What City Observatory did this week

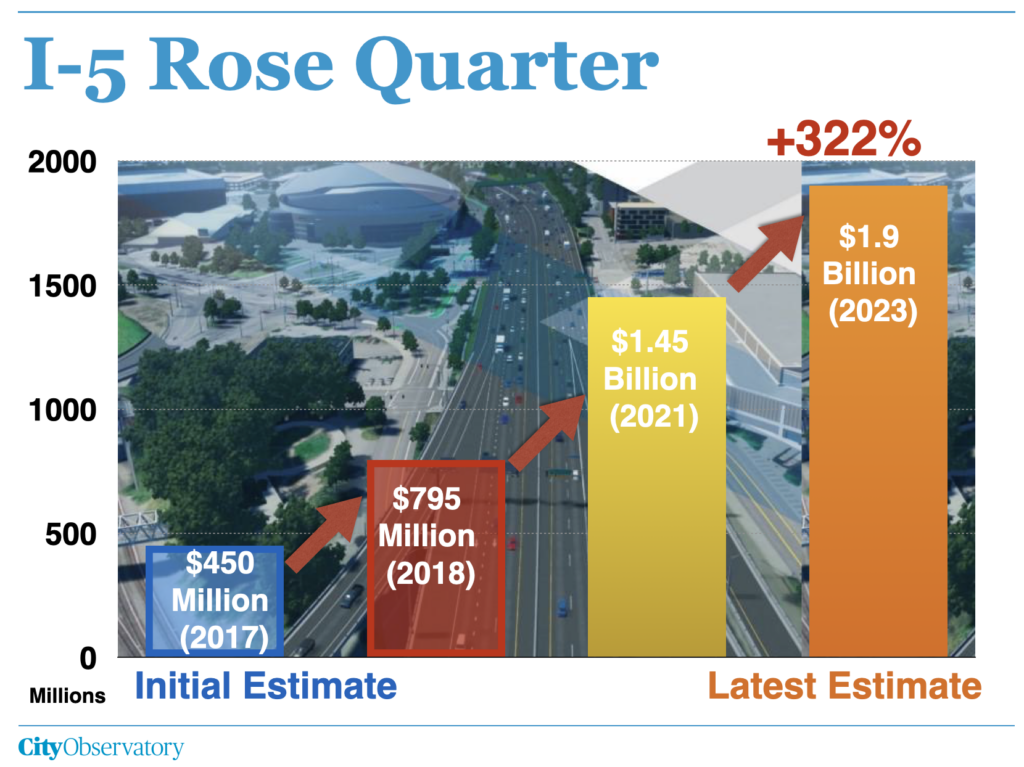

Yet another exploding whale: One of the Internet’s most popular videos shows employees of the Oregon Department of Transportation blowing up a dead whale carcass stranded on an Ocean beach, with bystanders running in terror from a rain of blubber. ODOT’s latest fiasco is the exploding price tag of its 1.5 mile I-5 Rose Quiarter Freeway project. This week the agency announced the price of the freeway widening project in Northeast Portland had increased yet again, to as much as $1.9 billion, more than four times the price quoted to the Oregon Legislature when it voted to approve $450 million in funding six years ago.

In addition to a ballooning price tag, ODOT spent the money the Legislature originally appropriated for the project on another freeway (in Portland’s suburbs) and is, according to OTC Member Sharon Smith “out of money.” It looks like the Rose Quarter is a dead freeway walking.

Must Read

Portland’s “Missing Middle” reforms start bearing fruit. Just a year ago, the Portland City Council approved the city’s “Residential Infill Policy” to allow a greater variety of housing, including multi-plex units to be built in the city’s previously exclusively single family zones. It’s still early days for the policy, but an interim report from the Portland Planning Bureau shows that more housing in the pipeline, on its way to getting built.

The city reports that in its first year, new policy produced permits for 271 units of middle housing (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes and sixplexes) in what were formerly single-family zones. Three-quarters of these were in fourplexes. And over the past year, permits for “middle housing” in these residential zones well outpaced permits for conventional single family homes (just 78 were permitted). This appears to represent strong demand for additional density.

Overall, the policy resulted in approving the construction of about 3.4 units on each lot. Middle housing provides considerably more housing per lot than the city’s permitting of accessory dwelling units (ADUs): the 126 houses and accessory dwelling units built in conjunction with a house were built on 102 lots (about 1.2 units per lot).

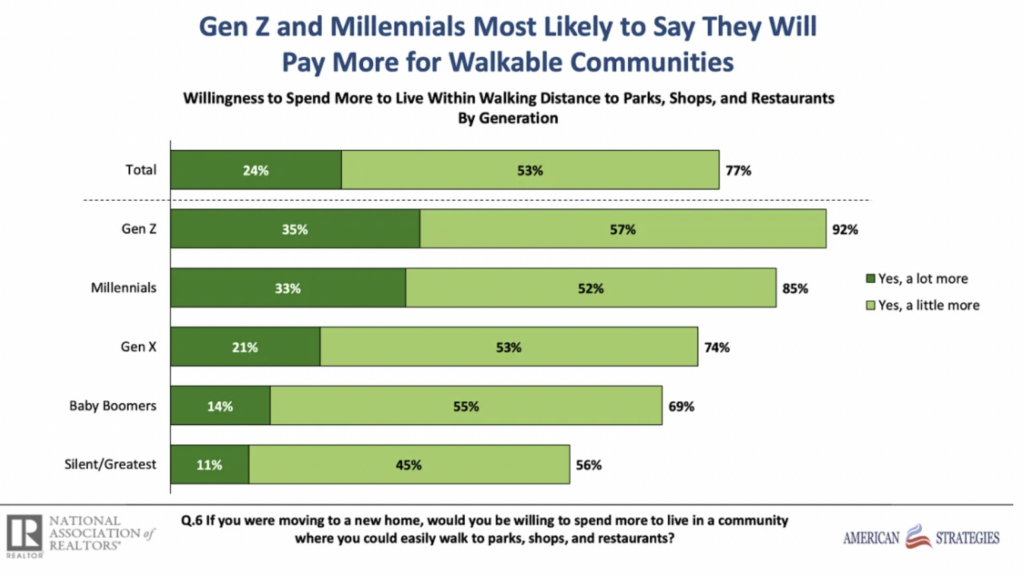

Americans prefer walkable neighborhoods and will pay a premium for them. A new survey from the National Association of Realtors shows that Americans are looking for places that are walkable and have an abundance of amenities and destinations close-by. And importantly, most signal that they are willing to pay more for to live in these walkable places.

The realtor group’s findings confirm a growing body of research, including our own City Observatory analysis, showing that houses with higher walk scores command higher prices than other, less walkable houses, even after controlling for a wide array of characteristics that influence home values. The premium for walkability is an indication that we haven’t built enough walkable neighborhoods in the US, and that we haven’t built enough housing in those places with high levels of walkability.

New Knowledge

Accessibility: Proximity to Activity Centers. Adie Tomer and Caroline George of the Brookings Institution’s Metro program have a new research report looking at the connection between activity centers and travel in the nation’s large metropolitan areas.

The report studies how distance to activity centers (concentrations of workplaces, stores, institutions and other common destinations) influences the travel behavior of households. The study relies on detailed mapping of large US metro areas, and anonymized data from mobile devices to measure travel patterns. Here’s a map showing person miles of travel for the Portland metropolitan area.

The key takeaway is that living in a more accessible location, in this case, defined as being within 3 miles of at least five defined activity centers, produces a significant reduction in daily travel. In Portland, for example, households living within 3 miles of five or more activity centers travel about a third less than households living seven miles or more from 5 activity centers. As Brookings points out, less driving translates into lower travel expense for households–and reduced carbon emissions.

The Brookings report is a helpful reminder that land use patterns–particularly accessibility to a rich set of destinations–is a key to reducing automobile dependence. Essentially what we have to do is reverse the pattern of the past several decades, where people and activities became more dispersed, leading to greater driving, travel cost and pollution.

Metropolitan America has now spent nearly a century undercutting the importance of proximity. Urban land area grew 1.4 times faster than the population between 1960 and 2020, leading to drops in overall population density, significant increases in roadway lane miles, and longer distances between where people live and where they need to go. The result is a multi-decade expansion of the average mileage each person travels per day, or what’s known as PMT: from 19.5 miles in 1969 to 40 miles in 2017. Covering those kinds of distances overwhelmingly favors car usage, so it is little surprise that 92% of American households now have access—often by necessity—to a private vehicle.

Adie Tomer & Caroline George, Building for proximity: The role of activity centers in reducing total miles traveled, Brookings Institution, , June 29, 2023,

Building for proximity: The role of activity centers in reducing total miles traveled

Note: City Observatory reviewed and commented on a prepublication draft of this report; City Observatory was not compensated for its review.

In the news

Axios Portland quoted City Observatory Director Joe Cortright in its story on Oregon lawmakers voting funding for the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project.