even though its been mandated by state law, and ODOT and the federal government are actively working on implementation, and the Chair of the Oregon Transportation Commission has said the state can’t afford the Rose Quarter project without implementing tolling.

The newly disclosed “sensitivity” memorandoum makes it clear that adding road widening to congestion pricing would result in vastly greater driving and carbon emissions: at least 3 million more peak hour miles driven on I-5

In its review of the Draft EA, City of Portland staff asked how the analysis of pricing was to be interpreted: “What is the conclusion of the Sensitivity analysis related to the traffic analysis? What do you do with it?”

ODOT’s Theresa Rolfhs responded:

ODOT has received questions about whether both the RQ project and congestion pricing are both needed to address congestion on I-5. Findings from this sensitivity analysis show that both the RQ project and RMPP are needed to reduce congestion on I-5 to acceptable levels.

K19071 I-5 Rose Quarter Improvement Project, Supplemental EA City of Portland Report Review Log, I5RQ_Traffic_Tech_Report_City_of_Portland_Comment_log_Responses

Actually, ODOT’s sensitivity analysis shows that either pricing or widening the freeway achieve approximately the same improvements in freeway travel speeds, and that both, together, perform somewhat better. But the claim that “both are needed to reduce congestion to acceptable levels” is not valid: while traffic flow may be somewhat faster with both measures implemented, ODOT has never defined a level of congestion it deems “acceptable.” If anything, widening the freeway actually undercuts the benefits of congestion pricing by adding about 3 million peak hour annual vehicle trips to the Rose Quarter. In addition, if congestion pricing is essential to the project being successful (as this statement implies) than pricing needs to be included in the traffic projections for the EIS. It is likely that because traffic flows would be reduced with pricing, that the size and impacts of the project could be reduced from the size needed for the unpriced roadway that ODOT has purportedly studied in the EA.

Bottom line: The reason we have traffic congestion is that peak hour road capacity is underpriced, encouraging more people to drive than the roads can handle. If we implement value pricing, road congestion eases dramatically. Even the highway department’s own technical studies show this is true.

Pricing: Less traffic, fewer deaths

As we’ve pointed out, the Oregon Department of Transportation has falsely and cynically portrayed the I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening as a “safety” project. There’s no evidence that this is a valid claim, and this sensitivity analysis shows that by reducing car traffic in the area, pricing would actually contribute more to safety, especially for vulnerable road users (those walking or cycling near the freeway on- and off-ramps). The traffic volume estimates provided in the Sensitivity Analysis show that road pricing would significantly reduce automobile traffic in and through the Rose Quarter. This is important for understanding the environmental, safety and community impacts of the project.

The sensitivity analysis shows, contrary to statements in the EIS, that building the Rose Quarter project would increase traffic on I-5 compared to the No-Build. Peak hour traffic would be between 7 percent and 14 percent higher under the “RQ Build” option than under the RQ No Build option, assuming the RMPP program isn’t implemented. (This is relevant because this is what ODOT says is the assumption for the project’s Environmental Assessment).

Second, the sensitivity analysis shows that implementation of the regional mobility pricing program would significantly reduce traffic on I-5 if the Rose Quarter not widened. Table 2 shows that traffic between the Broadway-Weidler Interchange and I-405 would be more than 20 percent less if pricing is implemented and the Rose Quarter project isn’t built.

This reduction in travel is important for many reasons: It means that there will be fewer cars traveling through the Rose Quarter, reducing pollution emissions in the local area. Lower levels of car traffic mean lower levels of emissions. Reducing car traffic on I-5 is also likely to reduce to reduce the number of cars entering and exiting the I-5 freeway, and lower car traffic in turn lowers risks to vulnerable road users.

Contradicting claims made in the Environmental Assessment

The Rose Quarter Environmental Assessment, released in 2019, made the preposterous claim that widening the I-5 freeway wouldn’t increase traffic or emissions compared to the No-Build. ODOT never released detailed traffic data or modeling to support this conclusion, and still hasn’t released data on average daily traffic (ADT) the most fundamental measure of traffic volume. And in its traffic technical analysis for the Revised Environmental Assessment, dated June 2022, the agency has indicated that its standing pat on that dated (and still largely secret) traffic modeling.

But the newly released data in the sensitivity analysis memo flatly contradicts the claims made in the original EA modeling. Ignoring the pricing scenarios, the sensitivity memo shows that widening the Rose Quarter freeway will produce more traffic on I-5: In the two peak hours for which traffic data are revealed, the build scenario increases traffic by 13 percent (AM) and 7 percent (PM). This is plainly evidence of the effects of induced demand: expanding freeway capacity leads to more driving. Widening the I-5 freeway results in nearly 1,300 more vehicles in the AM peak hour and 700 more vehicles in the PM peak hour.

This traffic analysis is also not consistent with claims made in the Revised EA that the project will have a trivial net impact on vehicle related emissions in the project area.