Why predicted gridlock almost never happens and what this teaches us about travel demand

It had all the trappings of a great disaster film: A spectacular blaze last week destroyed a several hundred foot-long section of Interstate 85 in Atlanta. In a city that consistently has some of the worst traffic congestion in the country, losing a key link its freeway system could only mean one thing: Carmageddon. Governor Nathan Deal has declared a state of emergency. The bridge collapse effectively “puts a cork in the bottle,” said Georgia State Patrol Commissioner Mark McDonough. This particular segment of freeway carries nearly a quarter million cars per day. So as the Daily Mail shouted, chaos is coming:

The prospect of gridlock makes for great headlines and local TV news stories, but as it turns out, predictions of terrible traffic in the wake of even major disruptions to the road system are almost never realized.

One of the most famous instances of this phenomena was in Los Angeles. In 2011 and 2012, the state highway department closed a 10 mile stretch of Interstate 405 on several weekends to rebuild overpasses. The media was awash in predictions of Carmaggedon. But surprisingly, nothing of the kind happened. As Brian Taylor and Martin Wachs explain in an article in Access, people mostly avoided taking trips in the area, or chose alternate routes, with the effect that traffic was actually much lighter than normal. They report that “Rather than creating chaos, the first closure greatly reduced traffic congestion.” Taylor and Wachs explain that “crying wolf” about likely gridlock depressed trip-taking in the affected area, but that effect faded as travelers realized things were nowhere as bad as predicted.

You might think that the kind of behavioral effects that keep Carmaggedon at bay only work when its a short closure of a few hours. But even the year-long closure of I-35W in Minneapolis, following the collapse of a highway bridge over the Mississippi in 2007 produced similar results. Travelers quickly changed their routes and travel times, and many people simply stopped taking trips that crossed the river. David Levinson reports that there were about 46,000 fewer trips per day across the river after the bridge collapsed.

You’ll forgive our excessively clinical attitude about this damage–and its going to cost tens of millions to fix–but what we have here is a classic “natural experiment” of the kind economists and students of public policy relish. So what happens when we take a major urban freeway out of service for a couple of months? Are Atlanta commuters in for hours of gridlock every day and grisly commutes? Will the region’s economy grind to a halt as a result? We’ll be watching over the next several months to see.

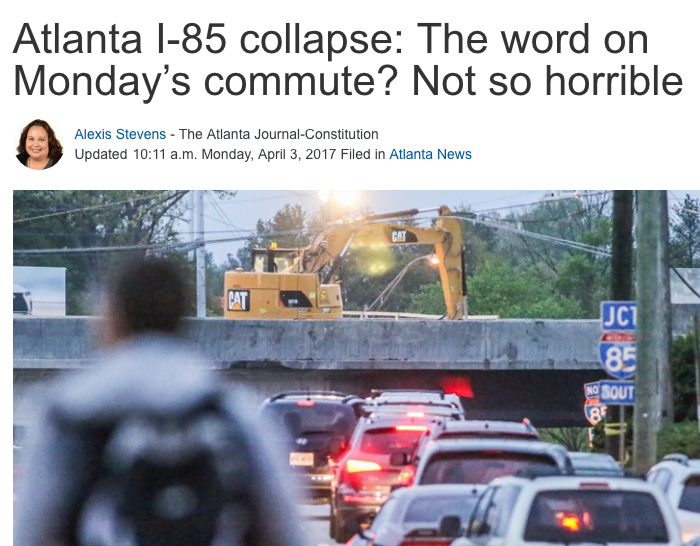

So far, the results are consistent with what we’ve seen in Los Angeles and Minneapolis. Monday morning came, and something funny happened: traffic wasn’t so bad. The Atlanta Journal Constitution reports

And Google Maps showed that late in the morning, traffic looked pretty normal:

So what’s going on here? Arguably, our mental model of traffic is just wrong. We tend to think of traffic volumes, and trip-making generally as inexorable forces of nature. The diurnal flow of 250,000 vehicles a day on an urban freeway like I-85 is just as regular and predictable as the tides.What this misses is that there’s a deep behavioral basis to travel. Human beings will shift their behavior in response to changing circumstances. If road capacity is impaired, many people can decide not to travel, change when they travel, change where they travel, or even change their mode of travel. The fact that Carmageddon almost never comes is powerful evidence of induced demand: people travel on roadways because the capacity is available for their trips, when when the capacity goes away, so does much of the trip making.

If Atlanta can survive for a month or two without a major chunk of its freeway, that’s a powerful indication that more modest steps to alter road capacity don’t really mean the end of the world. If we recognize that traffic will tend to adjust to available capacity, we then end up taking a different view of how to balance transportation against other objectives. For example, this ought to be a signal that road diets, which have been shown to greatly improve safety and encourage walking and cycling, don’t have anything approaching the kinds of adverse effects on travel that highway engineers usually predict. So in the next few weeks, keep an eye on Atlanta: If the one of the nation’s most sprawling and traffic ridden cities can survive the loss of a freeway segment that carries a quarter million vehicles a day, its a strong sign that more modest changes to road systems really don’t have much impact on metropolitan prosperity.