What City Observatory did this week

A note to City Observatory readers: We’re deep in the thick of Portland’s debate about whether to spend a half billion dollars to widen a mile-long stretch of freeway near the city’s downtown. Based on all we’ve learned in our research at City Observatory, and our analysis of the project, we think its a signal example of the application of failed highway engineering practices that are likely to seriously damage a rebounding neighborhood in a thriving city. We think there are broad lessons for cities around the country, and so this week and next, we’ll be devoting most of our coverage to an in-depth examination of the project and its implications. Our regularly scheduled Week Observed features, “Must Read” and “New Knowledge” will return in two weeks.

1. The case against freeway widening. We and others have written extensively about the effects of freeways on cities, and on this project in particular. We’ve boiled that down to a single guide-posted commentary that outlines each of the distinct arguments against freeways, ranging from induced demand, to safety, to climate concerns, to neighborhood impacts, to the project’s financial consequences. We’ll be updating this one-stop guide to the freeway fight in the coming weeks.

2. Hidden in a black box. The Oregon Department of Transportation makes a remarkable claim for its freeway widening project: that unlike virtually every freeway widening in a major city anywhere, it will speed traffic but not create induced demand. In addition, they argue that somehow it will result in lower carbon emissions. Both those claims fly in the face of a consistent and well-understood literature about induced demand, one that is so-well established that its now referred to as “the fundamental law of road congestion.” What’s missing from this transportation miracle, though, is any actual documentation as to how traffic and emission models were constructed to generate these results. What assumptions were made? It’s almost impossible to know. Take one example: the project’s “Traffic Technical Report” contains absolutely no references to the average daily traffic levels (ADT), which are the single most common yardstick for measuring traffic (and calculating congestion and emissions). A traffic report without ADT is as useless as a financial report with no dollar amounts. This willful hiding of the facts in the face of some outlandish claims about project results puts the public and decision-makers behind the eight-ball.

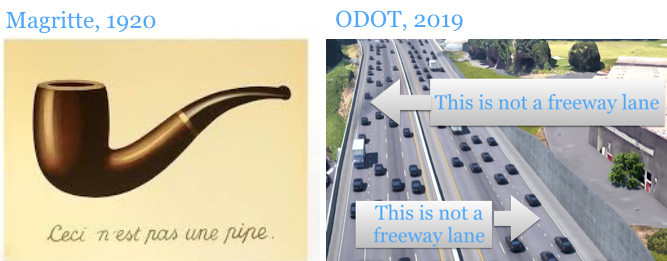

3. Using Orwellian double-speak to sell freeways. To hear the Oregon Department of Transportation tell it, they’re half-billion dollar project doesn’t actually widen the I-5 freeway at all. That’s because they’re not adding “freeway lanes” but are instead adding “auxiliary lanes.” No matter what you call them, this stretch of freeway is going to get more lanes, and it’s the expanded capacity and freer movement that will induce additional traffic, not what the agency decides to call them. It borders on the surreal: Just as Magritte told us that it wasn’t a pipe, so to does ODOT tells us that theirs are not freeway lanes. ODOT also insists on calling it an “Improvement” project, a tactic that staff of the neighboring Washington Department of Transportation has specifically branded as deceptive and misleading. It turns out that this particular rhetorical device has a long history in Portland, Robert Moses (yes, that Robert Moses) came to Portland in 1943, sketched out a freeway grid for the city (thankfully, mostly not built, save for this stretch) and insisted that his plan be called “Portland Improvement.”

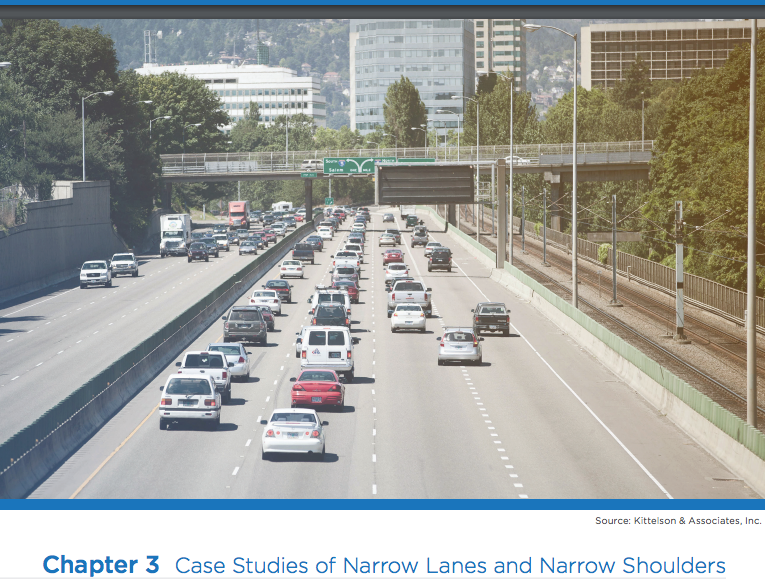

4. Engineering an eight-lane freeway. As noted above, there’s a huge amount of public relations spin being devoted to denying that this project has anything to do with a wider freeway. But rather than debate how we count lanes, or what we call them, it’s much more illuminating to look at the road space and structures ODOT is proposing to build. It’s hidden away in an appendix of the Environmental Assessment, in the fine print in a single figure, but the agency is planning to build a right-of-way that is 126-feet wide. With standard 12-foot lanes, and the kind of shoulders widths ODOT regularly uses in Portland-area Interstate freeways (including I-84, just a few hundred meters from this project), that 126-foot right of way will hold a full eight-lane freeway, with four foot-inside shoulders, and seven foot outside shoulders. Once the project is built, it would take a few hours work with a paint truck to turn this into an eight-lane freeway. ODOT has been intentionally deceptive about the number of lanes it engineers before; in 2010, despite direction to reduce the proposed Columbia River Crossing from 12 lanes to 10, the agency simply edited all its project documents to say “ten lanes,” and also disappeared all published references to the physical width of the bridge it would build–and carried on to build the same twin 90-foot wide bridges it engineered to carry 12 lanes in the first place.

5. Distorted images: What highway department renderings reveal and conceal about impacts on bikes and pedestrians. A major selling point of the “improvement” project is a claim that it will make things better for those who walk and bike in the area. The project’s got a series of carefully-crafted computer-generated renderings that attempt to highlight these features. But if you look closely, you’ll see that there are a range of bike- and pedestrian-hostile aspects: a central feature of the project is miniature diverging diamond interchange, in which car traffic runs on the left side of the roadway. In addition, while Portland, like many cities has been installing curb extensions, to shorten pedestrian crossing distances and slow car traffic, this project actually cuts away the corners of blocks, to create higher speed turning lanes–exactly the feature that endangers pedestrians. In addition, the renderings are constructed to put bikes and pedestrians in the foreground (making them appear larger and more prominent) while putting cars in the background (making them seem small and insignificant). And speaking of cars, in this crowded intersection, ODOT shows only 5 automobiles, in contrast to 25 pedestrians. That turns out to be a 200-fold visual lie: city traffic counts show cars actually outnumber pedestrians here more than 40 to one. The renderings also insert wireframes of non-existent buildings to make the site seem more interesting and urban.

In the News

1. Oregon Public Broadcasting summarized the outpouring of community opposition to the freeway widening project at this week’s public hearing in Jeff Mapes’ story, “Opponents Dominate Hearing On Portland Rose Quarter I-5 Expansion Project.”

2. The Oregonian’s Andrew Theen summarized City Observatory’s examination of the freeway widening project in a story entitled “Portland economist calls Rose Quarter Freeway project ‘tragic error.’

3. StrongTowns published our analysis of the deceptive and at times surreal rhetorical devices that Oregon’s Department of Transportation is using to sell it’s proposed freeway widening project.