What City Observatory did this week

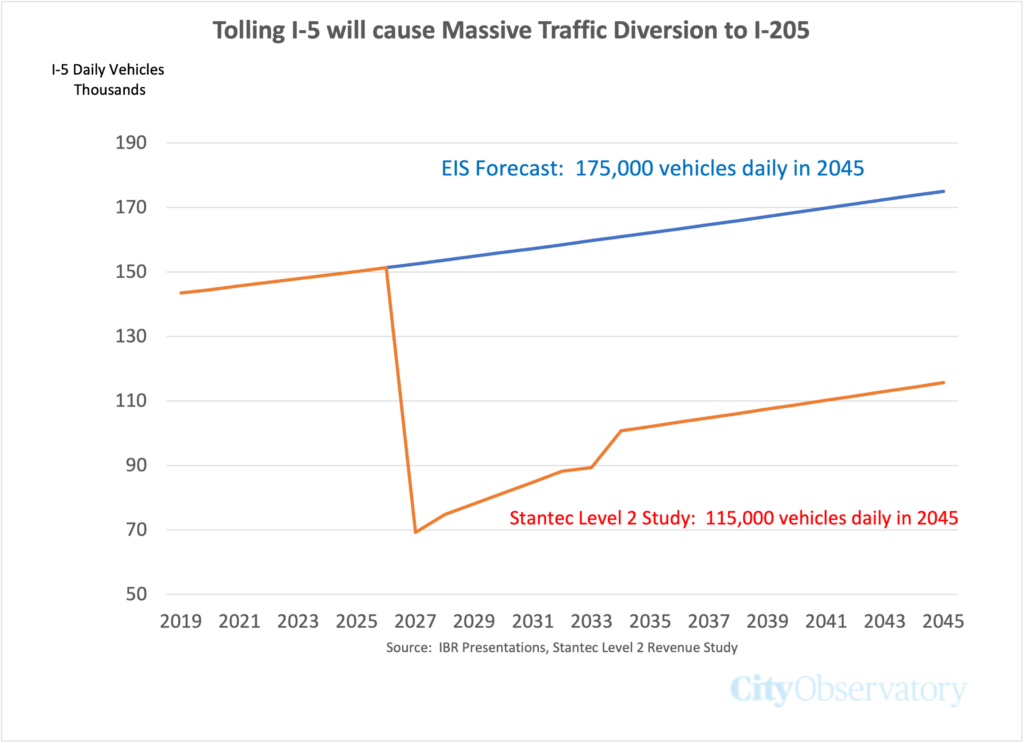

Tolling i-5 will produce massive traffic diversion. The proposed I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement (IBR) Project will be paid for in part by $2.80 to $4.30 tolls charged to travelers. These tolls will cause tens of thousands of vehicles per day to stop crossing the I-5 bridge; and most traffic will divert to the parallel I-205 bridge, producing gridlock, according to IBR consultant reports and Metro travel demand modeling.

OregonDOT and Washington State DOT officials have offered vague and largely meaningless claims about potential diversion from tolling the I-5 bridge, and failed to disclose actual analyses done this subject by their consultants.

City Observatory obtained—via public records requests—toll revenue estimates prepared by IBR contractor Stantec, and travel demand modeling prepared by Metro for the IBR project. These studies show that tolling I-5 will dramatically reduce I-5 traffic, with most vehicles diverting to I-205.

- Tolling I-5 will cause traffic levels on I-5, currently about 140,000 vehicles per day will fall by almost half, and will permanently depress I-5 traffic

- Tolling I-5 will cause more than 30,000 vehicles to divert to the parallel Interstate 205 bridge, likely producing gridlock.

The new toll revenue projections echo exactly the findings of studies for the earlier carbon copy of this same project (then called the Columbia River Crossing) as well as the experience of tolled bridges and highways elsewhere in the country.

Highway agency claims that investment grade forecasts are unlikely “worst case scenarios” are untrue: Traffic levels routinely fall below levels predicted in investment grade forecasts, as happened with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, and many other similar projects.

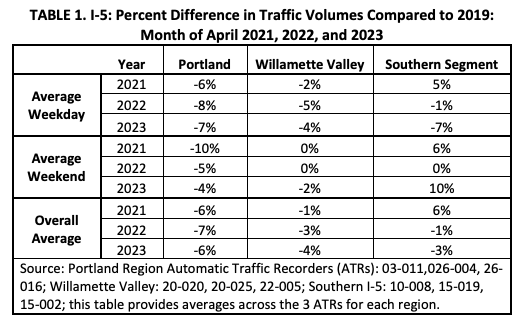

Down is not up: The truth about traffic, congestion and trucking. A central message of the highway building sales pitch is that traffic is ever-growing and ever worsening, and that we have no choice but to throw more money at expanded capacity. The Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) claims that traffic is every-rising, congestion is ever-worsening, and we’re always moving more and more trucks. The reality, as revealed by ODOT’s own statistics is very different:

Post-pandemic, traffic levels are lower than before, time lost to traffic congestion is down almost 40 percent, and fewer trucks are on Oregon’s roads. This lower level of demand means we don’t need to squander billions on added capacity, as ODOT is proposing. Instead, measures to reduce or manage demand, like congestion pricing, could give us much faster travel times, at far lower cost. Claims that the increase in traffic is inexorable, and that congestion will only get worse, are just a marketing gimmick to sell capacity expansion. It speaks volumes about state highway agencies that they’ll willing distort what their own actual data are showing about declining traffic, lessened congestion, and fewer trucks on the road, to make these spurious claims.

Must Read

Like the “End of History” proclamations the “End of Freeways are premature and misleading. Joe Linton, writing at LA Streetsblog dismantles some phony greenwashing from highway builders in Southern California who’ve billed the opening of a $2.1 billion freeway expansion project as the very last freeway they’ll ever build. The CalTrans talking point, offered up stenographically by the Los Angeles Times, is that the completion of the 405 freeway in Orange County marks the end of an era.

As Linton points out, that’s not true: The region’s highway agencies are planning literally billions in more spending on dozens of freeway projects. Not only that, but the phony claim that “its the end of an era” is exactly the same story CalTrans got placed in a New York Times story—thirty years ago.

But the freeway era didn’t come anywhere near ending in the 1990s. Caltrans continued to spend copious state and federal funding to expand highways. Countywide sales taxes in Los Angeles and Orange counties funneled even more money into the well-oiled machine that continued to tear down homes to add more and more lanes. Since the 1990s, Caltrans leaders give lip service to their agency turning over a new leaf, but the department’s massive car capacity projects show these pledges to be false.

To be sure, they’ll keep building (and widening) freeways, they just won’t call them that. It will be “auxiliary lanes” and “repaving.” CalTrans just fired its deputy director for calling out the illegal and sham use of “repaving” as cover for widening Interstate 80 between Sacramento and Davis. These are people who will nod and murmur that we can’t build our way out of congestion–and then spend billions more widening roads. It’s hypcritical greenwash.

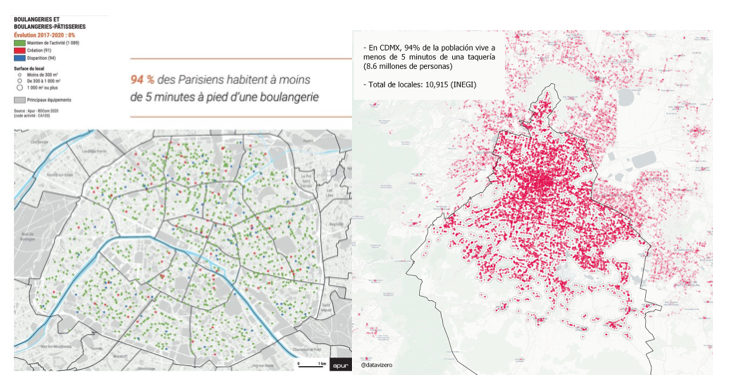

Accessibility: Our daily bread. Cities solve for transportation not just with buses, bikes and cars, but with proximity. If daily destinations are close at hand, it takes less transport expense and infrastructure just to live. In economic terms, transportation is a “transaction cost”–the more and further we have to travel, the more time and money we have to spend to do the basics. What good cities do is to put critical destinations close to where we live. Dueling maps appeared on social media this past week that illustrate this pattern. In Paris, Jonathan Berk (@berkie1) shows that 94 percent of Parisians live within 5 minutes of a boulangerie. Not to be outdone, @datavizero offers up a map showing that 95 percent of residents of Mexico City are within 5 minutes of a taqueria.

The enormous savings from convenience, proximity and choice that are present in great cities are often entirely overlooked in our economic reckoning. Next time someone talks about transportation, please think about how long it takes a typical resident to get a baguette or a taco.