Yet again, a black citizen dies at the hands of the police. This event and the ensuing riots in Baltimore are a painful reminder of the deep divisions that cleave our cities. There’s little we can add to this debate, except perhaps to say that there’s a strong evidence for a point made by Richard Florida:

The real problem in Baltimore is race & class division – persistent concentrated poverty.

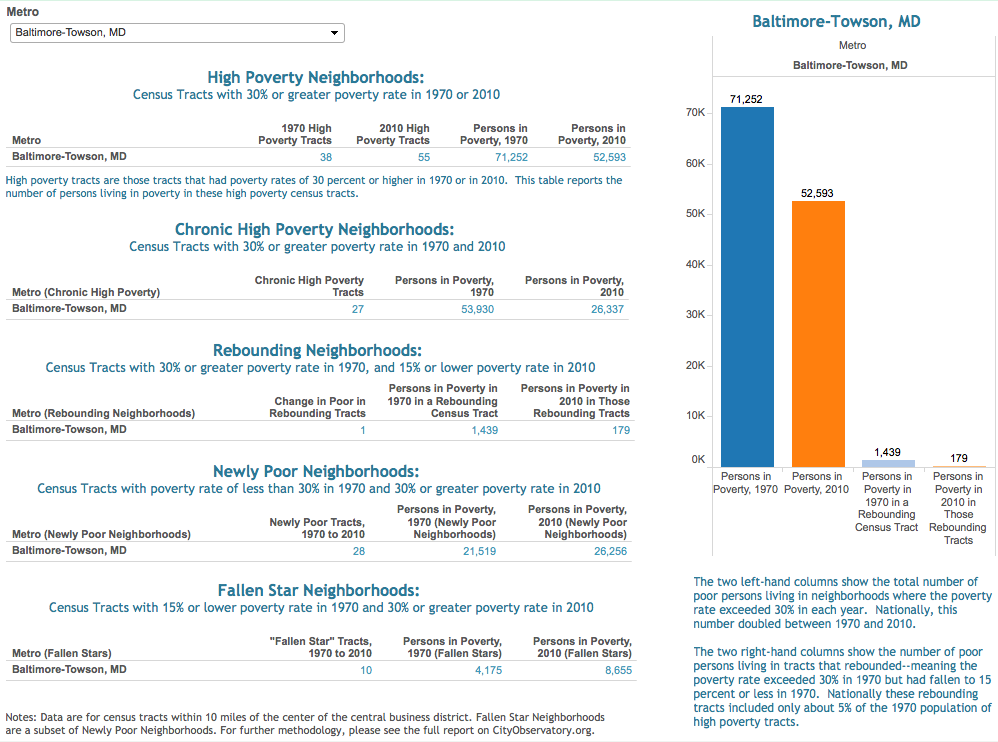

We’ve chronicled the persistence and spread of concentrated poverty in our recent reports and blog posts at City Observatory. Our Lost in Place report tracked the change in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty in the nation’s largest metro areas over the past four decades. Our dashboard for Baltimore shows that the number of high poverty neighborhoods in Baltimore increased from 38 in 1970 to 55 in 2010. And high poverty neighborhoods have hemorrhaged population. Only one census tract in Baltimore saw its poverty rate fall from above 30 percent in 1970 to less than 15 percent in 2010.

And as our map shows, the Baltimore has experienced persistent–and growing–concentrated poverty in many of its urban neighborhoods. Concentrated poverty remains rooted in the neighborhoods adjacent to the central business district–and has spread outward in the decades since 1970.

Earlier this month, we highlighted the connection between racial segregation and black white income disparities in the nation’s cities. Those places with the greatest levels of segregation regularly also had the biggest differences in incomes between black and white households. Segregation appears to be an important contributor to racial income disparities. These data show that Baltimore is somewhat more segregated than the typical large US metro, with a black-white dissimilarity index of 64, ranking about 20st highest (most segregated) of the largest metropolitan areas in the country. And on average black incomes in Baltimore were about 28 percent lower than white incomes, a slightly greater disparity than in the typical large metropolitan area. So while somewhat more severe than average, the levels of racial segregation and income differentials in Baltimore are hardly unusual in large metro areas.

Sadly, concentrated poverty is a problem which only becomes visible to many Americans when it erupts in the violence we’ve seen in the past few days in Baltimore. We hope the data provided here give everyone a sense of the depth and seriousness of the problem.