What City Observatory this week

1. The Urban Institute gets inclusion backwards. The Urban Institute has released an updated set of estimates that purport to measure which US cities are the most inclusive. The report is conceptually flawed, and actually gets its conclusions backwards, classifying some of the nation’s most exclusive places as “inclusive.” Highly equal cities are almost always either exclusive suburban enclaves (that achieve homogeneity by rigid zoning limits that exclude the poor) or impoverished cities that have been abandoned by upper and middle income households, leaving them homogeneous but poor. (For example, many of Urban’s Institute’s “most inclusive cities” are suburbs like Bellevue, Naperville and Santa Clara–among the wealthiest 20 cities in the US; while Detroit and Cleveland are also highly ranked for inclusiveness. Small geographies, neighborhoods/cities that have high levels of measured income inequality (90/10 ratio, Gini Index) are generally much more inclusive than comparable geographies that with lower levels of measured inequality. Rich and poor living closer together produces more measured inequality, but also means greater inclusion.

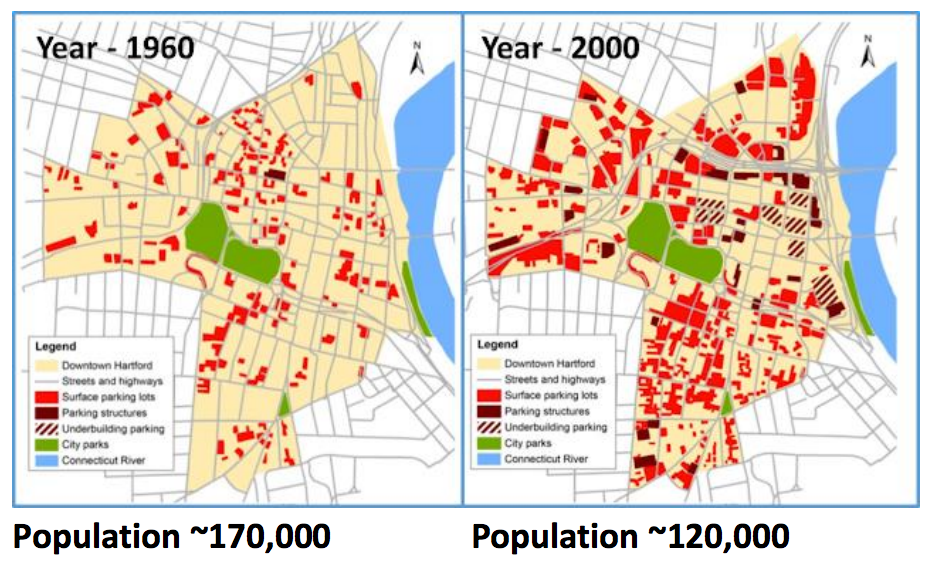

2. Parking should pay its way: Hartford’s land value tax lite. One of the perverse effects of the US system of property taxation is that improving urban property, by say building apartments, offices or stores, triggers an increase in tax liability. That tends to discourage development and reward low value uses of valuable urban land. Effectively the biggest subsidies from this arrangement go to surface parking lots, which usually pay taxes only on the value of land. While in theory a land-value tax would fix this incentive problem, its politically hard to change the whole tax system. Hartford, Connecticut has a proposal to up fees on parking lots by a modest amount (about 50 cents per space per day) to fund transportation. The fee would work like a kind of land value tax “lite.” This is definitely a step toward making the tax system fairer; as parking lots don’t pay anything close to their full-freight in local finance. Take for example stormwater: Hartford’s building a multi-billion dollar subway for sewage, largely to deal with the runoff from roads and parking lots. City water users pay the full cost of this project; cars and parking lots pay nothing for a problem they largely create. More cities should look into asking parking to pay its way.

Must read

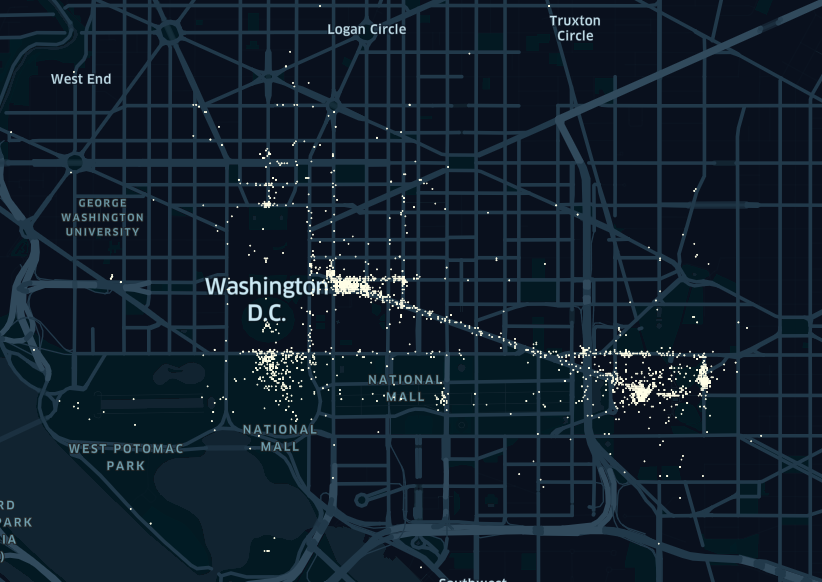

1. The geography of sedition: Geolocation of Parler Videos, 6 January 2021.

2. A roundup of what’s been written about Covid-19 and cities. At City Observatory, we’ve spent a good deal of time tracking data on the Coronavirus pandemic as it spread, paying particular attention to a couple of themes, one linking density to the virus, something which appeared as a popular theory early on, but which must now deal with higher rates of death in rural areas. A second theme looks at the future of urban areas in an era of work-at-home for many professionals. James Brasuell at Planetizen has compiled a comprehensive list of news articles and blog posts on these themes; it’s a useful resource for following the debate.

3. Todd Litman: Housing first, cars last. Leave it to one-man transportation think tank Todd LItman to succinctly make lay out the definitive strategy for advancing equitable urbanism. In an essay at Planetizen, Litman writes:

Our current laws do not mandate housing for people, but virtually all jurisdictions do mandate an abundant and costly supply of housing for motor vehicles. Our zoning codes require that most buildings include numerous parking spaces that are generally unpriced, which is a huge and unfair subsidy for automobile use. This increases housing costs, encourages driving, and forces car-free households to pay for expensive parking facilities they don’t need.

There’s a shortage of affordable housing nearly everywhere, particularly in some of our most livable cities. But at the same time, we’re awash in “free” (meaning un-priced) parking, with three or four or more parking spaces for every car in most metro areas. Indeed, parking requirements essentially tax housing to subsidize parking. Reversing this fundamentally wrong-headed prioritization is the key to building better and more equitable cities.

4. How Covid-19 debunked one old gentrification myth. Jake Ambinder, writing in the Atlantic. One of the most resilient folk narratives of gentrification is the idea that by building more housing greedy developers drive up rents and cause displacement. Not only has that theory never made much sense, and has been disproven by repeated studies, but the deflation of demand in some previously super-heated urban markets shows that when demand and supply are in closer balance, rents actually come down. The real cause of the affordability crisis in thriving metro areas isn’t the developers, but the constraints on development fomented and defended by NIMBY homeowners. The prevalence of single-family zoning and widespread apartment bans wrought by nominally pro-environment homeowner groups constrict housing supply, drive up rents, and trigger displacement. As Ambinder concludes:

The homeowner-friendly slow-growth activism that marked American cities in the late twentieth century is thus best understood not as the predecessor of today’s anti-gentrification politics but as the progenitor of the gentrification crisis itself. In wealthy coastal cities today, one need not develop skyscrapers or shopping malls to be a speculator in urban property. With widespread housing scarcity, simply owning a modest home in Berkeley or Brooklyn will suffice.