What City Observatory did this week

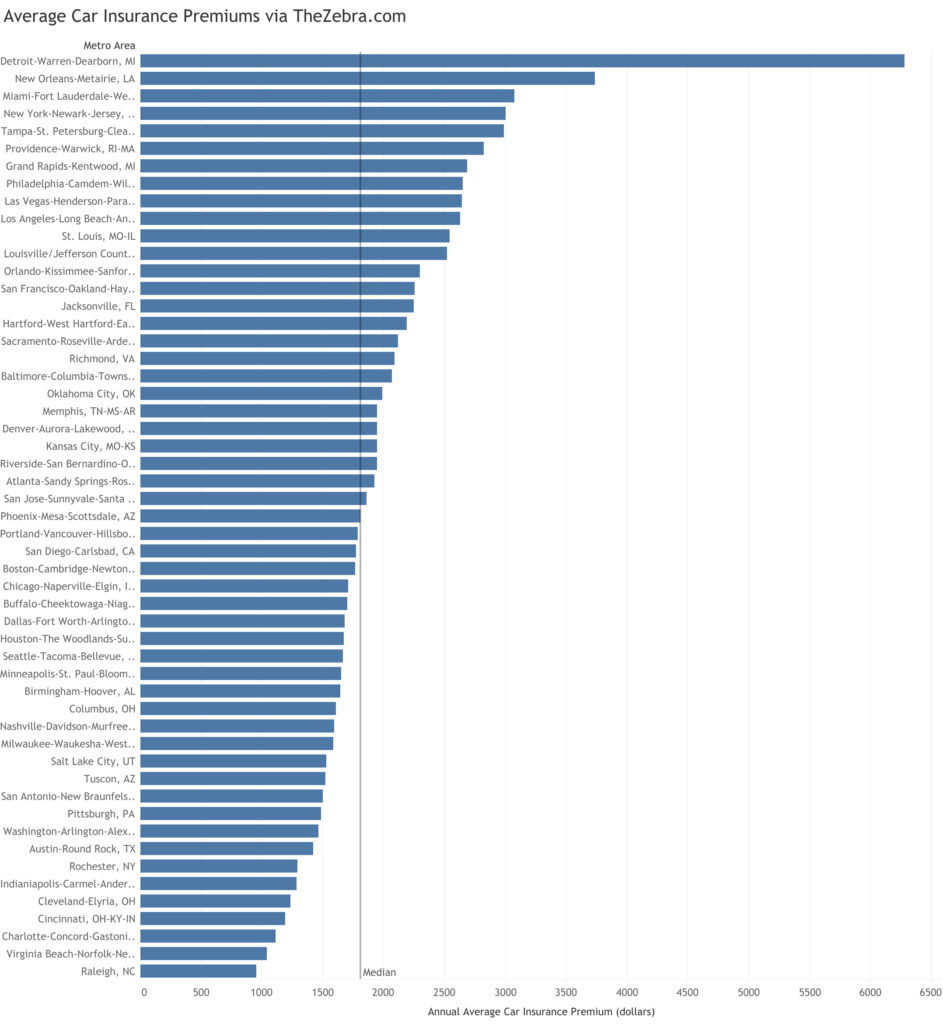

Cost of Living and Auto Insurance. We often compare the affordability of different cities with a clear focus on housing prices and rents. This week at City Observatory we are interested in the role that insurance plays in the cost of living across metropolitan areas. Location has a major influence in the amount of money consumers pay to insure their assets. A driver in Detroit can pay thousands of dollars more insuring their car than a driver in Chicago. Why? Here, we explore the notable variation of auto insurance across the largest metropolitan areas in the United States and consider the reasons for these differences.

We find that Detroit, New Orleans, and Miami have the highest annual auto insurance rates and that there is wide variation across metro areas. Racial demographics and state insurance policy appear to be major players in this variation. Millions of Americans drive their cars every single day. A car dependent society is reliant on car insurance as well. Rates can make a major dent in your wallet every year and where you live may be the reason why.

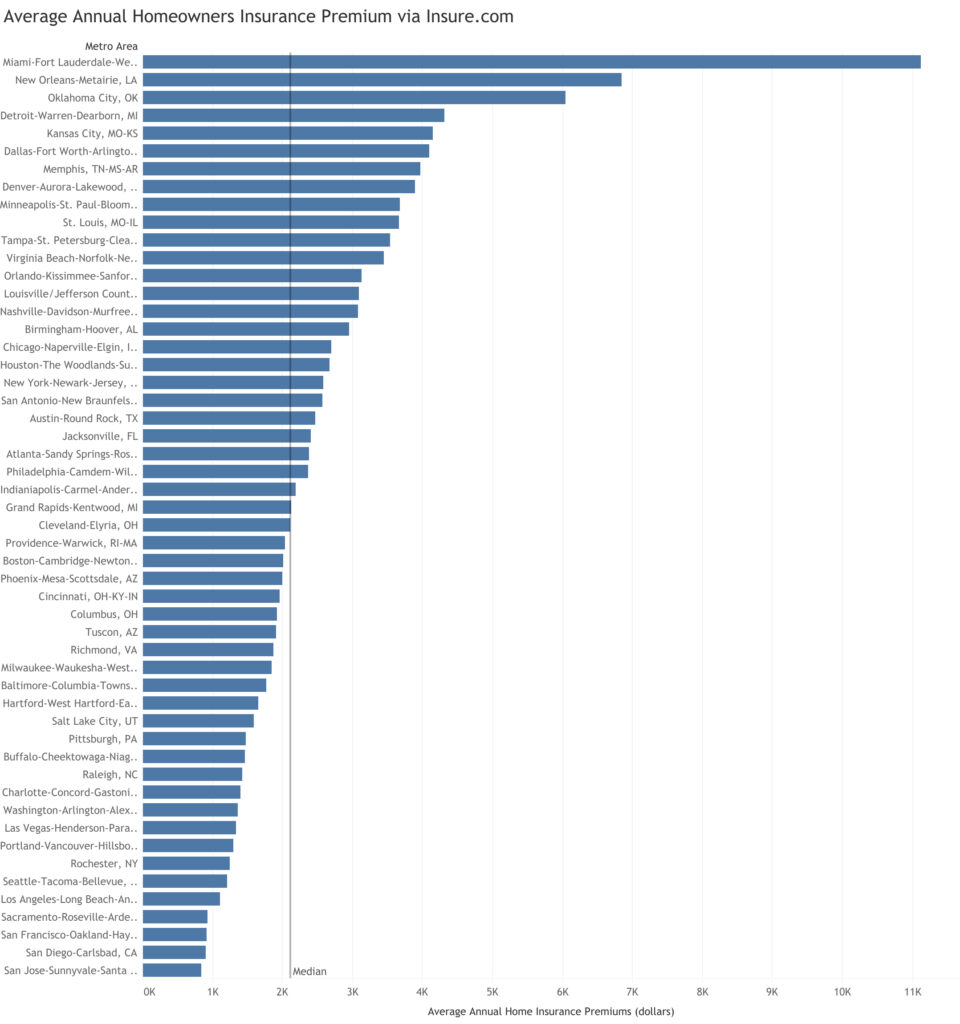

Cost of Living and Homeowner’s Insurance. The impacts of climate change on our built environment have been increasing in recent years. Disaster payouts from reinsurers, the firms that insure the insurance companies, were the fifth highest in history last year. As the world becomes a more volatile place, homeowners insurance rates will be adjusted accordingly. In this piece, we examine how homeowners insurance rates vary across the largest metropolitan areas in the United States and how these rates contribute to the overall cost of living. What we found – Miami, New Orleans, and Oklahoma City had the highest rates while five California metro areas had the lowest.

The risk of extreme weather in Southern cities appears to heighten the rates of homeowners insurance. As a result of this, insurance rates in generally affordable metro areas like Oklahoma City and Memphis heighten the overall cost of living, potentially high enough to cancel out the lower rents. Homeowners insurance rates have notable variation across the metro areas. In the future, the price of insuring your home could have a significant influence on the overall cost of living in disaster-prone metropolitan areas as we continue to experience the impacts of climate change. When the risk for extreme weather increases, the role of insurance will increase too.

Must read

1. Vancouver considers road pricing. No urban center in the United States has implemented an extensive pricing system that charges vehicles for road usage. Vancouver, BC may be the first. Back in 2018, the regional transportation authority, TransLink, commissioned a mobility pricing study. What they found in Metro Vancouver were “increased travel time reliability, reduced traffic and a potential reduction in transit fees, among others.” Last November, the city began a $1.5 million study into mobility pricing. While a politically challenging solution, mobility pricing appears to be a great policy tool for reducing greenhouse gases and encouraging other transportation options. Vancouver is a city with goals to reduce congestion and improve its carbon footprint, hoping to be the greenest city in Canada. If they really desire that title, charging vehicles for road usage may be a impactful solution.

2. Colorado greenhouse gas budget for the highway system? Colorado Public Radio reports that Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) has published a rule that would tie future transportation system investments to progress in meeting the state’s adopted greenhouse gas reduction goals. At first glance, this seems like an important step in the right direction: If Colorado regions aren’t making progres toward greenhouse gas reduction goals, they should shift their spending measure that encourage transit, walking and cycling, and de-emphasize road capacity. There’s a strong parallel here to the Clean Air Act, which limits highway construction in places that have failed to achieve attainment for national air quality standards. In broad brush terms, the regulations do that, but with an important asterisk: they assume that the state will make heroic progress in the adoption of electric vehicles. What happens, it will be interesting to know, if EV adoption falls short of the state’s very optimistic assumptions? As always with policy measures, and climate policies in particular, the devil is in the details.

3.Interview with Courtney Cobbs: Issues of equity and sustainability are deeply intertwined in transportation systems across the United States. Courtney Cobb, co-editor of Streetsblog Chicago, writes about the intersection of these issues, seeking to improve Chicago’s transportation. Here, she answer questions about sustainable transportation in the Windy City. Cobb explains the lack of focus on the city’s transit system and the need for better bus and bike infrastructure. When asked what she could redesign Chicago’s transportation, she states, “The vast majority of our buses would have priority on the streets. So they would have their own dedicated lane, they would have signal priority where the lights change to benefit the bus.” The advocate expresses her vision for the future and how to incorporate equitable solutions into Chicago’s transportation system. Cobb gives an eloquent interview about the current state of Chicago’s transportation, the improvements it needs, and what it could transform into