Why does it take four years and $200 million to serve up a warmed-over version of the Columbia River Crossing?

The Interstate Bridge Replacement Project’s director admitted that he’s just pushing “basically the same” project that failed a decade ago, but in the process, he’s spent $192 million on consultants, with the largest single chunk of that money ($75 million) going to his former employer, WSP.

And WSP has returned the favor, providing Johnson with questionable reports that purport to rule out examining an immersed tunnel option which exaggerate project benefits to qualify for federal funding.

Between the failed CRC (which cost nearly $200 million a decade ago) and its rebranded clone, the IBR, the two states will have spent nearly $400 million, mostly on consultants, and without turning a shovel.

Nearly 10 percent of all of IBR’s consulting largesse—more than $20 million—has gone to public relations firms to help it sell the project

Greg Johnson is the director of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project (IBR), a joint effort of the Oregon and Washington State departments of transportation to spend something on the order of $9 billion on a giant freeway project to replace the existing I-5 bridges over the Columbia River connecting Portland and Vancouver.

The IBR is simply a re-branded version of the failed “Columbia River Crossing”—a nearly identical proposal that foundered in 2014, after a decade of planning and scheming and about $200 million spent, mostly on consultants to develop the proposal. In 2019, Governors Jay Inslee and Kate Brown announced a renewed effort to move the project forward under its new name “Interstate Bridge Replacement.”

Since then the Oregon and Washington highway departments have spent the past four years moving the project forward, along the way repeating many of the mistakes of their predecessors. A key issue, whether the bridge’s proposed 116-foot navigation clearance will satisfy the US Coast Guard is still unsettled, as are key environmental questions. And meanwhile, the project’s budget has ballooned from $4.8 billion to as much as $7.5 billion, and now promises to increase further, to as much as $9 billion.

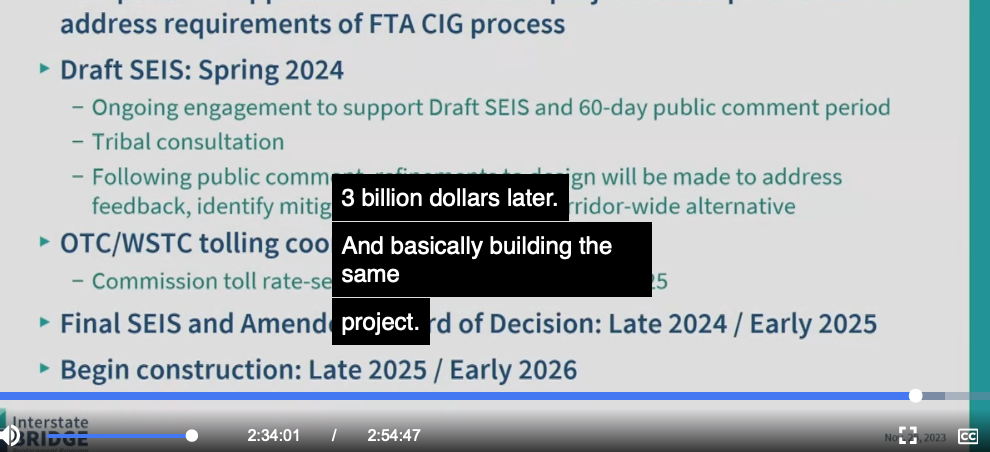

“Basically building the same project”

At a meeting of the Joint Oregon and Washington legislative committees overseeing the project on November 27, Johnson, pushing back against claims that people needed more time to study and review the project, dropped his guard and conceded that the IBR is simply a very slightly warmed over version of the old CRC. He told legislators: the pricetag was higher now, and that they were just repeating the Columbia River Crossing:

“Here we are $3 billion later, and basically building the same project.”

If it is basically the same project—and indeed, it really is—that raises a critical question: Why has it taken more than three years nearly $200 million in consultants to get here?

$200 million more for consultants to design “basically the same project”

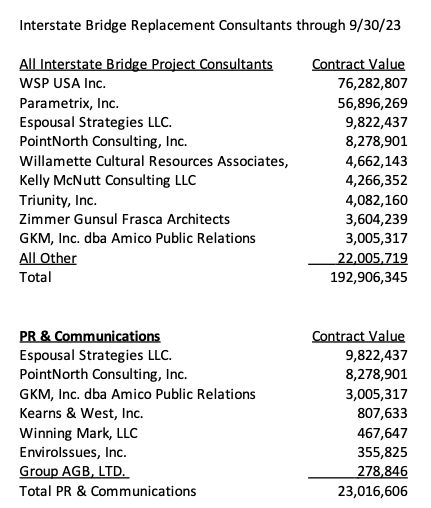

Neither the IBR’s website nor its lengthy presentations to the Legislature and other public bodies discloses how much the program has spent to date. So we filed a public records request to obtain this information. Through the end of the third quarter of 2023, the Interstate Bridge Project had contracted for nearly $193 million in consulting services. This amount doesn’t include the cost of WSDOT and ODOT staff time, which undoubtedly pushes the total cost for planning so far well over $200 million.

The nearly $200 million obligated for the latest round of consultants for this project comes on top of another nearly $200 million spent between 2004 and 2014 on its failed predecessor, the Columbia River Crossing. The Oregonian reported:

. . . the Columbia River Crossing was highly lucrative while it lasted for a handful of big engineering and consulting firms. The CRC paid $199.4 million to 171 companies, consultants and others in the last 10 years, according to the latest numbers released to The Oregonian by the Oregon Department of Transportation.

Jeff Manning, “Columbia River Crossing: Tab approaches $200 million after I-5 bridge project shuttered,” The Oregonian, April 19, 2014.

The Oregonian published a long list of the CRC consultants. Many of these same firms (or their legal predecessors) cashed in on that work as well, and are being asked to repeat the same scope of work, for as Johnson puts it “basically building the same project.”

The largest single beneficiary of this consultant spending spree is a firm called “WSP” which is one of the largest planning and engineering consulting firms in the world. It has bought up a number of other consulting firms, including the former Parsons Brinckerhoff—a consultant for the Columbia River Crossing. WSP has gotten more than a third of all of the consulting business for the IBR: $76 million in contracts out of the $192 million total.

And the person responsible for hiring and supervising the IBR contracts with WSP is Greg Johnson, the IBR project’s director, who as it turns out is a former Vice President of WSP, as disclosed in his biography:

Most recently, he [Johnson] served as a Senior Vice President at WSP USA, one of the nation’s largest engineering firms, as the National Director for Construction Management & Services . . .

So, in Johnson’s words, he has hired his former employer to design “basically the same project” as the old Columbia River Crossing. And, for the record, under Johnson’s leadership, WSP has gotten a much bigger slice of the IBR consulting pie than it ever did on the Columbia River Crossing project. From 2004 to 2014, Parsons Brinckerhoff (the WSP predecessor) got just $23 million in contracts to work on the Columbia River Crossing. Over the past four years, WSP (which now includes the former Parsons Brinckerhoff firm) has gotten more than three times as much of this consulting business—$76 million—to design “basically the same project.”

Quid pro quo, WSP?

In return, WSP has delivered up to Johnson just the technical work Johnson needs to bury alternatives he doesn’t want to pursue. WSP, for example, produced an error-riddled report saying that an immersed tube tunnel wasn’t a viable alternative. Engineer Bob Ortblad pointed out that the WSP report, issued in July 2021, lacked a legally required engineer’s stamp, which wasn’t added to the report until April, 2023—long after the agency had ruled out the immersed tunnel alternative. As Ortblad later found—and IBR ultimately conceded—the WSP tunnel report contained a major calculation error. The WSP report on the immersed tube tunnel overstated by a factor of two how much material would have to be dredged for the deep bore tunnel. Even though IBR has admitted the error, it is not revisiting its earlier decision to rule out the tunnel option.

In addition, WSP provided a questionable report critical to obtaining federal funds. WSP was paid by the IBR to prepare a “benefit-cost” analysis of the project, a requirement for qualifying for federal funds. The benefit-cost analysis is replete with errors and questionable assumptions that consistently over-state potential benefits and understate actual costs. In addition, neither IBR nor WSP revealed that WSP had a significant material conflict of interest in preparing the benefit-cost report: If the WSP report didn’t generate a favorable benefit-cost ratio, the IBR project would be ineligible for federal funds and WSP would lose out on its $75 million in contracts. The recent announcement that the project’s costs are going to go up yet again, just days after getting notice of $600 million in promised federal funding, casts further doubt on this exaggerated benefit cost analysis. At a likely pricetag of $9 billion, the project’s meager (and overstated) benefits likely no longer qualify it for federal funding.

After being challenged to respond on this issue in December 10, 2023 legislative hearing, Greg Johnson replied.

Our team does not have a conflict of interest. This is how projects of this type are done across the nation. The DOTs don’t have all of the personnel to do projects of this size so there are consultants who are brought on. There are not conflicts of interest as has been indicated.

The issue, of course, is not whether ODOT and WSDOT use consultants, but whether they use a consultant with an obvious and blatant conflict of interest. Johnson claimed there was no conflict of interest but failed to acknowledge or refute the fact that WSP holds over $75 million in contracts on the IBR, and that those contracts would be in jeopardy if it turned in an unfavorable benefit-cost analysis. Johnson also did not explain why this task was assigned to WSP, rather than an independent, objective consultant with no stake in the outcome of the report. And if, as Johnson describes them, his former employer WSP is serving as a member of “our team,” then it’s very clear that the assumptions that power WSP’s overstated benefits are shaped by “team” thinking, and not any independent professional judgement.

When Johnson says “this is how projects of this type are done across the nation,” perhaps he means its commonplace to throw tens of millions of dollars of work to a former employer, and then repeatedly ask them for technical reports that provide a pretext to ignore alternatives you don’t like, and make questionable assumptions that help you to qualify for federal funding.

A bonanza for spin merchants

While Johnson’s former employer, WSP has gotten the lion’s share of the IBR consulting largesse, another huge chunk of money has gone to a stable of spin merchants to help sell the IBR project. More than $20 million of the nearly $200 million in consultant cash has gone to seven public relations and communication firms, as shown above.

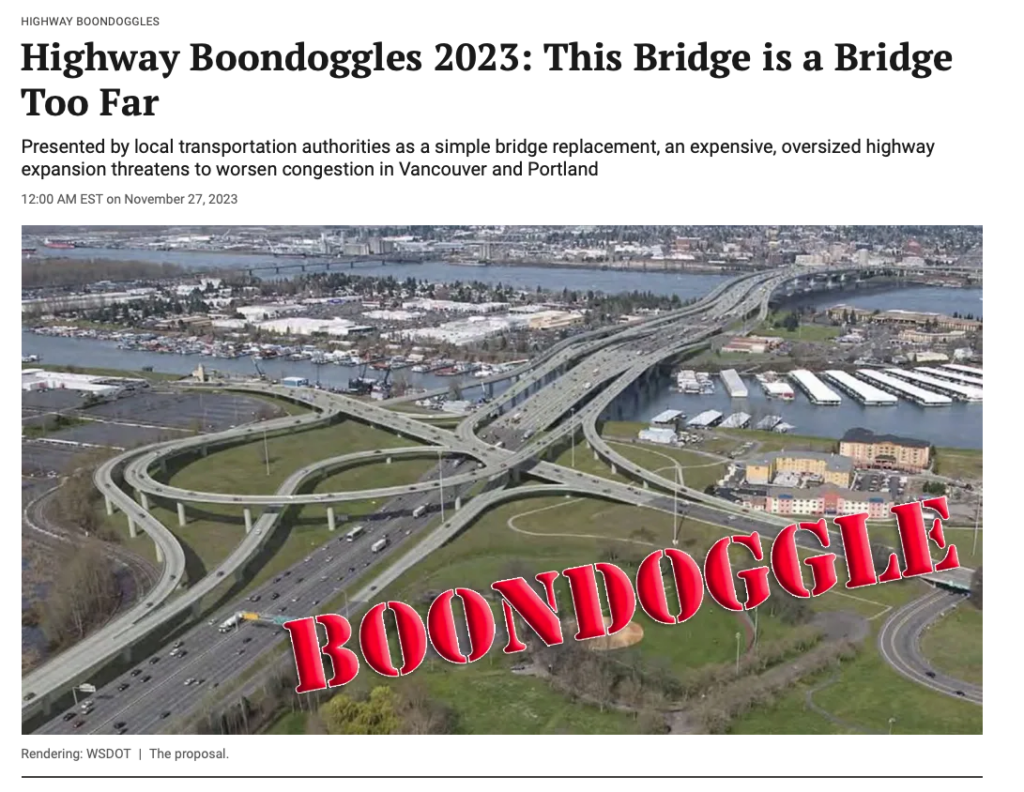

Even though they routinely flog any favorable press coverage of the IBR project, the IBR team hasn’t made any mention of its latest national headlines. The independent US Public Interest Research Group named the IBR to its list of national highway boondoggles—in fact, the IBR is the single most expensive boondoggle on this year’s list.

Editor’s Note: Post updated to correct formatting and typographical errors.