If OregonDOT is serious about “restorative justice” it should mitigate highway damage by building housing

Around the country, states are subsidizing affordable housing to mitigate the damage done by highway projects

Mitigation is part of NEPA requirements and complying with federal Environmental Justice policy

The construction of urban highways has devastating effects on nearby neighborhoods. Not only has building highways directly led to housing demolitions to provide space for roadways, the surge of traffic typically undermines the desirability of nearby homes and neighborhoods, leading to the depreciation of home values, the decline of neighborhood economic health, and population out-migration. That story has been told numerous times across the US; we’ve detailed how the Oregon Department of Transportation’s decisions to build three huge highway projects in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s decimated Portland’s Albina neighborhood. This predominantly Black neighborhood lost two-thirds of its population over the course of a little more than two decades. At the time, no one gave much thought to the loss of hundreds or thousands of housing units, or the effect on these neighborhoods. But increasingly, state highway agencies are looking to mitigate the negative effect of current and past highway construction by subsidizing housing in affected neighborhoods. Here are three examples from around the country.

The Oregon Department of Transportation claims that it is interested in “restorative justice” for the Albina community, which has identified housing as one of the keys to building wealth and restoring the neighborhood. And ODOT’s project illustrations show how hundreds of housing units might be built near the project–but these are just vaporaware, as ODOT hasn’t committed to spending a dime of its money to making that happen, to replacing the homes it demolished over the decades. Based on the past and current experience of other states, there’s no reason that they can’t treat investments in housing as mitigation, just as ODOT routinely spends a portion of its highway budget on restoring wildlife habitat, creating new wetlands, or even replacing jail cells. A real restorative justice commitment would make up for the damage done, as these examples show.

Lexington Kentucky: A community land trust funded from highway funds

For decades, Kentucky’s highway department had been planning a freeway expansion through Davis Bottom, an historically African-American neighborhood. The threat of freeway construction helped trigger the decline of the neighborhood. When the road was finally built a little more than a decade ago, the state highway agency committed to restoring the damage done to the area by investing in housing. As part of the Newtown Pike Extension project, the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet acquired 25 acres of land and provided funding to establish a community land trust for the construction of up to 100 homes.

In 2008, the Federal Highway Administration gave the project an award for this project, saying:

The Davistown project is the first CLT ever created with FHWA Highway Trust Funds. Eighty percent of the project, including the acquisition of CLT land and the redevelopment of the neighborhood, will be funded with these FHWA funds.

The FHWA Environmental Justice guide highlights the Lexington CLT as as a “best practice.”

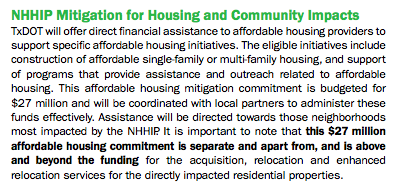

Houston, Texas: $27 million to build affordable housing to mitigate interstate freeway widening

Houston’s I-45 “North Houston Highway Improvement Project” would, like the I-5 Rose Quarter project, widen a freeway through an urban neighborhood. The Texas Department of Transportation, as part of the project’s environmental impact review process has dedicated $27 million to build or improve affordable housing in neighborhoods affected by the freeway.

Reno Nevada, State DOT providing land and money to cities and counties for affordable housing

Nevada DOT committed to using highway funds to pay for housing to mitigate effects of freeway expansion in Reno at the junction of I-80 and US 395.

NDOT will provide funds or land already owned by NDOT to others (Cities of Reno or Sparks, Washoe County) to build affordable replacement housing for non-Reno Housing Authority displacements. Those displaced by this project who wish to remain in the area will be given priority access to the replacement housing. After those needs have been addressed, the affordable housing will then be made available to those who qualify for affordable housing but were not displaced by the project. Residents will be considered eligible for this replacement affordable housing if they meet Section 8 eligibility requirements or Reno Housing Authority’s Admission and Continued Occupancy Policy (Reno Housing Authority 2018).

Federal Regulations encourage or require mitigating impacts.

The key environmental law governing federal highway projects is the National Environmental Policy Act. It requires that agencies identify the adverse environmental impacts of their decision, and then avoid, minimize or mitigate those impacts. In particular, NEPA mitigation includes “restoring the affected environment” and “compensating for the impact by . . . providing substitute resources or environments.” Using highway funds to replace housing demolished by a freeway is one key way in which the negative effects of a highway project on an urban community can be mitigated.

CFR § 1508.20 Mitigation.Mitigation includes:

(a) Avoiding the impact altogether by not taking a certain action or parts of an action.

(b) Minimizing impacts by limiting the degree or magnitude of the action and its implementation.

(c) Rectifying the impact by repairing, rehabilitating, or restoring the affected environment.

(d) Reducing or eliminating the impact over time by preservation and maintenance operations during the life of the action.

(e) Compensating for the impact by replacing or providing substitute resources or environments.

A federal executive order on Environmental Justice directs agencies to pay particular attention to the impacts, including the cumulative impacts of agency decisions on low and moderate income people and people of color. THe Federal Highway Administration’s Environmental Justice Policy specifically identifies impacts on neighborhoods as “adverse effects” of federal highway projects, and calls for both mitigating these impacts, and considering alternatives that minimize adverse impacts on communities.

- Adverse Effects. The totality of significant individual or cumulative human health or environmental effects, including interrelated social and economic effects, which may include, but are not limited to: bodily impairment, infirmity, illness or death; air, noise, and water pollution and soil contamination; destruction or disruption of human-made or natural resources; destruction or diminution of aesthetic values; destruction or disruption of community cohesion or a community’s economic vitality; destruction or disruption of the availability of public and private facilities and services; vibration; adverse employment effects; displacement of persons, businesses, farms, or nonprofit organizations; increased traffic congestion, isolation, exclusion or separation of minority or low-income individuals within a given community or from the broader community; and the denial of, reduction in, or significant delay in the receipt of, benefits of FHWA programs, policies, or activities.

FHWA Policy: It is FHWA’s stated policy to mitigate these disproportionate effects by providing “offsetting benefits” to communities and neighborhoods, and also to consider alternatives that avoid or mitigate adverse impacts.

What is FHWA’s policy concerning Environmental Justice? The FHWA will administer its governing statutes so as to identify and avoid discrimination and disproportionately high and adverse effects on minority populations and low-income populations by:

(2) proposing measures to avoid, minimize, and/or mitigate disproportionately high and adverse environmental or public health effects and interrelated social and economic effects, and providing offsetting benefits and opportunities to enhance communities, neighborhoods, and individuals affected by FHWA programs, policies, and activities, where permitted by law and consistent with EO 12898;

(3) considering alternatives to proposed programs, policies, and activities where such alternatives would result in avoiding and/or minimizing disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental impacts, where permitted by law and consistent with EO 12898

Taken together, the NEPA requirements for mitigation, and the FHWA’s policy on environmental justice require FHWA projects—like the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway Widening—to address the cumulative totality of the project’s effects on the neighborhood, including the disruption of community cohesion, the displacement of people and businesses and increased traffic congestion. The current project adds, as we have shown, to a long history of federally supported highway projects in the Albina neighborhood that have had devastating cumulative effects, including particularly, the destruction of hundreds of housing units, which are essential to the economic well being of the neighborhood and its residents, who, historically have been lower income and people of color. It is fully consistent with federal environmental policy and environmental justice requirements for ODOT to devote funds to rebuilding housing as a way to mitigate the damage it has done to the Albina neighborhood.