What City Observatory did this week

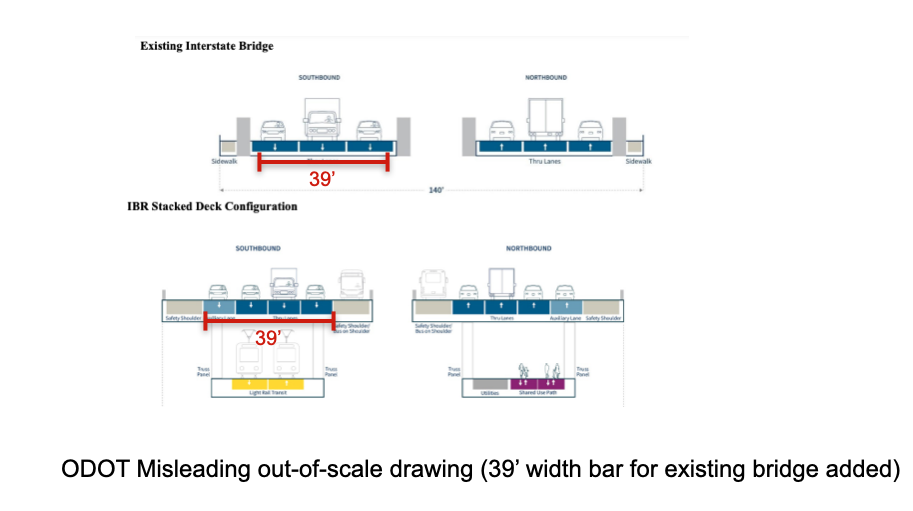

Why can’t Oregon DOT tell the truth? Oregon legislators asked the state transportation department a simple question: How wide is the proposed $7.5 billion Interstate Bridge Replacement they want to build? Seems like a simple question for an engineer. But in testimony submitted to the Legislature, Oregon DOT officials went to great lengths to conceal and misrepresent the true size of the massive freeway bridge they’re planning. The simple fact is ODOT plans to replace a 77′ wide bridge with one that’s more than twice as wide (164 feet) wider than a football field, and enough for twelve traffic lanes.

Lying with pictures is nothing new for the IBR project. As we’ve noted before, despite spending tens of millions of dollars on planning, and more than $1.5 million to build an extremely detailed “digital twin” of the proposed bridge, IBR has never released any renderings showing what the bridge and its mile long approaches will look like to human beings standing on the ground in Vancouver or on Hayden Island. And the IBR also released similar misleading and not-to-scale drawings that intentionally made the height and navigation clearance of their proposed bridge look smaller than it actually is. And for the earlier version of this same project, the Columbia River Crossing, OregonDOT claimed to reduce with width of the freeway from 12 lanes to 10, but instead simply erased all the width measurements from the project’s Final Enviornmental Impact Statement, while keeping the project plans exactly the same.

Must Read

How freeways kill cities. Economists have long recognized that highway construction leads to sprawling and decentralized development by making it easier and cheaper to travel further. But that’s not all, as Street MN’s Zak Yudhishthu summarizes the latest economic findings about highways and cities, highways and cars also damaged the urban fabric, making city living less desirable. They quote Federal Reserve economistsJeffrey Brinkman andJeffrey Lin, as showing showing that freeways also reshaped our cities by creating disamenities for center-city residents.

In other words, freeways do more than just link us together. While previous research assumed that freeways drove suburbanization solely by making suburban life better, Brinkman and Lin find that freeways drove suburban flight by making urban life worse. Freeways can serve as connectors, but they also make it more difficult for center-city residents to access amenities and jobs in their cities, alongside other pollutive reductions in quality of life.

Too often, discussions about the impact of freeways just looks at the direct (and devastating) effects of initial freeway construction. But this is just the first level of harm: the flood of traffic carried by freeways, coupled with noise and air pollution, is caustic to livable neighborhoods, and leads to population loss and business closures, as places near freeways become hostile, car-dominated spaces.

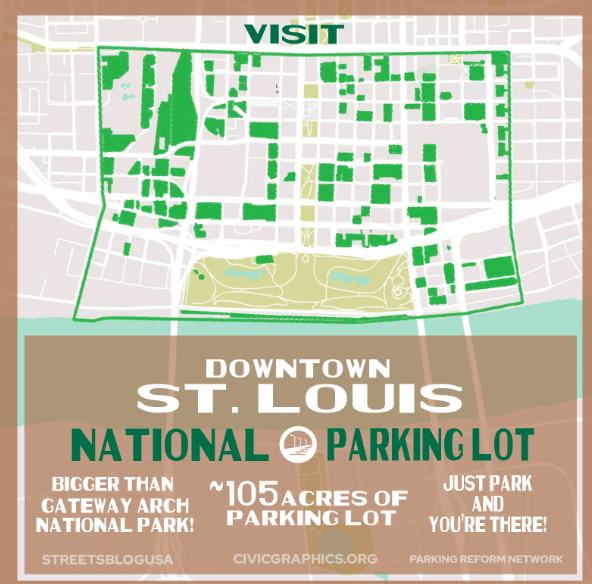

Visit your Nearest National Parking Lot! Streetsblog’s Kea Wilson has a cutting parody of our old school national park posters that highlights how much of our nation’s urban centers has been given over to parking. Building on an illuminating set of maps of parking lots and structures created by the Parking Reform Network, Civicgraphics has created a series of posters highlighting the glories of abundant parking that dominates so much of the urban core.

As Wilson points out, public subsidies to parking (as much as $300 billion annually) dwarf the $3 billion we spend on national parks; so in reality parking lots are more central to our national identity that Yellowstone or Yosemite. It’s a pointed and painful parody to be sure, and it speaks vastly more truth than the fictionalized pedestrian and greenery heavy renderings that are being peddled by highway departments to greenwash road widening projects.

Lessons from California’s first-time home-buyer credit. Housing affordability is famously a California malady. In an effort to blunt the problems that first-time homebuyers face, the California Legislature enacted a “Dream for All” a $288 million loan program to provide down-payment assistance to new homebuyers. While the impulse is understandable, the policy is questionable. The first issue has to do with scale: “for all” is rather grand, and while a quarter of a billion dollars is a lot of money, the program provided loans to fewer than 2,600 California households. In a state with 40 million residents, those are lottery-winner odds. Little wonder, the whole program was exhausted days after starting. The second issue has to do with who got the loans. Sharp-eyed reporters at CalMatters noted that a disproportionate share of the loans went to applicants in the Sacramento area. Apparently, people who worked in and around state government were much more aware and prepared to apply for the program, according to local loan officers:

. . . news of the program spread by word-of-mouth throughout the capital community in the days before the state officially launched the program on March 27. The regional rumor mill may have been churning especially quickly given how much more plugged-in locals are to matters of state bureaucracy. “Sacramento and the surrounding area’s loan officers and Realtors probably got a jump start,” he said.

A final problem has to do with the economics of supply and demand: while the down payment loans ease the burden of ownership for the relative handful of lucky households that get one, they likely increase the number of prospective bidders for the limited supply of homes for sale. While 2,500 more qualified buyers in California might not make much difference, expanding the program would likely create even more upward pressure on home prices, aggravating the affordability problem the program aims to solve.

Building more housing helps hold down rents. There’s a growing body of academic literature showing how building more housing, including new market rate housing–helps hold down rents and address affordability challenges. The problem is that academic literature seldom filters down.to the public. Seattle public radio KUOW has a terrific and non-technical explanation of this literature, featuring an interview with UCLA professor Michael Lens, one of the authors. They frame the question in common-sense terms: Does building townhomes help hold down rents? Part of the answer is that townhomes require less land and less public infrastructure (like street frontage) than single family homes, which lowers construction and development costs. But the more important issue is that by providing more homes, and thereby increasing supply, townhouses help moderate rents. The KUOW report concludes:

. . . here’s what the science and research is telling us so far: Housing density does bring down the cost to build housing. And most studies seem to suggest that yes, this pattern is repeating over and over in cities that reform their zoning to allow more housing.

New Knowledge

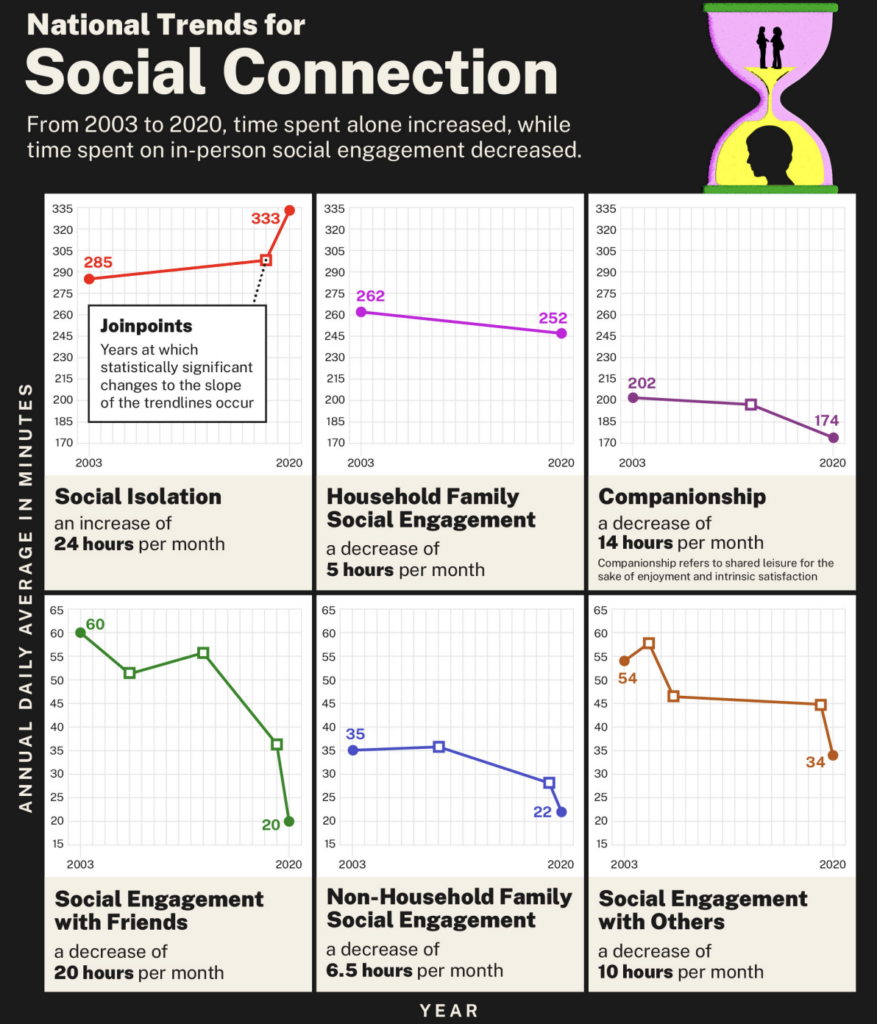

America the lonely and isolated. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has released a new report decrying a growing epidemic of loneliness in the US. In simplest terms, we spend more time apart from one another now than ever before. Across a broad array of indicators, we’re spending less time with others in social settings:

The Surgeon General’s report echoes many of the themes highlighted in City Observatory’s 2015 report “Less in Common“–emphasizing the growing isolation and declining social interaction in daily American life.

What’s striking about this report is that it clearly links isolation and growing loneliness to a range of negative health outcomes. As Surgeon General Murthy writes:

Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling—it harms both individual and societal health. It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death. The mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, and even greater than that associated with obesity and physical inactivity.

To any urbanist, the principle causes of growing isolation will be evident in our landscape. The sprawling, low density development patterns that define our metropolitan areas put us physically further from one another (living largely in single family houses), and require that we spend an inordinate amount of time alone in automobiles as we travel. The failure to connect these social trends to our built environment is a major shortcoming of the Surgeon General’s report. Even though its principal recommendation is to “cultivate a culture of connection,” it doesn’t talk about how the physical environment impedes (or promotes) connections. You won’t find any mention of sprawl, density, commuting or car-dependence in the report.

Half a century ago, the Surgeon General’s report on the health consequences of tobacco helped trigger a major social and policy shift in the way Americans related to smoking. We’ve banned smoking on planes and in most indoor public places, and these bans, coupled with economic incentives and changes in social attitudes about smoking have reduced deaths and respiratory disease. We can only hope that this Surgeon General’s report will lead to similarly helpful changes in our communities, promoting greater social interaction–and expand the scope of that concern to the built environment..