What City Observatory did this week

We have an in-depth series of reports on the Oregon Department of Transportation’s imploding I-5 Rose Quarter freeway widening project.

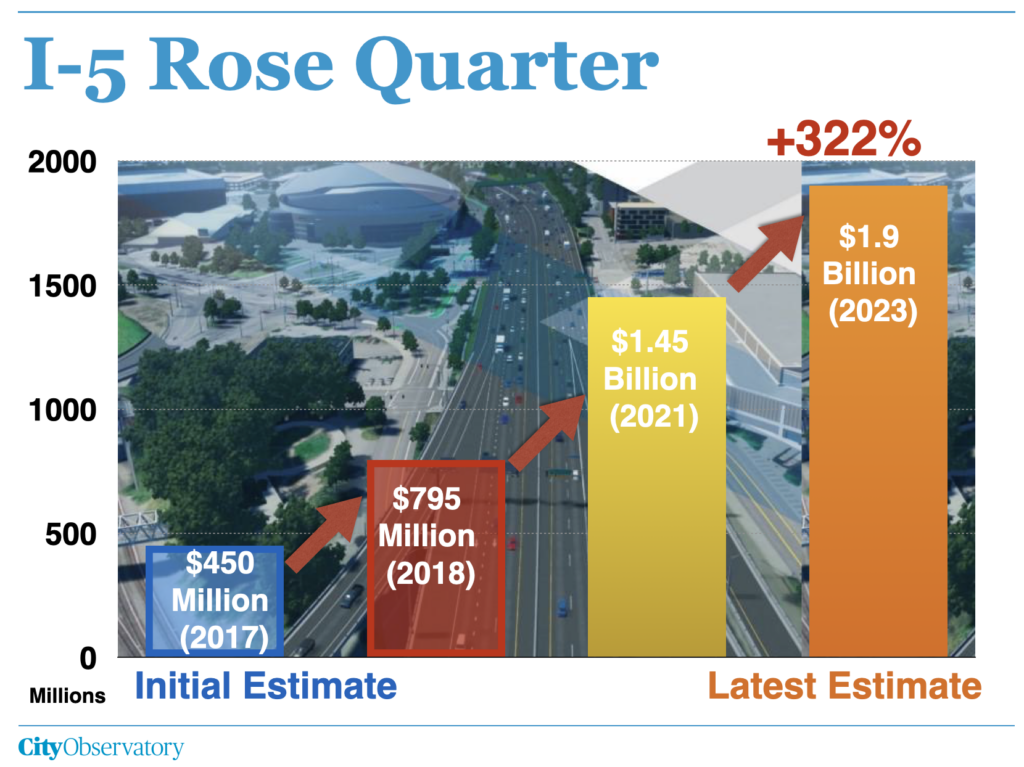

The cost of the I-5 Rose Quarter project has now quadrupled to $1.9 billion—it was a mere $450 million when it was sold to the Legislature in 2017.

ODOT hasn’t admitted its Rose Quarter project is actually dead, even though it has a $1.7 billion funding shortfall. Instead, the agency is playing a game called “Extend and pretend“—spending $40 to $60 million over the next two years to advance design work on the main part of the project to 30 percent completion, in hopes that someone will magically provide the needed funding.

Despite the project’s ballooning price-tag, ODOT officials claim its too late to do anything to reduce the size, scope or cost of the project, claiming they’ve reached a “pens down” moment. That’s factually untrue: the agency is still in the throes of designing the project, and just released yet another previously un-seen design concept including a new flyover ramp last month. Nothing in federal regulations precludes “right-sizing” the project even after funding and initial environmental approvals are received: that’s exactly what FHWA allowed with Cincinnati’s Brent Spence Bridge which was just sliced by about 40 percent in size and cost. Finally, federal regulations prohibit environmental approvals for projects that don’t have “reasonably available funding” and the Rose Quarter is nowhere close to that standard, by ODOT’s own admission.

The apparent collapse of the Rose Quarter project has angered many in Portland’s Black community, who were promised the project would somehow help restore the neighborhood devastated by the original freeway construction, as well as providing a bonanza of jobs and contracting opportunities for the community. Instead, ODOT took $450 million originally earmarked for the Rose Quarter project and diverted it to paying for the I-205 Abernethy Bridge, in suburban (and vastly whiter) West Linn Oregon. ODOT’s even signed contracts and started construction on this project, and its cost has now increased to $622 million.

Must Read

Freeways and the damage done: don’t just acknowledge, change. Transportation for America has a powerful new report—Divided by Design—on the damage that freeways have done to the nation’s cities, and the policy changes that need to be made to repair that harm, and prevent further destruction. Case studies of Washington and Atlanta show how urban freeways have decimated neighborhoods, displaced people–especially people of color–and harmed local budgets. Lately, its become fashionable for highway agencies to publicly acknowledge this harm; but most of that acknowledgement is purely rhetorical and performative, because the same agencies, including the US DOT are doubling down on their historic mistakes by pumping more billions into the same failed policies and projects. The Transportation for America reports decries this duplicity:

[Federal and state leaders] intent to do things differently or better than their publicly racist forebears in the 1950s and 1960s is irrelevant when many of those previous practices are still deeply embedded in the transportation policies and standards of today. Today’s leaders must understand how the past is still shaping current practices. They must reevaluate how their decisions are made and who their decisions serve. Congress and the federal government are right in part: it is time to fix the harms of our transportation system, but creating tiny new programs will fail to address the damage.

Transportation for America has a series of specific, substantive recommendations for addressing and correcting the inequities woven into the current structure of transportation policy in the US.

Utah’s smart road usage charge experiment. Kea Wilson at Streetsblog reports on Utah’s application of the latest technology to road use charging. It’s increasingly apparent that the gas tax is in terminal decline as a way to pay for roads, and state and federal governments are scrambling to come up with an alternative. The choice is likely to come down to some kind of VMT (vehicle mile traveled) fee, but the big policy question is whether it will be a smart fee, or a dumb one. The simple minded approach is to charge a flat fee per mile, but not all vehicles and not all miles are created equal. Providing capacity for travel at peak hours is much more expensive, as is accommodating heavier, more dangerous and more highly polluting vehicles. Utah’s monitoring system provided by technology startup ClearRoad allows road user fees to vary by vehicle, by time of date, and by road traveled. Utah is testing

a new GPS-equipped dongle that will not just monitor how much motorists drive, but exactly where they do it, down the specific lane on the highway they choose. Then, communities can consolidate that data into a single road usage charge that can be automatically adjusted based on their unique priorities — think extra tolls for using the express lane, or graduated fees for low-income motorists who truly have to drive — and automatically distributed to the agencies that manage the exact roadways those drivers’ actually traveled.

We get one chance a century to change the way we pay for transportation: we need to get this right. Smart technology can enable a smart choice.

In the news

City Observatory Director Joe Cortright was named one of the 100 Most Influential Urbanists, Past and Present in a poll conducted by Planetizen.