What City Observatory this week

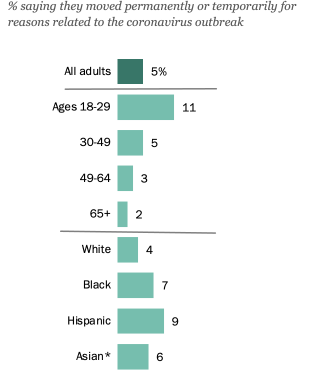

1. Covid migration: Disproportionately young, economically stressed and people of color. Data shows the moves prompted by Covid-19 are more reflective of economic distress for the vulnerable than a reordering of urban location preferences of older professionals. A new survey from the Pew Research Center shines a bright light on the actual volume and motivation of migration in the pandemic era. We highlight some of the findings. Notably, there’s relatively little migration in the wake of Covid-19. Most Covid-related migration is temporary, involves moving in with friends or relatives, and not leaving a metro area. It’s also not professionals fleeing cities: Covid-related movers tend to be young (many are students), and are prompted by economic distress

Pew’s data show that fewer than one in seven moves attributable to Covid-19 are “permanent” and that mover’s tend to be disproportionately persons of color.

2. Guest contributor Garlynn Woodsong returns with a follow on commentary suggesting an equitable carbon fee and dividend should be set to a price level necessary to achieve GHG reduction goals; kicker payment should be set so 70% of people receive a net income after paying carbon tax or at least break even. There’s an important lesson from our response to the pandemic: In the face of a shared crisis, it makes sense to provide generous financial support for those who have to adjust their lives and liveliehoods in order to tackle a big problem. A carbon dividend, financed by the proceeds of a carbon emissions fee would provide the wherewithal to help most people make needed changes to changes to their carbon footprint, and would offset the financial cost of the transition to those who couldn’t easily or quickly change.

Must read

1. To meet climate goals, think outside the electric car. Writing at Bloomberg CityLab, Transportation for America’s Beth Osborne, and Rocky Mountain Institute’s Ben Holland point out the limits of assuming that the problems of our auto-dominated transportation system can be met solely by electrifying cars. Cleaner cars will help, but it will take decades to replace the existing fleet, and the larger the number of cars, the harder it is to achieve our shared climate goals.

The truth is very simple: If we continue to design our communities and transportation systems to require more driving alone, even if it’s in an electric car, it makes decarbonization far harder. According to Rocky Mountain Institute’s analysis, the U.S. transportation sector needs to reduce carbon emissions 43 percent by 2030 in order to align with 1.5° C climate goals — requiring that we put 70 million EVs on the road and reduce per-capita vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by 20 percent in the next nine years. Even under the most ambitious EV adoption scenarios, we must still reduce driving.

2. People who leave San Francisco don’t go far. There’s a lot of hand-wringing that the rise of work-at-home means the death of San Francisco. While anecdotes about of CEOs and handfuls of professionals leaving the Bay Area for Texas or Florida, there’s been a lack of hard data on the subject. The San Francisco Chronicle reports that US Postal Service change-of-address filings show that out-migration from the City of San Francisco, while up in 2020, is mostly to other parts of the Bay Area and California.

City economist, Ted Egan reports that migration patterns follow a well-worn path with most movement to nearby suburbs. Few people are moving out of state, and according to the Chronicle, Egan argues that the fact they reside nearby could represent a post-pandemic “silver lining” for San Francisco:

“You are not going to have to worry about getting them to move back from Boise. It looks more like normal pre-COVID migration flows. People are settling in to nearby Bay Area suburbs. They are going to Sacramento and L.A. . . . Austin, Texas is way down the list, Portland is way down the list. New York is way down the list.”

3. How highways make traffic worse. This one is more of a “must watch”: Vox’s video explainer of why widening urban highways doesn’t reduce congestion. If you’re looking for a simple, graphic explanation of how induced demand works, you’ll want to watch—and share—this video. The video recites one of our favorite stories in this vein, the multi-billion dollar widening of Houston’s Katy Freeway, now North America’s widest—which spectacularly failed to reduce congestion. Within just a few years of the widening project being completed, commute times in this corridor were longer than ever. The freeway simply served to make the region even more sprawling, car-dependent and climate wrecking than before.

New Knowledge

This synopsis of six studies finds that the consensus is that the construction of market rate housing tends to make neighborhood housing more affordable than it would otherwise be. Five of the six studies conclude that market-rate housing makes nearby housing more affordable across all income levels of rental units; the sixth study finds mixed results with the affordability benefits confined to lower rents for higher end apartments.

In their conclusion, Phillips, Manville and Lens note that a principal reason for expanding market rate development in low income neighborhoods is the land use restrictions that effectively preclude more development in higher income areas. Because single family zoning and tortuous development approval processes make it impossible to build more market rate housing in established high income areas, the demand for these units spills over onto some low income communities, raising the affordability and gentrification concerns that fuel public debate:

. . . this whole discussion — of what happens when new development arrives in a neighborhood where many lower-income people live — could be largely avoided if we built new housing mostly in higher-income, higher-resourced communities. Development in more affluent places, where fewer residents are precariously housed, could allow more people access to opportunities and alleviate demand pressures elsewhere in a region. But such development rarely happens now, because zoning prevents it.

Tragically, it seems, that a frequent policy prescription is to make low income neighborhoods as potent in blocking new development as their high income peers, a kind of NIMBY-for-all solution that’s only likely to worsen price pressures and displacement across an entire market.

Shane Phillips, Michael Manville & Michael Lens, Research Roundup: The Effect of Market-Rate Development on Neighborhood Rents, UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Studies, February 17, 2021

In the News

UrbanTurf, a Washington, DC-based real estate information site pointed its readers to our analysis showing the connection between city segregation and the Black-white wealth gap.