Highway department’s are selling multi-billion dollar highway widening projects based on flawed traffic projections.

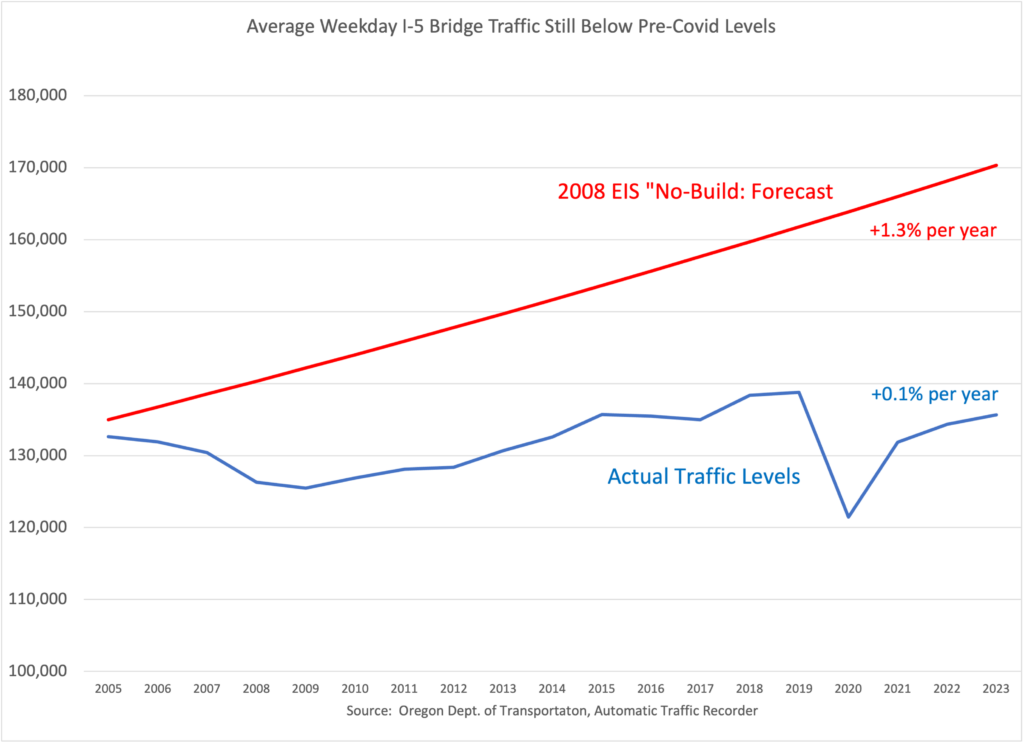

The projections prepared for the predecessor of the proposed $7.5 billion Interstate Bridge Replacement project predicted traffic would grow 1.3 percent per year after 2005. In reality, traffic across the I-5 bridges has increased by only about 0.1 percent per year since then (and at its pre-Covid peak, had increased only 0.3 percent per year).

Actual I-5 traffic levels are more than 30,000 vehicles per day below the levels forecast for 2024 in the Columbia River Crossing EIS. Rather than increasing by 30,000 vehicles, I-5 weekday traffic has only increased by 3,000 vehicles in 18 years.

Inaccurate and biased traffic models are a misleading and even fraudulent basis for multi-billion dollar spending decisions.

Claims that we need widen I-5 between Portland and Vancouver are based on projections from traffic models. The best evidence of how well a traffic model works is how accurate its predictions have been. By that standard, we already know that the traffic models developed for the Interstate Bridge Project are simply wrong and untrustworthy.

We know because we’ve run that experiment. In 2008, the Oregon and Washington highway departments released an Environmental Impact Statement for the same project—then called the Columbia River Crossing—claiming that if nothing was done—the so-called “No-Build” scenario—traffic on the I-5 bridges between Portland and Vancouver would grow at an annual rate of 1.3 percent per year for the next twenty five years.

Now, more a decade and a half later, we have the actual lived experience to see how accurate this forecast was. The following chart shows the CRC “No-Build” forecast (in red) and actual weekday traffic levels (in blue) as reported by ODOT’s traffic-counting website. It’s obvious that the traffic modeling for the CRC was wildly exaggerated. The model claimed that traffic was going to grow by now to about 170,000 vehicles per weekday—an increase of 35,000 from 2005 levels. In reality, weekday traffic on the I-5 bridges is now just 136,000. Instead of growing at a predicted 1.3 percent per year, traffic growth averaged just 0.1 percent per year from 2005 to 2023.

We’re now 18 years—almost three-quarters of the way—through the 25-year period covered by the earlier traffic projections. A failure this large is strong evidence that no one should trust the highway department’s modeling of future traffic levels: Their own history shows they’re guilty of error and exaggeration, problems that they have neither admitted nor fixed.

What this demonstrates is that these highway department models aren’t accurate, and that they are biased. They don’t accurately predict growth rates, but the errors aren’t random—the models consistently exaggerate future growth, which neatly fits the agenda of the highway departments who are trying to sell the public on the “need” for these projects. Arguably, these intentionally exaggerated over-estimates constitute a fraud against the federal government, which is being asked to fund a much larger than justified project, based on demonstrably false claims about future traffic growth.

Indeed, there was a temporary dip in travel during the pandemic. But the models were wildly wrong even before Covid. Between 2005 and 2019 (the last pre-Covid year), traffic grew at a paltry 0.3 percent annual rate—less than one-fourth as fast as predicted by the highway department models. We’ve had roughly three years to recover from the lock-downs and reduced travel of the pandemic, and travel levels still have not rebounded to pre-Covid levels. That suggests that these models, which simplistically assume ever-upward growth in travel are simply wrong.

One other note: sharp-eyed readers will see that the CRC traffic estimate for 2005 (135,000) is higher than ODOT traffic counts for that same year (132,600). The reason is CRC “rounded up” the figure—traffic actually never reached 135,000 until 2015. ODOT traffic count data report that weekday traffic was 132,600 in 2005 and 135,600 in 2023, in increase of 3000 vehicles over 18 years. Over a period where models claimed traffic would increase by 30,000 vehicles, they increased by barely a tenth as much: 3,000 vehicles.