There’s relatively little migration in the wake of Covid-19

Most Covid-related migration is temporary, involves moving in with friends or relatives, and not leaving a metro area

It’s not professionals fleeing cities: Covid-related movers tend to be young (many are students), and are prompted by economic distress

From the earliest days of the pandemic, pundits predicted that the Covid-19 virus would prompt rapid and permanent migration away from cities. First, it was the concern that city residents were somehow more susceptible to the Coronavirus—prompted by a weak correlation driven mainly by high infection rates in New York in the early days of the pandemic, but which completely reversed as rural areas now have higher rates of cases and deaths. Then the argument morphed: Now, thanks to Zoom and other web-technology, we can all work at home, so there’s no reason for companies to pay for expensive offices (or for workers to live in expensive cities). We think the pessimism about cities is massively overstated for at least seven reasons. In both cases, this theory has been fueled by anecdotes of highly paid professional workers de-camping from big cities to smaller cities, or rural ones.

But these anecdotes seriously mis-represent the nature and scale of migration. First, as we’ve noted earlier, migrants in these anecdotes don’t usually leave metro areas at all (many examples are people who were already considering a move to nearby suburbs), but even when they do leave a New York or a San Francisco, its for another, albeit smaller, tech center, like Seattle.

Many of these journalistic anecdotes suffer from what our friend Jarrett Walker calls “elite projection“: a tendency to view things from the perspective of the richest and most advantaged, rather from the average person. Early stories profiled Upper Eastside neighborhoods deserted by their residents harboring in the Hamptons or Adirondacks. That genre continues in the vaccine era, as well. Consider this gem from Bloomberg:

A new study sheds some light on who’s actually moving in the post-Covid world and why. It’s not so much mid-career professionals moving permanently; it’s really much more economically distressed younger adults, moving in (or back in) with family and friends; movers also disproportionately people of color.

Pew Research, which bills its work as that of a “fact tank” provides some insights into the actual extent, character and motivations of the Covid-induced movement. Their recent survey of 15,000 adults nationally included a battery of migration-related questions. They’ve shared some of the top-line results from the survey. Here are the highlights:

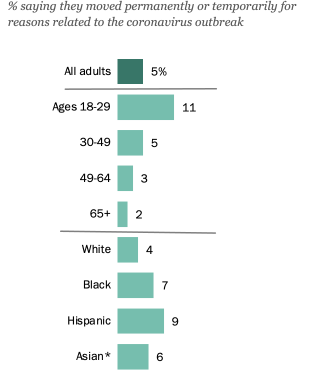

Not many people moved due to Covid. All in all about five percent of all Americans report having moved due to the Covid-19 pandemic and its related fallout. (Even that number is smaller than it seems, because it includes temporary moves. Of the 5 percent who reported moving due to concerns about Covid (or related economic problems), about one in six said their move was so permanent that they “bought or rented a new home on a long-term basis.” (Unhelpfully, the Pew migration question asks whether people moved either temporarily or permanently, but fails to define either of these terms. If a family spent a week or a weekend away from New York at the height of the pandemic outbreak in March, would the answer be yes?)

Economic reasons seem to dominate moves. Particularly in the past few months, it has been the economic hardship, rather than concern about the Covid-19 virus itself that seems to be prompting moves. Financial reasons, including job loss account for a third of all moves. The more common story is not moving to work remotely, but moving because one has no work.

The demographics: Young, Hispanic, and lower income. Overall, about 5 percent of Americans report either a temporary or permanent move, but 18-29 year olds are twice as likely as other Americans to report a move, Hispanics are nearly twice as likely. How many of the press accounts of Covid migration speak to twenty-something people of color moving back in with their family, because they’ve lost their job? That’s a far more representative migrant than the older, wealthier, mid-career professional who can afford to buy a new home and who’s so secure in their work that they can work at a distance.

Students and School Figure prominently. A significant amount of recorded moves seem to be students unable to attend school. That’s implied by the demographic data (those 18-29 are twice as likely to move), by the places they move to (a plurality of movers go to live with Mom, Dad or another relative), and by the direct answer to the question about why people move: About one in seven who reported moving due to Covid through November said it was because their college campus or school had closed.

Few people cite more space or remote work as a motivation. While the narrative about taking advantage of remote work to get a bigger home, and “zoom it in” figures prominently in journalistic accounts, it’s rare according to the survey. Pew reports:

. . . people who moved due to the virus said the main reason was that they needed more space (2%) or were able to work remotely (1%).

None of these survey results seem to provide strong evidence for a re-ordering of America’s locational preferences in the wake of Covid. The fact that most moves are among young adults with lower incomes, suggests it’s not the higher income, mid- to late-career professionals abandoning cities for suburbs or rural areas that accounts for much of the reported migration. Whether in the midst of the pandemic’s rising caseload, or waiting impatiently for the vaccine roll-out, it’s easy to make overblown predictions about urban flight. Cities have long weathered such crises, and rebounded in their wake. They will again.