R.I.P. Road Pricing in Oregon: Dead before its even tried

More than just money, the demise of pricing monkey-wrenches state transportation policy

It’s no surprise: ODOT’s attempts to implement pricing have been half-hearted and still-born

Without pricing, Portland traffic congestion will grow worse, and this blows a hole in state and regional climate plans

This week, Oregon Governor Tina Kotek told the Oregon Department of Transportation to terminate the “Regional Mobility Pricing Program.” This pulled the plug on a legislatively mandated system to price Portland area freeways to manage traffic. The demolishes a key foundation for state transportation policy

- it costs the financially troubled and perennially mismanaged Oregon Department of Transportation billions that it was counting on to pay for major highway expansion projects

- it eliminates the cornerstone of the state’s strategy for reducing transportation greenhouse gases (which contrary to state plans, have been increasing).

- abandons the one tool that was likely to actually reduce congestion on Portland area roadways.

While this will ease the political unpopularity of tolling, it throws a monkey wrench into state transportation finances and policy.

ODOT’s approach to Road-Pricing: Half-hearted and still-born

No one who has following the Oregon Department of Transportation’s implementation of tolling and pricing should be the least bit surprised by the failure of this effort. The agency has had seven years to implement the 2017 law directing it to toll I-5 and I-205, and was still years away from actually doing anything. The demise of regional mobility pricing is just the latest in a series of half-hearted and still-born ODOT plans and policies for pricing Portland area roads. The elected regional government, Metro, has been claiming since before the millennium that it was interested in implementing road pricing to manage congestion. In 2009, the Oregon Legislature—as part of a compromise with environmentalists concerned about the added driving promoted by highway projects—enacted a state law directing ODOT to implement a road pricing demonstration project no later than September, 2012. ODOT drug its feet, and spent three years on desultory studies of pricing on two roads (Cornelius Pass and Highway 217) that went nowhere, and then claimed to have complied with the legislative mandate when, in 2011, the City of Portland set higher game-day rates for street-parking around Portland’s soccer stadium.

The truth is that while ODOT salivates at the prospect of getting and spending toll revenues, it really doesn’t have the slightest interest in using road pricing to efficiently manage the use of hugely expensive assets. Highway agencies are chiefly concerned about building more roads and bridges, not managing traffic. Congestion is a convenient and perennial excuse for demanding ever more money. And ODOT’s own consultant studies show that a system of road pricing would largely eliminate the need for additional capacity. It should be no surprise that an agency that has repeatedly dragged out and watered down pricing policies has yet another failure on its hands.

There’s another lesson here for environmentalists: As part of big transportation spending packages, highway builders have agreed to road pricing as a way to manage demand and reduce pollution, but have repeatedly reneged on that promise, and just kept spending on highway expansions. In 2009, the compromise between the pro-highway and environmental groups was that ODOT would implement a pilot road pricing program in three years. That didn’t happen. In 2017, environmentalists were assured that the Legislature had mandated road pricing on I-5 and I-205. That too, is now dead. In both cases, ODOT forged ahead with the highway spending programs these bills authorized, but delayed and ultimately abandoned implementing pricing. Time and again, highways get hundreds of millions in tax dollars, while environmental policies are delayed and forsaken.

Eliminating tolling makes a massive revenue problem even worse

Even before Governor Kotek’s latest decision, the finances of the Oregon Department of Transportation were in a shambles. The agency has systematically de-funded preservation and maintenance of roads to throw more money at these huge Portland area highway projects, even as their price-tags have doubled (I-5 Bridge Replacement), tripled (Abernethy Bridge), and quadrupled (I-5 Rose Quarter). Last June, the Oregon Transportation Commission produced a Kotek-ordered report to look at the finances of ODOT’s multi-billion dollar wish list of highway expansion projects. It found that even with tolling, ODOT would be billions of dollars short of what it needed. Its June 2023 “Financial Report” showed that without tolling the agency couldn’t come close to paying for these major projects.. Overall, the agency concedes that it is Portland area highway projects would cost $3.7 to $4.3 billion, and that the agency has only about $717 million for these projects—unless in is allowed to start levying tolls.

Both ODOT’s budget and Metro’s Regional Transportation Plan were both counting on billions of dollars in toll revenues to pay a significant part of these projects. Now, except for the Interstate Bridge Project, Kotek has taken toll revenues off the table.

Tolls are still OK—just on the I-5 Columbia River Bridge

The one exception to Kotek’s retreat on tolling is the Interstate Bridge Project a $7.5 billion bridge and freeway expansion connecting Portland and Vancouver. ODOT and WSDOT are counting on about $1.6 billion in toll revenues to pay a portion of project costs. Because most of the traffic on the I-5 bridges is Washington residents coming to Oregon to work or avoid Washington sales taxes, between three-fifths and two-thirds of tolls will be paid, not be Oregon voters, but by Washington residents. The chief immediate effect of Governor Kotek’s decision will likely to be shifting the responsibility for running the toll collections system to Washington State, which already has a “Good-to-go” toll tag system, complete with back office and billing functions.

But killing off the Regional Mobility Pricing Program has a major consequence for the traffic and environmental impacts of the IBR project. The IBR would impose tolls of $2.80 rising to $4.34 on the I-5 bridge. The IBR’s own traffic consultants have said that this will produce a major diversion of traffic from I-5 to I-205 (which won’t be tolled). The pat response of IBR officials to this problem was to claim that Oregon’s Regional Mobility Pricing System would impose tolls on I-205 which would discourage diversion (something, incidentally, that they never documented as part of their environmental work). But with RMPP dead, there will be no tolls on I-205. Washington State’s Legislature already adopted a ban on tolling its portion of I-205 as part of the legislation it adopted legislation to channel funding to the IBR project. Washington law provides:

(2) The Interstate 5 bridge replacement project is designated an eligible toll facility. Tolls are authorized to be imposed on the Interstate 5 bridge replacement project. Tolls may be charged for travel only on the existing and replacement Interstate 5 Columbia river bridges. Tolls may not be charged for travel on the Washington state portion of Interstate 205.

Revised Code of Washington 47.56.902 (Emphasis added).

IBR’s own studies show that tolling just I-5, and not the parallel I-205 bridge will depress traffic on I-5 and cause diversion to I-205. The following chart shows the predicted daily level of trips across the I-5 bridge according to the IBR’s published environmental analysis. Currently about 140,000 vehicles per day cross the I-5 Columbia River Bridges The red line on the chart shows what IBR contractor Stantec says will happen in its more detailed “Level 2” traffic study when tolls are implemented in 2026. Traffic will fall by almost half, to only about 70,000 vehicles per day. The modeling says that most of those vehicles per day will divert to I-205.

Shifting 30,000 cars a day to the I-205 bridge will have its own traffic impacts, and is particularly important because I-205 is the principal access route to Portland International Airport. Personal and freight trips to the airport are among the most valuable and time sensitive trips in the region, and tolling IBR, and not tolling I-205, will make airport access much worse. Failing to disclose this kind of impact would be a fatal flaw in the IBR’s Environmental Impact Statement.

Shifting 30,000 cars a day to the I-205 bridge will have its own traffic impacts, and is particularly important because I-205 is the principal access route to Portland International Airport. Personal and freight trips to the airport are among the most valuable and time sensitive trips in the region, and tolling IBR, and not tolling I-205, will make airport access much worse. Failing to disclose this kind of impact would be a fatal flaw in the IBR’s Environmental Impact Statement.

Without de-congestion pricing there will be more congestion

The most profound irony of Kotek’s decision is that it is coming just as North America is about to witness the most powerful demonstration of the advantages of de-congestion pricing when New York City implements its pricing system for cars entering lower Manhattan. While opponents characterize tolling as just an additional tax, the experience of major cities around the world is that pricing provides “value for money”—that the travelers who end up paying the tolls get a faster, smoother, more predictable trip. Indeed, road pricing is the only strategy that’s been shown to effectively reduce traffic congestion.

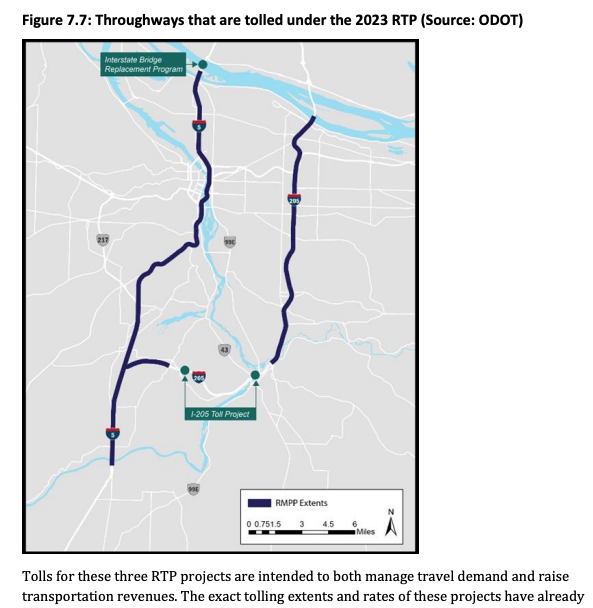

Metro’s just-adopted 2023 Regional Transportation Plan counts heavily on a system of variable pricing on all of the region’s “throughways” including I-5, I-205, and other highways, such as US 26, Highway 217, and I-84, to manage peak hour demand.

Metro’s RTP said that road pricing was essential to reducing traffic congestion:

• Tolling is expected to reduce total VMT.• Tolling is expected to reduce congestion on I-5 and I-205.• Tolling will likely lead to an increase in carpooling. .• Tolling will likely encourage people to shift when they travel.Metro Regional Transportation Plan, page 7-30

Without road pricing, Metro won’t achieve either congestion reduction goals called for in its Regional Transportation Plan. What the Governor’s abandonment of pricing means is that Oregon will continue suffer worse and worse traffic congestion, because it gives travelers no incentives or feedback (through variable tolling) to encourage them to travel at different times, or take different routes or destinations. Unpriced roadways will lead to overuse, and just having tolls on one road segment or bridge (like the I-5 bridge) will make traffic congestion worse elsewhere.

More traffic means more greenhouse gas emissions

For fifteen years, Oregon has had an ambitious goal of reducing greenhouse gases by 75 percent from 1990 levels by 2050. It’s made notable progress in cleaning up electricity generation, making manufacturing more efficient, and lowering emissions from homes, stores and offices. Where it has utterly failed to make progress is in transportation, where greenhouse gas emissions are now about 20 percent higher than they were in 1990. While the state has mandated cleaner fuels, and cars have gradually become cleaner, the state and regional climate strategies also call for measures to reduce the amount of driving. These strategies (ODOT’s State Transportation Strategy and Metro’s Regional Transportation Plan) both count heavily on road pricing to reduce VMT.

Metro’s RTP claims it will comply with a state requirement to achieve a 35 percent reduction in per capita vehicle miles traveled, largely due to road pricing:

Pricing Policy 5. Reduce greenhouse gas emissions and vehicle miles travelled per capita while increasing access to low-carbon travel options. The Metro Regional Congestion Pricing Study found that pricing has the potential to help the great Portland region reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve Metro’s climate goals. All of the scenarios tested in the study showed reductions in greenhouse gas emissions through reducing overall VMT per capita. Pricing policies were found to be effective in encouraging drivers to change their travel behavior such as using more sustainable travel modes like transit, walking, or biking. These changes in behavior are key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the region.page 3-52

Nixing road pricing means that Metro won’t reduce vehicle miles traveled as planned, and that greenhouse gas emissions will be considerably higher than called for in the plan, putting Metro in violation of state greenhouse gas reduction regulations.

Lots of Homework

Cancelling road pricing was the easy part. Now state and local authorities will have to pick up the pieces, re-writing major pieces of state and local transportation plans. All these plans assumed we’d have road pricing to provide funding, manage demand and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The plans that hinged on those assumptions are now effectively a dead letter. Here are just some of the obvious items that must be fixed:

- ODOT will have to come up with billions of dollars to finish its I-205 Abernethy Bridge project, and $1.9 billion Rose Quarter project.

- ODOT and LCDC will have to re-do their climate plans, which claimed that road pricing was one of the ways the state would reduce driving to achieve greenhouse gas reduction goals.

- Metro will have to amend its regional transportation plan, which not only counted on tolling to pay for projects, but also assumed congestion pricing would be used to manage area throughways, reducing congestion, and lowering pollution. Likewise, Metro’s climate plan assumed the state would implement a sweeping system of congestion pricing on Portland throughways, to lower VMT and achieve climate goals. All those assumptions are not flatly wrong.

- Finally, the Interstate Bridge Project will need to revise its Environmental Impact Statement to disclose that tolling the I-5 bridges and not tolling I-205 will produce massive diversion of traffic to I-205, will likely slow traffic to and around Portland International Airport, and will mean that the massive $7.5 billion freeway widening project will be perpetually under-utilized–carrying less traffic that the existing I-5 bridges for the foreseeable future.