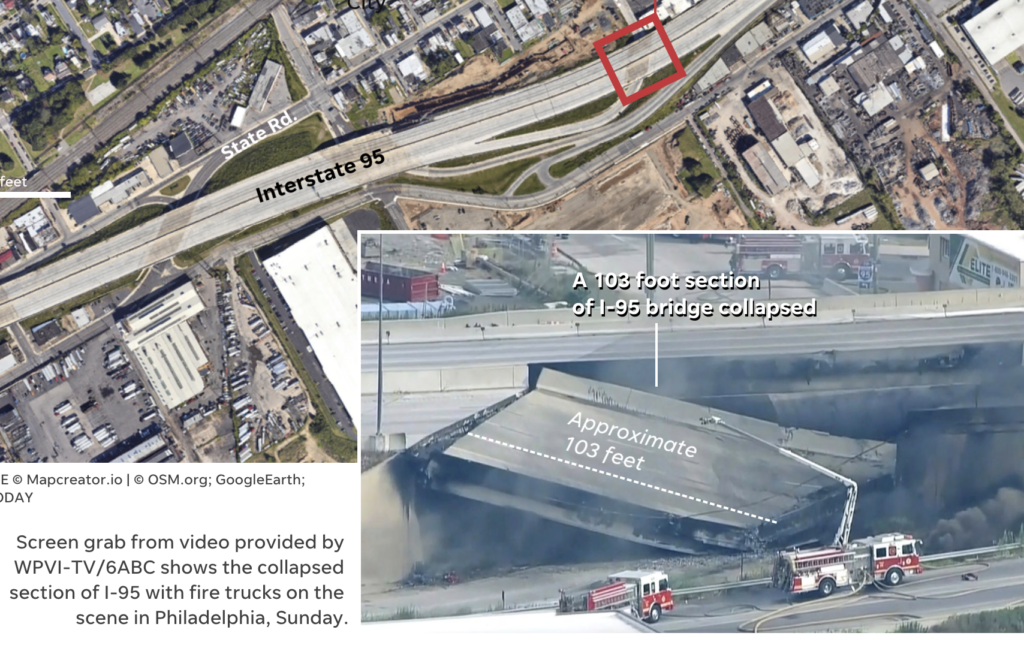

On Sunday June 11, a tanker truck caught fire on I-95 and the intense heat caused a section of the freeway to collapse. I-95 is one of the nation’s principal north-south connections, and carries 160,000 vehicles per day. It’s expected that repairs to the roadway could take months.

What would commuters and travelers do without this vital chunk of roadway? Surely, we’re headed for gridlock and carmageddon!

But on Monday morning, despite some localized delays, pretty much nothing out of the ordinary happened. Local TV station NBC10’s chyron shouted “COMMUTER CHAOS,” but their reporter actually found that traffic was mostly, moving steadily:

With the start of the workweek, following the collapse and closure of one of the city’s busiest thoroughfares, commuters on Monday seemed to handle the issue caused by the fiery collapse of a section of Interstate 95 fairly well.

Even as the about 160,000 vehicles that are estimated to drive along I-95 on any given weekday have had to find an alternate route due to the roadway’s collapse, traffic was moving relatively steadily.

While there were reports of slowdowns citywide, at the start of rush hour at about 7 a.m., the longest delay at the time was about 29 minutes for those headed eastbound along I-476 toward I-676.

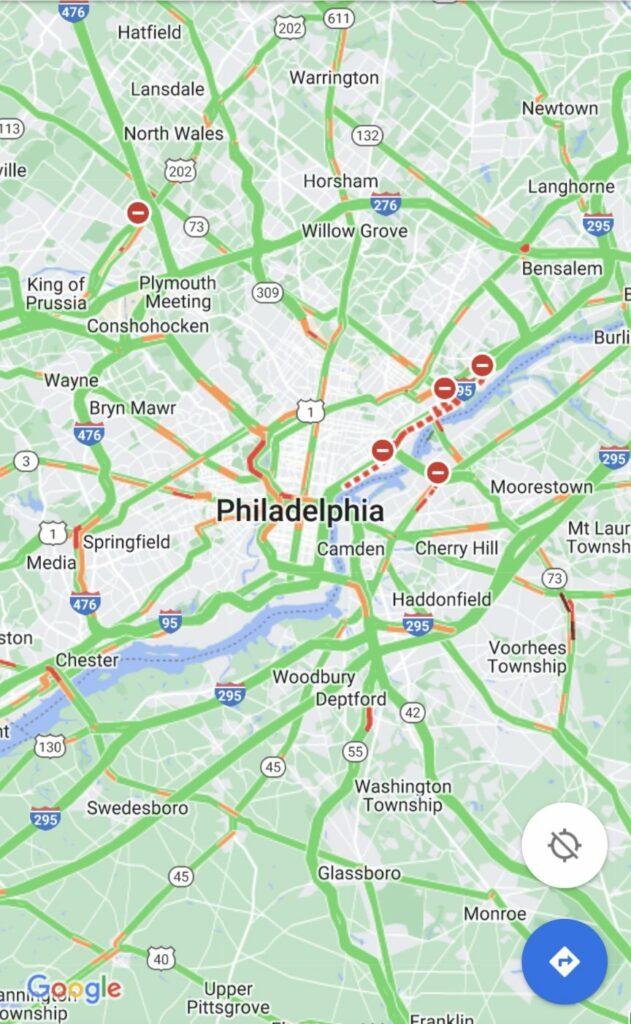

Here’s what Monday morning traffic looked like according to Google Maps (h/t to tweet from Daniel Trubman)

and for comparison, here’s what a typical Monday morning looks like, according to Google’s historical data. If anything, overall traffic seems to be moving with more alacrity that on a typical Monday, despite a portion of I-95 being closed.

This isn’t an unusual occurrence. The same scenario is repeated, time and again, whenever a major section of roadway is removed from service, whether by construction, repair, or as a result of crashes. Just ask Los Angeles, or Seattle, or Atlanta, or Minneapolis, or Portland. In every one of these cities, a key roadway was taken out of service for days, weeks or months. In every one of these cities, highway departments predicted calamitous delays and gridlock. And in every one of these cities, pretty much nothing happened. Traffic “just disappeared” and driving conditions “weren’t so horrible” and in several cases, congestion was less than usual.

The lesson here is that traffic is not an inalterable and irreducible quantity dictated by nature, its actually very dynamic and elastic. People readily change their travel behavior in response to the availability of road capacity. That’s the essential insight behind the science of “induced demand“–the observation that newly expanded roadways quickly fill to capacity. And this is its mirror image: “traffic evaporation.”

Many of the trips on our roadway are discretionary. We can choose to take them at other times, take other routes, combine or forego trips, choose new destinations, or travel by other modes. The traffic we observe at any point in time is not a fixed and inexorable amount that must be “served” but is simply the behavioral response of humans to the set of transportation choices available to them.

The repeated failure of these predicted “carmageddons” to ever occur is powerful evidence that the key tenet of highway planning is fundamentally flawed. Highway departments claim that if we don’t build more roadways, traffic and congestion will increase without limit and we’ll face hours and hours of delay. In reality, that never happens because people adapt their travel behavior to the available transportation system. Widening roads in an effort to reduce congestion isn’t simply futile, its counterproductive. More capacity generates more travel, more sprawl, more pollution, and ultimately more congestion. It’s time to get off this treadmill.