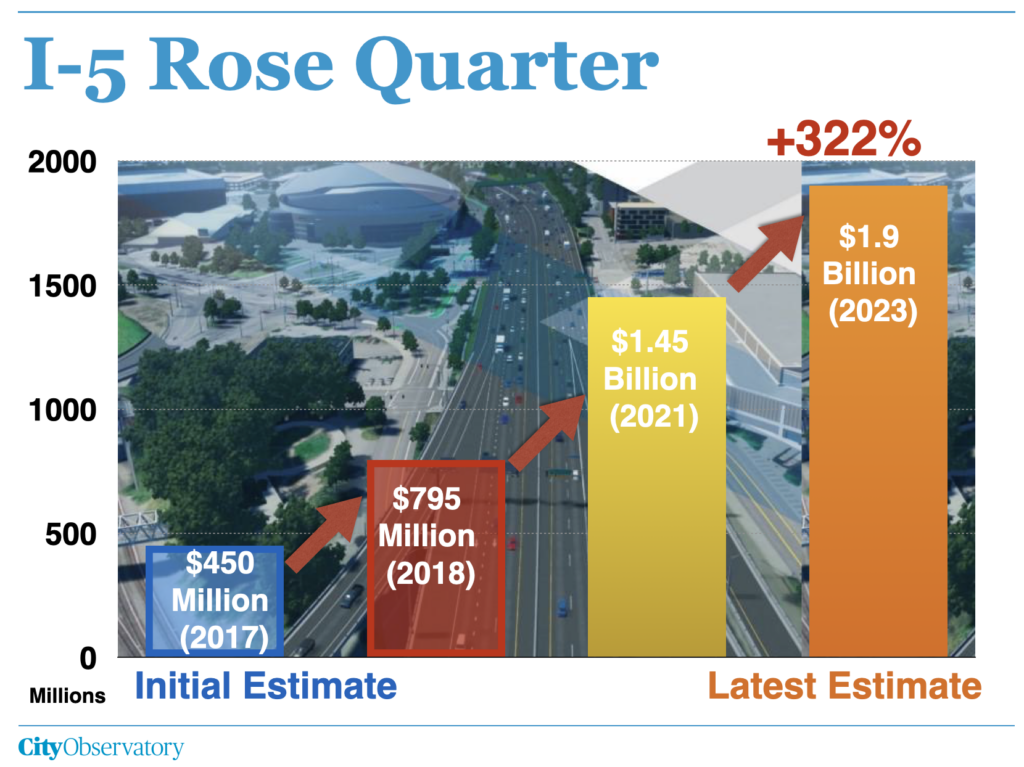

It now looks like Oregon DOT’s I-5 Rose Quarter $450 million freeway widening project will cost more than $1.9 billion

The project’s estimated cost has nearly quadrupled in just six years, and still has further cost overrun risk

Even OTC commissioners question whether it’s worth more than a billion dollars to widen a 1.5 mile stretch of freeway

The Oregon DOT has experienced massive cost-overruns on all of its largest construction projects, and has systematically concealed and understated the frequency and scale of cost overruns

Our metaphor for ODOT project cost management is the famous exploding whale.

One of the most viewed clips on YouTube depicts the handiwork of Oregon Department of Transportation engineers. In the fall of 1970, faced with the rotting corpse of a 45-foot long sperm whale on a Pacific beach, ODOT engineers planted half a ton of dynamite under the carcass; when detonated it created a rain of blubber that sent bystanders running for their lives—a a huge chunk that crushed a nearby car. ODOT has subsequently given up on dynamiting stranded whale carcasses (it now carefully buries them). But it has found another thing to explode, and something it does regularly: project budgets.

We keep saying this, but they’ve done it again. The latest cost estimate for the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening project has burgeoned to $1.9 billion. This is the third reported cost-overrun since the project was first approved in 2017—and the agency has yet to break ground.

The I-5 Rose Quarter project was sold to the Legislature in 2017 as having a price tag of $450 million; that jumped to $795 million in 2019, $1.45 billion in 2021, and now to as much as $1.9 billion. And if you read the bureaucratic tea leaves right, they’re likely to have an another jump in project costs a year or two from now.

Dead project walking

It doesn’t really matter how much the project costs, because the agency now concedes that it effectively doesn’t have any money to pay for actually building it. ODOT diverted most of the original $450 million provided by the Legislature to build another project (the I-205 Abernethy Bridge). The Governor and Legislature have put tolling plans on hold, and the agency’s revenue is falling, it is cutting preservation and maintenance, and threatening to cut operations (like plowing roads in the winter). The best the agency can offer is the vain hope that some new and undiscovered source of federal or state funds will magically appear sometime in the next few years. The agency has already spent $114 million on planning and engineering to get the project to the “30 percent” level of design, and says it would need an additional $100 to $140 million to complete plans and acquire right of way, and a further $1.2 to $1.6 billion to actually build something. As the Commission’s Chair lamented at its June 28, 2023 meeting “We’re out of money”.—None of this money is currently identified in ODOT’s budget. In theory, it might be possible to use future toll revenue to pay a portion of the cost of the project, but ODOT simply hasn’t done the needed financial homework, and has repeatedly said during the environmental review process that tolling is not “reaasonably foreseeable” for this project.

And ODOT’s own consultants have said tolling this stretch of I-5 would actually eliminate the need to widen the freeway at all. The Rose Quarter project is looking more and more like the 21st Century version of ODOT’s exploding whale.

Is it time to pull the plug on this project?

Less than two years ago, in September 2021, when the price was a mere $1.45 billion, OTC Commissioners questioned whether the Rose Quarter made any sense at all. Every dollar spent on this barely 1.5 mile long freeway widening project is a dollar that isn’t available to maintain or improve roads elsewhere in the state, and as we’ve noted, bonding grants this project an irrevocable priority for state and federal funds. Back then, according to the Oregon Public Broadcasting, Commissioner Sharon Smith argued:

Smith questioned the overall viability of the project and asked her colleagues whether they believe Oregonians would approve the project if it were put on the ballot.

“Do you want to spend $1.5 billion on a road project? Is that the best use of our public funds right now? And I don’t know if the answer would be yes,” she said.

Two years later, and the cost has risen to $1.9 billion, and yet Commissioner Smith—now chair of the Commission—is still waving the project forward. Just prior to the vote approving the staff’s plan she said:

“. . . we did make a commitment to the Rose Quarter and I’m not willing to back off of that. Unfortunately we do have a different plan than when we first started into it and the cost is astronomical—we need to figure a way of doing it.”

OTC Meeting Transcript. June 28, 2023

Time and again, as the agency they nominally supervise has blown through its previous budget estimates, the Oregon Transportation Commission has simply acquiesced and said “Ole’!” At least when it came to disposing of whale carcasses ODOT learned from its mistakes.

Cost Overruns: ODOT’s Reign of Error

To some, a cost increase of this magnitude may seem like an aberration. For anyone who has followed ODOT closely, it’s apparent this is very, very common. Over the past decade and a half at least, ODOT has blown through the budget estimates of virtually every large project they’ve undertaken.

ODOT has consistently underestimated the cost to complete its major highway projects. A review of ODOTs own reports for the largest projects its undertaken in the past 20 years shows a consistent pattern of cost overruns, as summarized here:

There’s abundant academic evidence about the consistent tendency of “megaprojects” to overrun early cost estimates. Bengt Flyvberg has literally written a book about it. The problem isn’t unique to Oregon. Two of the biggest bridge projects nationally (rebuilding the Tappan Zee Bridge N. of NYC, and SF’s Bay Bridge West Span both produced colossal overruns).

No Accountability for Overruns

There have been furtive efforts to oversee ODOT. In November 2015, Governor Brown said she was commissioning an performance management audit of ODOT.

ODOT did nothing for the first five months of 2016, and said the project would cost as much as half a million dollars. Initially, ODOT awarded a $350,000 oversight contract to an insider, who as it turns out, was angling for then ODOT director Matt Garrett’s job. .

After this conflict-of-interest was exposed, the department rescinded the contract in instead gave a million dollar contract to McKinsey & Co, (so without irony, ODOT had at least a 100 percent cost overrun on the contract to do their audit.)

And what McKinsey produced amounted to a whitewash, as I explained at Bike Portland. The audit covered up a long series of ODOT cost overruns, and instead focused on a long series of meaningless measures of internal administrative processes, such as the average time needed to process purchase orders. Meanwhile, the state’s million dollar auditors excluded from their cost overrun calculations the US20 Pioneer Mountain-Eddyville project, the single most expensive project that ODOT had undertaken, and even though excluding it, managed to understate and mis-label the 300 percent cost-overrun.

The final report from McKinsey recommended that ODOT could become more efficient by giving more money to consultants like McKinsey (as humorist Dave Barry would say “I’m not making this up.”)

Which, in a way, brings us full circle: Dave Barry was one of those principally responsible for popularizing the exploding whale story. With ODOT, the explosions just keep coming, but now they’re confined mostly destroying project budgets, rather than raining blubber. At least with whales, ODOT learned from its mistakes. When it comes to massive cost overruns, it’s simply become the way this agency does business. We give the last word to Barry, who narrates the whale explosion:

So they moved the spectators back up the beach, put a half-ton of dynamite next to the whale and set it off. I am probably not guilty of understatement when I say that what follows, on the videotape, is the most wonderful event in the history of the universe. First you see the whale carcass disappear in a huge blast of smoke and flame. Then you hear the happy spectators shouting “Yayy!” and “Whee!” Then, suddenly, the crowd’s tone changes. You hear a new sound like “splud.” You hear a woman’s voice shouting “Here come pieces of… MY GOD!” Something smears the camera lens.