What City Observatory did this week

1. The limits of our current approaches to providing affordable housing. We present a summary of some remarks offered by Rob Stewart, a principal with JBG Smith Real Estate, reflecting on his experience working on housing issues in Washington DC. Broadly speaking, there are two ways we tend to go about encouraging more housing affordability: the supply side approach of encouraging the market to build more housing, and the subsidized housing approach, offering tax credits and other support for the construction of new, purpose built, rent-restricted housing. In practice, our current systems of subsidizing affordable housing produce relatively few units (because new construction is so expensive) and also have tended to reinforce existing patterns of economic segregation (because new units get built in or near high poverty neighborhoods).

2. A third way approach to addressing housing affordability and integration. We explore a new proposal from the Washington Housing Initiative to combine private and public (or philanthropic) capital to buy existing apartments and maintain their affordability for low and moderate income families. By buying units in the likely path of revitalization, the plan can maintain affordability in exactly the kind of neighborhoods that are likely to offer greater opportunities for low and moderate income households. In addition, this strategy would break the tendency of existing subsidized housing programs to perpetuate patterns of economic segregation.

3. Dangerous by Design. It’s a very well-researched annual report, but it’s a grim one: Smart Growth America has once again tabulated the toll that our nation’s transportation system takes on pedestrians. In the past decade, more than 5,000 Americans have been killed while walking on the nation’s streets and roads. While the death toll for those in cars has gone down, the toll for pedestrians is up sharply. More importantly, the patterns of deaths are neither random nor accidental: sprawling metro areas with car-dependent travel systems have consistently higher pedestrian death tolls. More driving means more dying. Higher-speed multi-lane arterials are a particular menace to pedestrians.

4. Happy Groundhog’s Day’s Oregon: You’re stuck in a loop on climate. Groundhog’s day is coming up again, and we take our usual annual look at how Oregon is doing in achieving its legally adopted goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to a fraction of their 1990 levels. Pledging allegiance to the goal is a standard feature of local politician’s Earth Day messages, but as in year’s past, progress is sadly lacking. The state’s Greenhouse Gas Commission reports that while the state has made some progress in reducing powerplant and industrial emissions, carbon from transportation continues to increase, and there’s essentially no way the state will ever reach its carbon reduction goals.

Must read

1. Oregon homebuilders question legalizing missing middle housing. Here’s a great story from our own backyard, reported by the Daily Journal of Commerce‘s Chuck Slothower and brought to wide attention by Iain MacKenzie of NextPortland. Oregon House Speaker Tina Kotek has introduced legislation to legalize duplex, triplex and fourplex housing in residential zones in larger cities in Oregon. You’d think that a group that builds homes, and purports to oppose regulation we be on board with this. Not so much: Oregon Home Builders Association says they’re worried that the bill will undercut the case they’re trying to make for expanding urban growth boundaries to allow more low density housing on the periphery of metropolitan areas. That’s pretty cynical, to be sure, and shows that despite their name, the organization may not really be interested in seeing more homes built. In addition, it undercuts the oft-repeated claim that consumers “prefer” suburban living: if the only way to sell more suburban houses is to block the construction of more housing in urban centers, that’s a pretty good indication that the only reason many consumers bought suburban single-family homes was because they had been denied the opportunity to purchase an affordable duplex, triplex or fourplex home.

2. How to fix congestion in Manhattan in five easy steps. The advent of ride-hailed vehicles has pushed New York City’s streets to the limit of what they can handle if traffic isn’t priced in some fashion. In testimony to the New York City Council, Charles Komanoff outlines a five point plan for applying congestion to Manhattan. The key: levelling the playing field among taxis, ride-hailed vehicles and privately owned cars. He proposes that rather than single out some modes for surcharges (like the ones imposed on ride-hailing) that all vehicles should pay for using congested city streets in Manhattan. Ride-hailed vehicles and taxis would pay per minute for their time in the center, while private vehicles would pay a cordon charge to enter. And to encourage greater efficiency by Uber and Lyft, Komanoff would add a surcharge for cruising city streets looking or waiting for fares. Komanoff’s modeling suggests this plan would increase traffic speeds and reduce congestion and raise about $1.7 billion annually to support the city’s struggling transit system.

3. Congestion pricing and the green dividend in Boston. The City of Boston’s Green Ribbon Commission has just released its report, recommending that in addition to electrifying buildings throughout the city (to enable them to use wind and solar power for heating and cooling), that the city should implement some form of congestion pricing, to reduce automobile use and encourage mass transit, walking and cycling. The plan also recognizes that higher urban densities would facilitate this shift and specifically urges the city to upzone urban neighborhoods. The task force also calculated a shift to greener, denser living would save Bostonians $600 million per year by 2050, through lower energy bills, a classic example of what we call the green dividend. (A hat tip to Curbed Boston).

New Knowledge

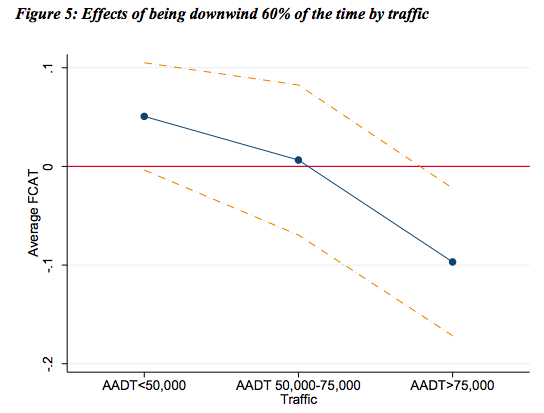

Pollution from cars and trucks lowers student performance in schools near highways. For decades, we’ve know about the negative health effects of air pollution, but a new economic study shows that air pollution imposes a significant cognitive cost on young learners. This study looked at the correlation between air pollution levels near schools and the academic performance of students in those schools. It found that students attending schools located near and downwind from busy highways had lower rates of academic performance, higher absenteeism and higher rates of disciplinary problems than those attending less polluted schools. The more traffic on nearby roads, the larger the decline in scores on state standardized tests.

The study use a sophisticated methodology to tease out the effects of school level pollution, looking at students who moved between schools. They conclude:

. . . children who move to a school downwind of a major highway have lower test scores and a higher likelihood of behavioral incidents and missing school than when those same children attended schools with similar characteristics that were not downwind of a major highway. The effects are larger for more heavily-trafficked roads, and the effects appear to last even after the child moves away from a downwind school. This suggests that once damage from pollution is done, even during middle childhood, it might persist, potentially affecting outcomes far into the future.

Jennifer Heissel, Claudia Persico, David Simon, Does pollution drive achievement? The effect of traffic pollution on academic performance. NBER Working Paper No. 25489.