Think riots destroyed #Baltimore? Entire blocks boarded up. pic.twitter.com/OKSnHXMb9f

— Michael Kaplan (@MichaelD_Kaplan) May 1, 2015

Look what the riots did to Baltimore! Oh wait no…These were taken before the riots. Oops. @MayorSRB pic.twitter.com/2iTsnVDf6G

— Chels (@BEautifully_C) April 30, 2015

In the wake of violent protests against yet another apparent police killing in Baltimore, variations of this meme spread rapidly in certain corners of social media. Their message went something like this: Pundits and politicians may think Baltimore’s crisis began with the first brick that hit a window at CVS, but we – the people who live there – know the crisis goes back much further, and much deeper.

With this in mind, there’s some irony to the spate of columnists warning that the disturbances in Baltimore mark a return to the “bad old days” of the mid-to-late 1960s, when a series of violent protests in America’s black neighborhoods held the nation riveted. Those riots, too, were treated as a crisis by pundits who had not applied the term to decades of housing discrimination, or illegal violence on the part of police officers and white civilians.

But using violent protests as a point of analytic departure – rather than the underlying crises that provoked them – doesn’t just (unintentionally) reveal one of the similarities between 1968 and 2015. It also misses a lot of the major differences.

At the Washington Post, Radley Balko has covered some of the ways in which things are much better now. For one, the wave of violent crime that plagued American neighborhoods – and especially ones whose residents were predominantly low-income and black or brown – has receded, even if it remains far too high. Balko reminds us that the U.S. saw 500 fewer murders in 2013 than in 1969, despite the fact that there were over 100 million more people.

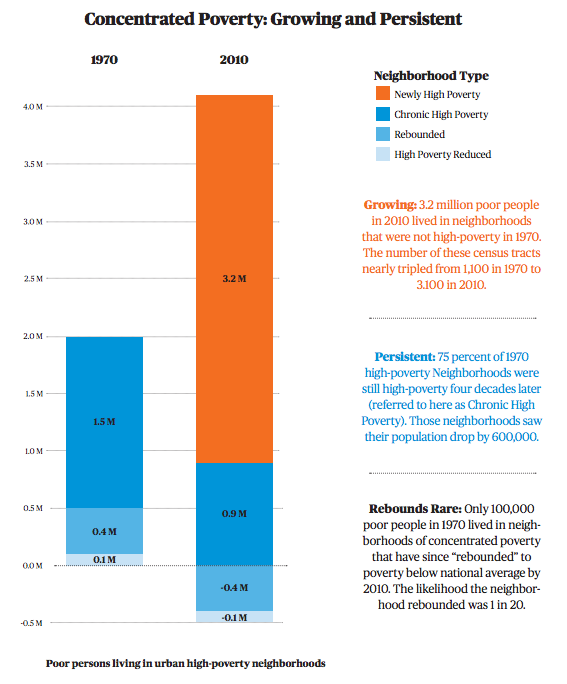

In other ways, things are much worse. As we’ve covered here at City Observatory, concentrated poverty has exploded since 1970, with three times more neighborhoods with poverty rates of at least 30 percent in 2010. And even as crime has declined, the incarceration rate – particularly among black men – has skyrocketed, disrupting millions of lives and leaving communities across the country with millions of “missing” men.

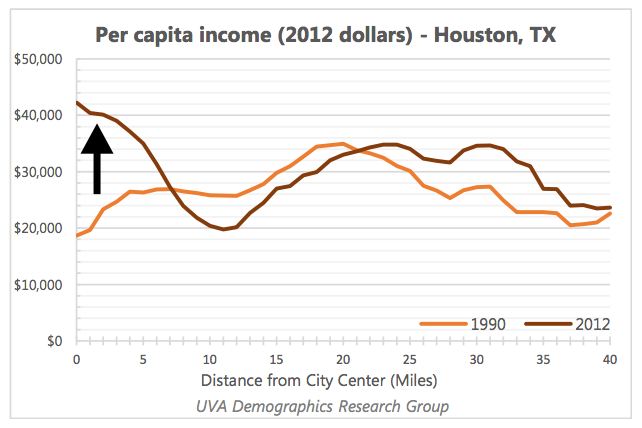

But especially when it comes to the role of cities, the comparisons to 1968 miss the very, very different trend lines of that era. In the 1960s, America was decades into – and had decades remaining in – a period in which wealth, and anyone who had enough of it, was moving as far as it could from urban centers.

For a variety of reasons, those trends have now reversed. The geography of metropolitan wealth is now double-peaked: downtowns and surrounding neighborhoods are catching up to rich outer suburban neighborhoods, and the ring of poverty that separates them is moving further out into outer city neighborhoods and inner-ring suburbs.

Importantly, this movement of middle- and upper-income people and jobs back to center cities has taken place despite the presence, and growth, of intensely concentrated poverty within those very same cities. That is, the prediction of people like Joel Kotkin that the problems of poor neighborhoods in Baltimore will hold back this trend just doesn’t appear to match the evidence.

It is true, of course, that so far reinvestments in places like Baltimore’s Inner Harbor have mostly not translated to meaningful improvements in the lives of residents in struggling neighborhoods. But we believe that the return of wealth to America’s inner cities at least provides a valuable opportunity to make those improvements.

That’s because broadly speaking, the built form of cities – defined as anything from a dense Manhattan neighborhood to the “streetcar suburban” communities in Midtown Memphis – really is a better arena for seeking social justice than most automobile-oriented suburbs.

For one, urban neighborhoods tend to offer a larger proportion of public, rather than private, space. This can take the form of anything from public parks, libraries, and civic centers, to simply a sidewalk. For people who are low-income, that means access to services, amenities, and cultural life that might be denied to them in the suburbs: think of the difference between a city with public pools and a suburb where people only go swimming in their backyards, private athletic centers, or a shared private pool in a gated community.

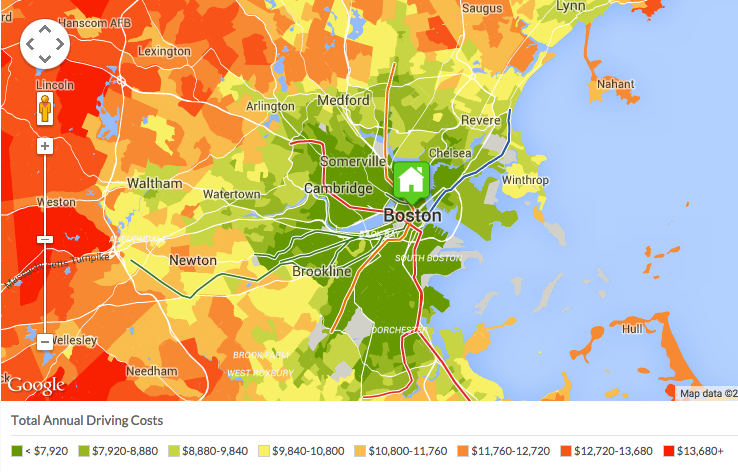

Second, because urban neighborhoods tend to offer a wider range of transportation options – including walking, biking, and public transit – transportation costs are much, much lower. In a city, you can save thousands of dollars a year by not owning a car – money that would be better spent on higher-quality food, your kids’ education, or retirement savings, but which in a typical suburb would instead go to insurance and gas. Even where a family doesn’t want to give up car ownership entirely, moving from one car per adult to one car per household can mean significant savings.

Finally, urban neighborhoods tend to be located in larger municipalities. (This isn’t always true, of course – there are urban neighborhoods in small suburbs and very “suburban” neighborhoods in large cities – but for historical reasons, it generally is.) That means city services can draw on taxes from both high-income and low-income neighborhoods – as opposed to smaller suburban municipalities, where high tax revenues from rich areas feed back into high-quality services for the wealthy, while low-income municipalities struggle to fund services for their poorer residents.

The return of wealth to central cities has the potential to enhance all three of these factors: balancing tax rolls in historically disproportionately poor cities allows those governments to provide better public services and amenities, while creating jobs in central cities, rather than suburbs, allows more people to get to work via affordable transit. On top of that, attracting middle class households back to cities that have gone decades without them creates the possibility of more economically integrated neighborhoods – which, as recent research shows, can lead to more social mobility for low-income residents.

So far, of course, we’re very far from realizing that potential. But that’s a very different failure than the situation cities like Baltimore found themselves in fifty years ago.