ODOT proudly spends road funds on mitigating the impact of its highways: if you’re an invertebrate.

The highway department mitigates noise pollution, rebuilds jails, and even compensates neighborhoods

But if we repeatedly pushed highways through your neighborhood, all you’ll get is condolences, wider overpasses, and a pictures of housing for which there’s no money

The Oregon Department of Transportation regularly spends millions of dollars to mitigate and offset the damage its highway projects due to plants and animals, to wetlands, to the quiet of residential neighborhoods. They’ve made a practice of creating mitigation banks, that offset past and future damage from highway projects. And they’ve even set up permanent funds to provide for the maintenance of these areas over decades.

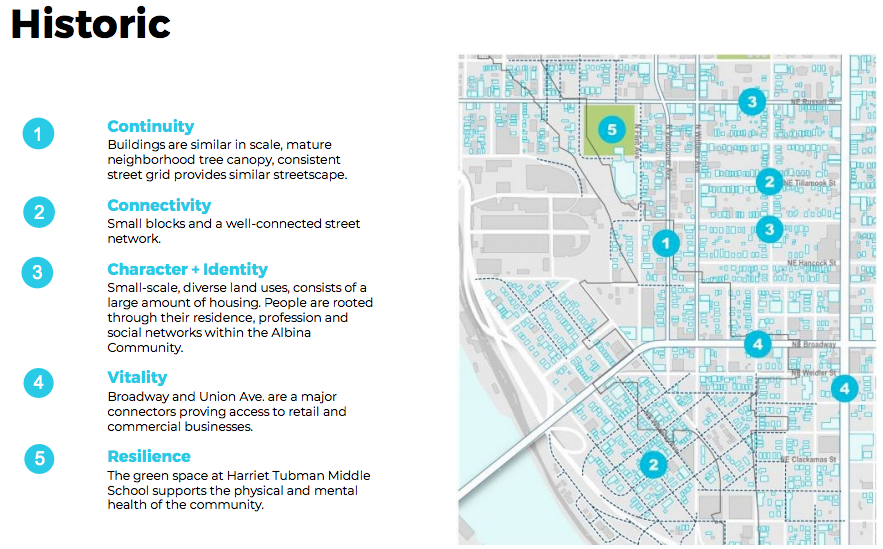

ODOT talks a good game about its interest in offsetting the damage freeway construction did to the historically Black neighborhoods of North-Northeast Portland, but the damage they really did was in wiping out housing, and destroying the critical mass of population in the neighborhood, turning it into a car-dominated landscape of parking lots, drive-throughs and gas stations. At City Observatory, we’ve shown that ODOT highways were principally responsible for decimating the Albina neighborhood. ODOT’s Highway 99W (Interstate Avenue) cut the neighborhood off from the river and demolished houses in 1951; the I-5 Freeway cut the neighborhood off from the rest of North and Northeast Portland in 1962, and the unfinished Prescott Freeway flattened another portion of Albina in the early 1970s. Together these freeway projects and the changes they enabled caused the neighborhood’s population to decline by two-thirds. (The red bounded areas below were largely destroyed by ODOT highway construction).

The most tangible way to achieve “restorative justice” in Albina is to do what the agency routinely does around the state: restore the habitat it destroyed. In an urban setting, that habitat is, most critically, housing. ODOT demolished hundreds of housing units for the i-5 Freeway, and the traffic its roads generated destabilized the neighborhood and wiped out most of the rest. Building housing, lots of it, in Albina, a neighborhood that’s poised for a comeback, would be a fitting way to mitigate the harm it has done.

Instead, the agency seems bent mostly on a superficial effort to sell a wider overpass. If it’s serious about reparations for the damage it did to Albina, ODOT should be making a major contribution to restoring housing in the neighborhood.

ODOT’s routinely pays to mitigate the damage its highways do

It’s hardly far-fetched to suggest that ODOT fix the damage that its projects do to the surrounding environment. ODOT has established mitigation banks to restore disturbed wetlands, fish spawning areas and seasonal ponds. It pays for extensive sound walls to block the noise generated by highways that affect nearby homes and businesses.

Here’s a classic example: In Southern Oregon, highway construction has wiped out hundreds of acres of “vernal ponds”—areas that flood in the rainy season and dry out the rest of the year. These ponds are home to some distinct plants and animals, like the fairy-shrimp and wooly meadowfoam. Recognizing the damage that previous freeway construction had done, and in an effort to offset that (and likely future damage) ODOT has created an 80-acre conservation bank as part of its project to expand Highway 62 in Southern Oregon. In all, ODOT Has more than 200 acres of oak savannah and vernal pools in Southern Oregon. Importantly, ODOT’s own report describes the establishment of the habitat as “compensatory” for the damage done by past, present and future roadbuilding.

Perhaps even more importantly, ODOT’s investment is actually prospective: It recognizes that its future actions will likely cause even more damage to the environment and its created more habitat that its destroyed, in effect to serve as bank to offset likely future damages. ODOT paid to acquire the land, and set up a half-million dollar endowment to assure that exists, in perpetuity.

The Oregon Transportation Commission has already approved nearly $3 million in funding for another mitigation bank called the Columbia Bottomlands. It’s designed to offset damage to wetlands from future projects, including the proposed effort to revive the Columbia River Crossing (Oregon Transportation Commission, December 6, 2019, Consent Agenda, Item 13).

Other major ODOT projects have similar mitigation expenditures. For the Newberg-Dundee bypass, ODOT is creating twice as much wetland habitat as the project is destroying. For the Pioneer Mountain-Eddyville project, ODOT paid for improving fish habitat on nearby streams. ODOT makes all these payments to mitigate environmental damage, in part, because it is required to do so by the National Environmental Policy Act.

Sound walls to mitigate freeway noise

When freeways were first built in the 1950s and 1960s, the state highway department did nothing to offset the effects of noise on nearby homes and businesses. But since the 1970s, it has become commonplace to spend a portion of any project’s budget on “noise walls” to buffer nearby uses. An extensive set of sound walls is proposed as part of the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening project.

ODOT’s guidelines suggest that it will pay up to $25,000 per residence for sound reduction. Nationally there are more than 2,700 miles of sound walls; in just the three-year period 2008-2010, the Federal Highway Administration spent roughly half a billion dollars on sound wall construction. Recently, ODOT spent $2.6 million on a sound wall to benefit several dozen homes in South Salem near I-5. It’s particularly important to note that much sound wall construction was remedial and retrospective: the first noise walls were built years or decades after the freeways were first built, they were an intentional effort to correct past damage.

Highway money for jails and some neighborhoods

In 1980, the right of way for the I-205 East Portland Freeway passed through the site of the Rocky Butte Jail. The Federal Highway Administration paid $53 million (over $160 million in today’s dollars) for the construction of the Multnomah County Justice Center in downtown Portland.

There’s even precedent for compensating for the negative effects of freeways on surrounding human neighborhoods. When ODOT built the I-405 freeway through Northwest Portland in the 1970s, it created a multi-million dollar community development fund. The chief difference: Northwest Portland is a largely white neighborhood; Albina was a largely Black neighborhood. The fund still exists and is now administered by the Oregon Community Foundation, but still gets its funding from highway-related revenues. Among other things, the fund has supported the renovation of the Hillside Community Center in the Northwest hills. For the record, when ODOT built the stub-end of the never-completed Prescott Freeway through Albina in 1973, it didn’t create a similar fund for the predominantly Black neighborhood devastated by construction.

Other governments have sought to mitigate their neighborhood impacts by building housing. The University of California San Francisco’s medical campus has agreed to build nearly 1,300 units of housing, with one-quarter of them reserved as affordable, as part of a community benefits package associated with the approval of the expansion of its Parnassus Heights Hospital. And this is being paid for by the University, not the city. The explicit purpose of the agreement is to offset potential damage to the neighborhood according to San Francisco Supervisor Dean Preston:

“Just as a doctor’s oath requires them to do no harm to their patients, we want to make sure that the UCSF development plans do no harm—and in fact, benefit—surrounding communities and the city,”

The need for reparations in Albina

Just as fish ladders on dams only partially mitigated the epic destruction of native salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest, building covers over a widened freeway is only the most minimal mitigation of the damage done to Portland’s historically Black Albina neighborhood.

ODOT’s map of the project area makes it clear that in 1954, prior to the construction of the freeway there were hundreds of houses, and that the gridded, walkable fabric of Albina was very much intact. It wasn’t simply the construction of the freeway that transformed the area, it was the flood tide of car traffic that rendered much of the area inhospitable to residential inhabitation. As we’ve documented at City Observatory, these ODOT highway projects led to the loss of hundreds and hundreds of housing units and led to a decline in population in Albina from more than 14,000 in 1950 to about 4,000 in 1980.

Whether we’re talking mitigation or reparations, ODOT owes this neighborhood something much better that a few hundred square feet of noisy, largely unusable or undesirable space on a freeway cap, surrounded by an increasing flood of automobile traffic. Instead, it should be looking to mitigate the damage to the neighborhood in exactly the same fashion it did for Highway 62 in Southern Oregon: by restoring the pre-existing habitat. The way to do that is not through freeway covers, or a single building site atop a freeway overpass, but by subsidizing the construction of hundreds of housing units that can restore the density, urban form and walkability of Albina that existed prior to the freeway’s construction.

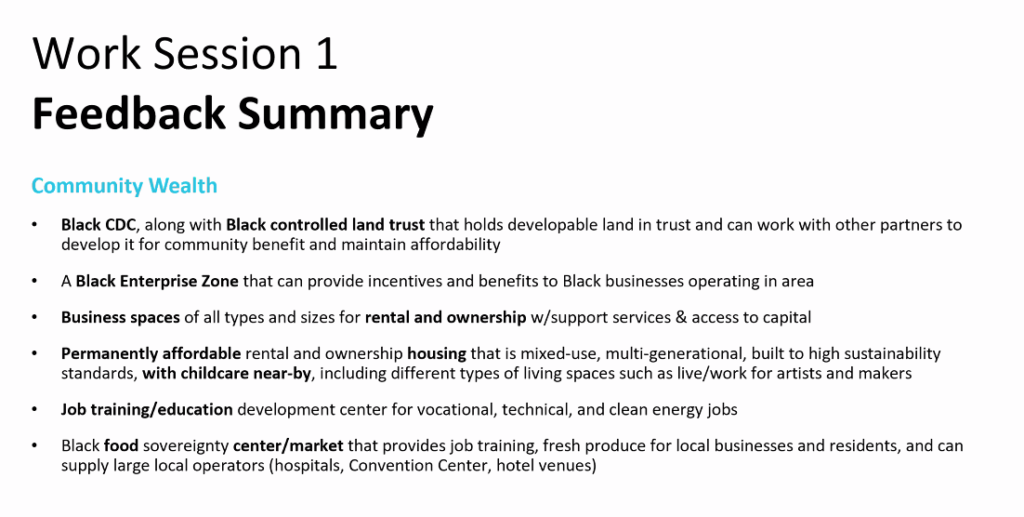

The Rose Quarter project’s own public outreach process highlighted the construction of permanently affordable housing as a key strategy for restoring community wealth in Albina. (Executive Steering Committee presentation, March 22, 2021).

And while ODOT’s “Independent Cover Assessment” consultants have produced illustrations showing how as many as 750 new apartments could be built on or near the Rose Quarter project, ODOT hasn’t come up with a single dime of the $160 to $260 million it would cost to build the housing depicted in its images.

To sum up: ODOT can spend real dollars when it comes to protecting vernal ponds, restoring wetlands, improving fish habitat, or lessening sound impacts on nearby houses. It can use highway dollars to replace jail cells. It can even contribute money for neighborhood improvement—at least in historically white neighborhoods. But when it comes to North/Northeast Portland, where their freeway intentionally targeted and wiped out hundreds of housing units (which they never replaced), and whose traffic destabilized the neighborhood, and led to decades of decline, ODOT has, at most, condescending rhetoric, and feeble and misleading promises about “freeway covers” which in fact are badly fragmented, noisy and pedestrian hostile land perched over a widened I-5 freeway..

Why doesn’t ODOT recognize the habitat of Albina as worthy of protection and recompense? If it can restore twice as much wetland as a freeway destroyed, why can’t they restore twice as much housing as they demolished?