Portland’s $500 million Rose Quarter Freeway Widening Project is being sold as a way to reduce congestion: But it won’t work

In three recent commentaries at City Observatory, we’ve explored whether a wider freeway at Portland’s Rose Quarter would have any meaningful impact on daily traffic congestion. All of the available evidence says that even spending $500 million won’t make things noticeably better.

Widening the freeway won’t solve daily traffic congestion. More highway capacity generates more traffic–the phenomenon of induced demand is so well documented that it’s now called “The fundamental law of traffic congestion.” Added capacity encourages more people to drive, and in dense urban environments, there’s plenty of “latent demand” that almost immediately fills added lanes as soon as they’re built. Houston widened its Katy Freeway to 23 lanes, and it’s now even more congested and slower moving than before. Even PBOT and ODOT officials acknowledge that widening I-5 won’t reduce daily traffic congestion.

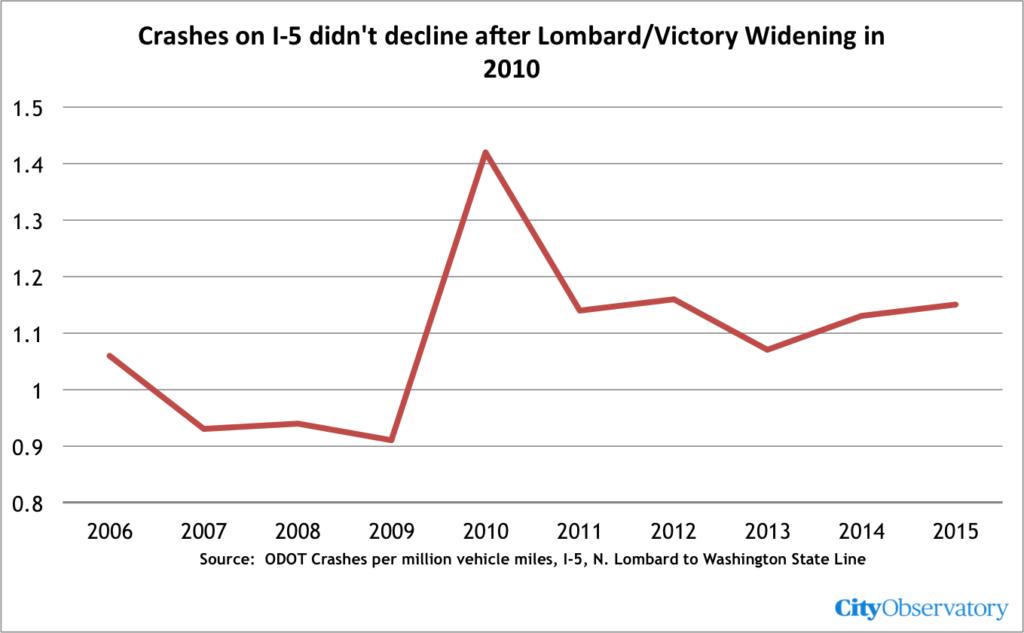

A wider freeway won’t reduce crashes that produce “non-recurring” congestion. Because they know they can’t reduce daily congestion, city and state engineers instead make a different claim: that more lanes and wider shoulders will reduce occasional congestion from crashes. But they don’t actually have evidence for that; instead the claim is just based on engineering “rules of thumb.” And our actual experience on this freeway, with the same drivers, has been just the opposite: After ODOT widened I-5 between Lombard and Victory Blvd. in 2010, crashes went up, not down. It’s not surprising: Metro’s State of Safety report shows that wider roads tend to have higher crash rates. If crashes don’t decline, ODOT can’t claim to reduce traffic congestion.

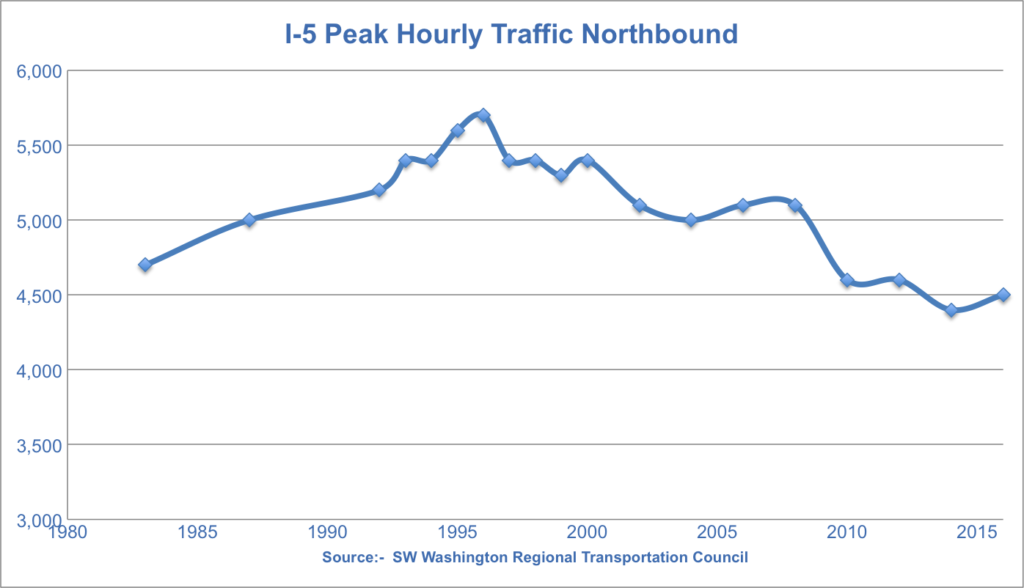

Wider roads will likely make congestion worse. There’s good evidence that funnelling more traffic onto the region’s roads will actually cause congestion to get worse. After ODOT widened I-5 north of Lombard, and expanded ramps onto the freeway, traffic congestion became worse, as more cars were funnelled even more rapidly into bottlenecks, causing the freeway to lose capacity. Consequently, the Interstate 5 bridge now carries about 10 percent fewer cars in the afternoon peak hour than it did ten years ago.