What City Observatory Did This Week

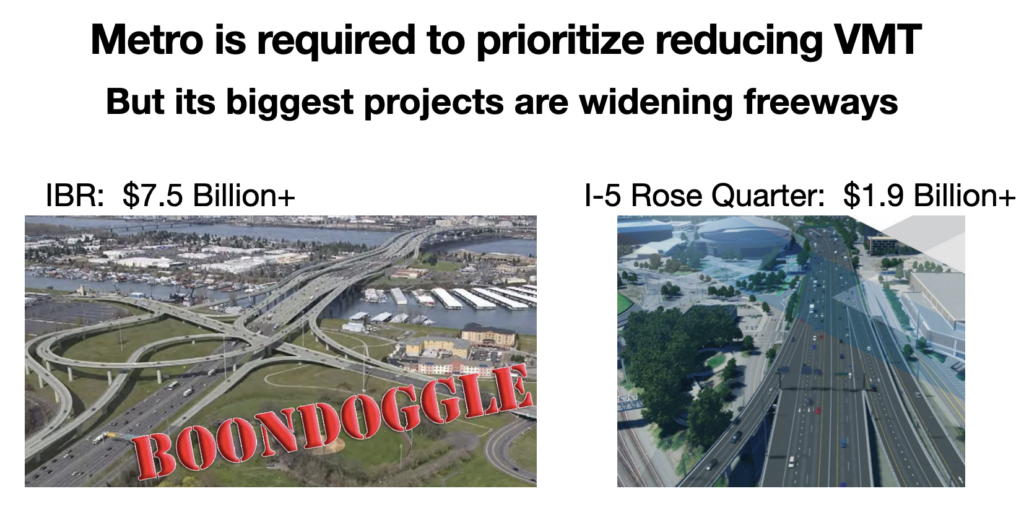

How Metro’s RTP illegally favors driving and violates state climate rules. Oregon’s planning rules require Portland area transportation plans to prioritize investments that reduce vehicle miles traveled–but the region’s transportation plan illegally prioritizes spending for freeway expansions.

Metro’s adopted Regional Transportation Plan devotes most of its resources to providing additional capacity for car travel. Metro’s own climate analysis shows investments in roads are the least effective way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Transit, biking, walking and compact development are all more effective and less costly–but get only a small fraction of regional investment.

Instead of prioritizing these greener investments, Metro’s plan actually increased the amount of money being spent on the dirtiest forms of transportation. The share of RTP funding going to support cars and driving increased from 56 percent in the 2014 Climate Smart Strategy to 68 percent in the 2023 RTP. By devoting more funds to cars and driving, Metro’s RTP is short-changing transit, biking and walking, all of which lower carbon emissions.

Metro’s RTP is subject to review by the state Land Conservation and Development Commission, which should reject the RTP.

Must Read

Measuring the Civic Commons. Our friends at Reinventing the Civic Commons (RCC) have been leading a national effort to show how revitalized public spaces, including parks, libraries and neighborhood streetscapes can play a key role in building social capital. As we and others have noted, we have less in common—the social fabric of the United States has frayed over the past several decades as we’ve become more distant from one another in our daily lives.

To their credit, the RCC partners have put great emphasis on measurement to evaluate the effectiveness and impacts of their intervention. They’ve got an interesting set of metrics, and some hopeful initial findings. This article describes their work in a number of areas, including Detroit’s Fitzgerald neighborhood. They’ve found that where they’ve invested in civic spaces, attitudes are changing:

At a time when just 37% of people believe most people can be trusted and the public’s trust in the federal government is dipping toward an all-time low, it is notable when, on a local scale, trust in both people and government increases substantially.

That’s what’s happening in Fitzgerald. Between 2017 and 2023, the percentage of residents who say most people can be trusted nearly tripled from just 13% to 34%. A similar increase was seen in trust of local government, with the percentage of residents who say they can trust their city government to do what is right most of the time growing from 12% to 30%.

How we build our communities to promote social interaction is a vital foundation in building thriving, opportunity rich communities. The RCC measurement tools illustrate how we can move forward.

More and cheaper urban housing should be the Kamala Harris climate policy. Writing at Heatmap, Robinson Meyer makes a compelling argument that Democratic Presidential candidate Kamala Harris should make an expanded housing supply, particularly in greener urban locations, a centerpiece of her climate strategy. A focus on housing directly addresses concerns about living costs and housing availability, and is central to an effective strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As Meyer explains:

In America, where you live determines how much carbon dioxide you emit. . . . half a century of sprawling suburban development has made a high-emissions-lifestyle all but compulsory. If you live in New York, Washington, D.C., or another walkable city, then your carbon emissions are substantially lower than if you live in the suburbs or exurbs. In the country’s sprawling suburbs — not only in the Sunbelt, but also in New Jersey, Maryland, and California — carbon emissions are much higher. That’s because where you live basically determines how much you drive — and driving is America’s biggest climate problem.

Building more housing in denser, opportunity-rich urban areas that are walkable, bikeable and well served by transit can be a foundation of a great national policy that addresses both housing and the environment.

New Knowledge

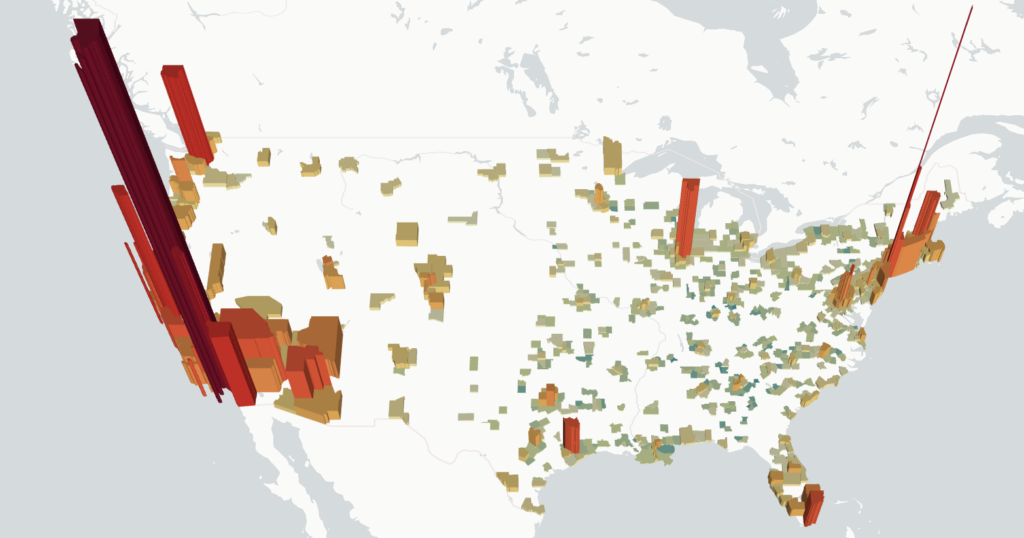

Roads consume vast amounts of land and tie up trillions of dollars that could be better used for other purposes. Wharton economists Erick Guerra, Gilles Duranton and Xinyu Ma have created a comprehensive estimate of the land area of the United States devoted to roads–a measurement that has never existed. They show that the paved area in the US covers land larger than the state of West Virginia, and represents the consumption of $4.1 trillion in value.

In terms of value, the cost land devoted to roads is overwhelmingly concentrated in the largest (and most valuable) urban areas. This map shows the aggregate value of land in roads in the nation’s metro areas. The land in roads in Manhattan is worth $225 billion, in Los Angeles County $313 billion and in Seattle’s King County $76 billion.

These estimates prove what we have long known, at least intuitively–much of our landscape, particularly our urban landscape is given over to cars. The magnitudes are overwhelming, but the real story from this study is that from an economic perspective we’ve devoted far too much land to roads, and that we would be richer–better off economically–if less of our urban land were tied up in roads, and more were shifted to other valuable uses: housing, parks, public spaces, and valuable commercial and industrial buildings.

Guerra, Duranton and Ma estimate the economic effects from a 10 percent increase or decrease in the amount of land devoted to roads. Their work highlights the fact that road expansion has a strongly negative benefit/cost ratio: widening roads destroys more value than it creates through time savings. They conclude:

. . . we found that the estimated costs of increased road investments substantially outweighed the estimated benefits on average, especially when accounting for land values.. Ignoring externalities and land values entirely, the costs of expanding urban roadways exceeded the benefits by a somewhat modest 17%. The external costs of new traffic and especially the opportunity costs of lost urban land, however, were the largest costs of adding road supply. Including the land value, costs outweighed benefits by a factor of nearly three. Including externalities resulted in costs that were four to five times higher than benefits. (emphasis added)

The benefit-cost studies done by highway agencies over-estimate time savings, ignore induced travel effects, discount externalities, and completely omit the land value effects documented in this study. From an economic perspective, in the 21st Century, we’ve gone well past the point of diminishing returns to road investment, and are now in a realm of negative returns. Widening highways destroys economic value.

Guerra, E., Duranton, G., & Ma, X. (2024). Urban Roadway in America: The Amount, Extent, and Value. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2024.2368260