Advocates for a $5 billion transportation bond that Portland area voters will be deciding in November are making a specious argument about it being an equity measure.

Its largest single project, a multi-billion dollar light rail line serves the some of the region’s whitest and wealthiest neighborhoods and has as its destination a suburban lifestyle mall.

The bulk of the money in the measure supports projects in highway corridors, including a subsidy to cars driving to the Portland airport.

Because the measure does nothing according to the advocate’s own estimates to reduce greenhouse gases, it’s inequitable to the frontline communities that bear the burden of climate change.

Some of the proponents of a $5 billion tax measure being presented to Portland’s voters on November 3 are claiming that it’s a way to right historic wrongs to the poor and people of color. CityLab published one such commentary last week, with a headline asserting that the measure will help communities of color; it features a picture of one of Portland’s right rail lines.

But if you look closely at the measure, it’s really just transportation pork barrel politics, like the days of old, and the biggest shares of the money go to projects that disproportionately benefit whiter communities and higher income households. Despite a relative handful of measures—like free and reduced price transit for school aged kids—that make sense on their own, it’s a package that consists mostly of road projects that could and should be paid for by road users through the gas tax. Instead, car users get the equivalent of a 30 cent a gallon subsidy for driving. What’s worse, is that the measure cannibalizes the payroll tax—which the region has used for 50 years to subsidize transit operations—to fund capital expenditures, at a time when the local transit system is facing desperate financial conditions.

But let’s focus on the biggest single project in the Metro package: roughly a billion dollars toward the local share of the costs of a $3 billion expansion of the region’s light rail system. On paper, that seems good, but as long-time Tri-Met planner GB Arrington pointed out, this particular light rail project makes no sense as a transit or urban development measure.

The claim in the CityLab article is that the measure “invests in Black and Brown communities.” But when it comes to the single biggest project in the package, the proposed Southwest Light Rail benefits the whitest, wealthiest part of the region. The same is true of other major components of the package, which chiefly invest in highway corridors, not neighborhoods. Here are the facts.

SW light rail would disproportionately serve Portland’s whitest neighborhoods

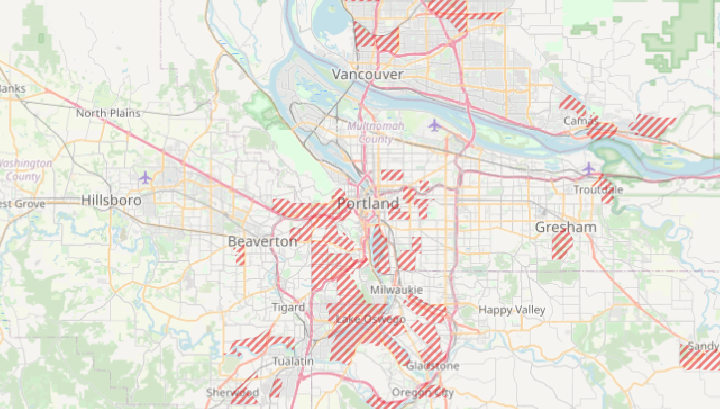

At City Observatory, we’ve extensively studied the racial and ethnic diversity of the nation’s largest metro areas, including Portland. While Portland has fewer Black residents than most large metros, it has proportionately more Hispanic and Asian residents, and it is overall, one of the least racially and ethnically segregated metro areas in the nation. But like every large US metro area, it has a share of neighborhoods that are not diverse, and that are disproportionately composed of white, non-Hispanic residents.

As part of our study, America’s Most Diverse, Mixed Income Neighborhoods, we identified all of the non-diverse predominantly white neighborhoods in the nation’s 50 largest metro areas. We computed racial diversity using the Racial and Ethnic Diversity Index (REDI), and flagged those tracts that were among the 20 percent least diverse of all tracts in large metro areas nationally, and in which the majority racial/ethnic group was white, non-Hispanic. Here’s a map of the Portland area’s non-diverse, white neighborhoods.

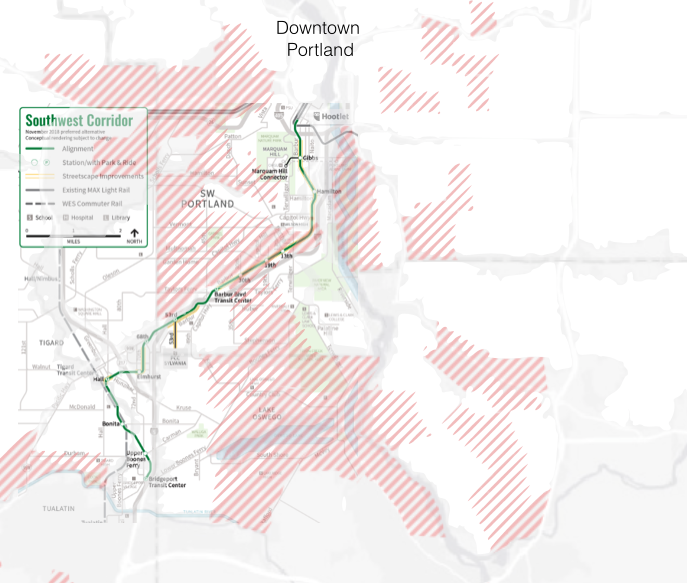

The area with the largest concentration of these non-diverse white neighborhoods is the the southwest quadrant of the city of Portland, an area running from the city’s West Hills to the city of Lake Oswego. The route of the proposed Southwest Corridor light rail line bisects this large concentration of non-diverse neighborhoods. Here’s a close-up of the same data, with the route of the light rail line super-imposed on these low-diversity white neighborhoods.

Light Rail to Portland’s high income suburbs

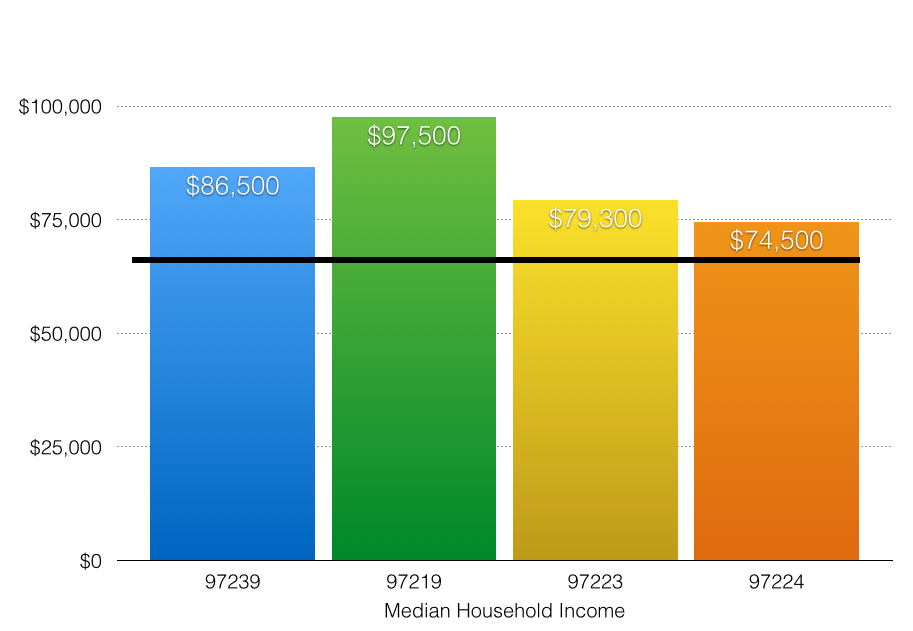

Not surprisingly, these predominantly white neighborhoods are also among the wealthiest in the region. The neighborhoods of southwest Portland and the suburbs in this part of the region are hardly distressed communities. Don’t take our word for it: Let’s look at the Distressed Communities Index just released by the Economic Innovation Group. It ranks all the zip codes on the US on a 100 point scale of economic distress, based on a combination of income, poverty, and employment indicators. The proposed SW Light Rail project runs through four zip codes outside of downtown Portland: 97239, 97219, 97223 and 97224. Three of these four are rated “prosperous”–the highest income of five categories in the EIG ranking, and one is rated “comfortable.” None are mid-tier, at-risk, or distressed.

The average incomes of these neighborhoods are higher than for Multnomah County, the region’s most central, urban county. Median household incomes in zip code 97219 are among the highest in the region, at just slightly less than $100,000. The following chart shows the county-wide median and the median incomes in the four zip codes directly served by the proposed light rail line.

Destination: Suburban shopping mall

The southern terminus of the proposed Southwest Light Rail line is a “lifestyle center” shopping mall called Bridgeport Village.

Bridgeport Village is home to a host of national chain stores catering to high-end households. The mall’s owners describe it as:

. . . an outstanding and enviable array of exclusive, internationally renowned stores and boutiques which include The Container Store, Anthropologie, GAP, Lululemon, Apple, Crate & Barrel, Brandy Melville, Madewell, Sephora, Sundance, Eileen Fisher, MAC Cosmetics, Tommy Bahama, Soft Surroundings and the largest Regal IMAX Theatre in the state.

They too, note the area’s high income demographics. The mall’s primary trade area has an average household income of $89,000 compared to $74,000 in the rest of the metropolitan area.

Other projects also chiefly benefit white, wealthy populations

Another project subsidized by the bond measure is a massive freeway interchange serving Portland International Airport. The interchange will make it quicker and easier for people to drive to the airport (and not incidentally, undercut the relative attractiveness of the already existing light rail service that goes direct to the airport terminal). And the users of facilities like the airport have higher incomes that the rest of the region’s population. According to Statista, person with an income of $80,000 a year is about 6 times more likely to be a frequent air traveler than someone with an income under $40,000 per year. Ironically, because the Port of Portland charges market rates for parking ($3 an hour; $24/day) it’s the one place where car users actually shoulder something approaching the cost of their trips, and the Port could easily fund this road improvement out of the fees it charges users; but it prefers to ask that the general public subsidize car trips to and from the airport.

The project proponents claim that the proposal will support investments in safety and pedestrian improvements in the region. But the bulk of these monies are focused on highway corridors. As we’ve discussed at City Observatory, as a practical matter, “pedestrian safety” improvements in and along highways are of dubious value in creating more walkability, and are in many cases, actually highway improvements—designed to facilitate more and faster car travel.

What this tells us about equity

Urban leaders around the nation are grappling daily with the question of how to fashion policies that achieve “equity.” There’s a cacophony of voices calling for greater equity, but no definitive yardsticks to say what this means, or measure whether we’re making progress, or even moving in the right direction. If a light rail line through the richest, whitest portion of a region contributes to “equity” than arguably pretty much any investment could. Likewise projects that expand capacity on suburban highways, or make it easier to drive to the airport, rather than take the light rail system we’ve already built.

There are pieces of the Portland measure that do support equity, like free and reduced price transit fares. But the most expensive items in the package hardly serve disadvantaged front-line communities. Beyond that, we know that low income communities and people of color are those most likely to bear the brunt of the effects of climate change, which means that the Metro bond measure’s abject failure to reduce the region’s transportation greenhouse gases is, itself, highly inequitable.

The point is that without a clear definition of what constitutes “equity,” this criterion is meaningless. Given our current approach to the subject, “equity” is as vague, personal, and subjective as “beauty.”

Our discussions of equity need to be far more specific and quantifiable: Who benefits, and how much? And how do we address the underlying inequities that are built into the existing institutional arrangements for transportation, and that are never questioned: like virtually universal free parking, or policies that prioritize the faster movement of cars over the safety and livability of urban neighborhoods? Is there anything more equitable than adequate funding for bus operations to assure greater frequency? We should make equity a key criteria for guiding our transportation policies, but we should do so in a way that systematically makes our overall society more equitable, rather than being a subjective talking point for a particular pet project.

It’s worth imagining what a real, equity-driven regional agenda would look like. For starters, it wouldn’t be based on the premise that everything has to be viewed through the lens of transportation. While inequity manifests itself in the transportation system, the problem is much broader and more fundamental, and is rooted in land use and housing policies, like the prevalence of single family zoning in the Southwest corridor that this proposal does nothing about. An equity focused agenda might also try to learn from and adapt based on the lessons of the Covid pandemic. Arguably right now, widespread and free or inexpensive access to high-speed Internet is a more salient equity issue. Framing this single largest investment in the region’s history solely as a transportation issue forces all communities to play a transportation game rather consider more broadly the range of investments that would provide the livability and opportunity communities are asking for. Finally, a real equity measure should pay as much attention to how monies are raised as it does to how they’re spent, and be funded by assessing the costs to users. People are adaptable, transportation systems much less so. Investing in steel and concrete before investing in new patterns of cost allocation and usage is today short-sighted and should be unthinkable.