The HB 2098 “-2” amendments are perhaps the most fiscally irresponsible legislation ever to be considered by the Oregon Legislature. They constitute an open-ended promise by the Oregon Legislature to pay however much money it costs to build the Interstate Bridge Replacement and Rose Quarter freeway widenings—projects that have experienced multi-billion dollar cost overruns in the past few years, before even a single shovel of dirt has been turned.

HB 2098-2 amendments would:

- Raid the Oregon General Fund of $1 billion for road projects

- Give ODOT a blank check for billions of dollars of road spending

- Allow unfettered ODOT borrowing to preclude future Legislatures from changing these projects and forcing their funding

- Eliminate protective sideboards enacted by the Legislature a decade ago

- Enact a meaningless and unenforceable cap on project expenses.

Oregon’s transportation department is going broke: Its major source of revenue, the gas tax, is in terminal decline, thanks to growing vehicle fuel efficiency and electrification. The agency doesn’t even have enough money to maintain current roads, and has been cutting back on maintenance, and yet is set to embark on an unprecedented spending spree.

The “-2” Amendments will serve as a pretext for ODOT to borrow money to get each of these projects started, regardless of how much the projects will actually cost, and whether federal grants for these projects or toll revenues will cover even a fraction of their cost.

The bill does this because it knows that if legislators were asked to come up with the money for these projects today, by raising gas taxes or other road user fees, there’d be no stomach (or votes). So, instead, they’s simply let ODOT max out its credit cards, and sign construction contracts, and come back to the 2025 Legislature with a giant bill that it will have to pay.

“If wishes were horses, beggars would ride”

The Legislature seems bound and determined to enact into law this old Scottish proverb. Section 3 of the -2 amendments declares the Legislature’s “intent” to borrow $1 billion in General Obligation Bonds, to be repaid over the next couple of decades or more from the state General Fund. Section 11 of the -2 amendments further declares the Legislature’s “intent” to appropriate whatever it ends up costing to build the I-5 Rose Quarter project, with no reference to a specific dollar amount or source of funds.

The -2 amendments to HB 2098 don’t contain an explicit appropriation of funds, or a new source of revenue, or even a specific authorization to issue new debt. Instead, we have just vague indications of intent:

“The Legislative Assembly intends to support the Interstate 5 bridge replacement project through an investment of $1 billion . . ”

“The Legislative Assembly affirms its intent to fully fund the Interstate 5 Rose Quarter Project in the 2024 and 2025 regular sessions of the Legislative Assembly.”

It’s far from clear what the legal meaning of these statements of “intent” have. But the authors of the -2 amendments are trying to have it both ways: they are trying to appropriate money, without actually appropriating money. They’re not actually taking the step to spend these funds (and say where the money will come from) but are trying to commit future Legislatures to making those difficult decisions. It might seem that statements of intent (like legislative resolutions and memorials) are merely legislative window-dressing, with no legal weight. But it’s clear that the Oregon Department of Transportation has other plans.

“Intent” plus debt: Committing future Legislatures to pay billions

Superficially, HB 2098-2 might seem like an empty letter—the Legislature often makes sweeping, feel good statements of intent—but the danger with this one is that it could serve as the basis for the Oregon Department of Transportation to pull out its credit card and borrow hundreds of millions of dollars, based on the vague promise that some future Legislature will pay these bills. And this is no idle speculation: this is exactly what ODOT did with the I-205 Abernethy Bridge Project.

It’s worth spending a minute to review that project. In 2017, the Oregon Legislature adopted a major transportation package, which provided $450 million for the I-5 Rose Quarter project (paid for with a $30 million per year increase in gasoline and weight mile taxes). That package conspicuously did not provide funding for the Abernethy Bridge, but instead the Legislature directed ODOT to come up with a plan to use tolling to pay for I-205 improvements, and to report back with a “Cost to Complete” report that would tell how much this project would cost. In 2018, the Cost to Complete report came in with a $250 million price tag for the Abernethy Bridge. The I-205 project languished for a couple of years, and in 2021, ODOT persuaded the Legislature to adopt HB 3055, which made two significant changes. HB 3055 authorized ODOT to dip into the $30 million per year fund designated for the Rose Quarter project to pay for I-205 (as well as the I-5 Boone Bridge), and also gave ODOT the authority to issue short-term bonds (the public sector equivalent of a payday loan).

In 2022, ODOT used the newly granted authority in HB 3055 to move forward with the Abernethy Bridge Project. First, it told the FHWA that it could build the project entirely without toll financing—thus evading federal environmental review of tolling on the Abernethy Bridge. Second, it took advantage of its short term borrowing authority and the HB 2017 Rose Quarter funding to start construction on the Abernethy Bridge, even though the price tag of the bridge had doubled to $500 million from the number it quoted the Legislature. As a result of ODOT’s action, Oregon is now obligated to pay the full price of the Abernethy Bridge project, presumably through the HB 2017 $30 million appropriation and toll revenues.

It’s likely that the Abernethy Bridge project will use up all of the $30 million per year available from HB 2017, leaving little or nothing to pay for the I-5 Rose Quarter project, which meanwhile, has tripled in cost to as much as $1.45 billion—and which still faces major questions over its design.

A Blank Check for the Highway Lobby

Combining Oregon DOT’s short term borrowing authority from HB 3055 (its basically unfettered ability to get a payday loan of hundreds of millions of dollars), with a statement of “intent” that the Legislature will some day deliver whatever money is needed for the I-5 Interstate Bridge Replacement Project and the Rose Quarter freeway widening is likely all ODOT needs to get these projects started. It will issue perhaps $500 million in such bonds, covering the initial interest and principal repayments from its current revenue and with the assumption that it will ultimately refinance the balance of the costs in balloon-mortgage fashion with the “intended” funding from some future Legislature.

And when these blank checks are filled in, the numbers will be very large. The Interstate Bridge Replacement Project’s estimated cost has risen from a supposed maximum of $4.8 billion in 2020, to a new maximum of $7.5 billion today. Similarly, the cost of the I-5 Rose Quarter project was sold to the 2017 Legislature as being $450 million. The latest estimate now runs to $1.45 billion–and that figure is already out of date. And these are just preliminary, pre-construction estimates; if past experience is any guide, both of these projects will both end up costing significantly more once actual construction begins.

Once started, both the IBR and the Rose Quarter projects are designed in such a way that it may be impossible or prohibitively expensive to reduce their scope. The IBR is planned as a fixed, high-level crossing that will necessitate lengthy elevated viaducts and the rebuilding of freeway interchanges (which constitute a majority of project costs). Once the bridge is started to that design, it will be difficult to reduce its cost. Similarly with the Rose Quarter project, where its 160 foot width dictates excavation costs and drives up the cost of proposed covers. If ODOT starts these projects, the state will be stuck with bloated, over-sized projects it can’t change. And that, as we have long said, is the point: This is the classic Robert Moses strategy of “driving stakes and selling bonds” and putting the Legislature in a position where it has no ability to control what the highway building agency does. That was tragic and stupid when Moses first did it in New York in the 1930s; it is even more tragic and stupid today, when we know with a certainty that highway widening doesn’t reduce congestion, that it destroys the fabric of urban neighborhoods, and worsens air pollution and climate destruction.

Eliminating the Sideboards

In legislative parlance, “sideboards” are conditions or limits included in legislation to prevent bad things from happening. In 2013, the Oregon Legislature was considering spending $450 million for the I-5 bridge project, and after lengthy debate, it approved a series of such sideboards, trying to limit the cost of the project (more about that in a minute), and then also prohibiting the state treasurer from issuing any bonds for the project until after the Washington has contributed its share of the project’s costs, the federal contribution to the project was clearly committed, there had been prepared an independent financial plan for the project, and the state had conducted an “investment grade analysis of possible toll revenues. All of those provisions are still codified in Oregon Law (Section Chapter 4 of Oregon Laws 2013).

And every one of those sideboards is eliminated, without acknowledgement. Even the amendment’s “Staff Measure Summary” which is meant to disclose to Legislators the impact of the bill only cryptically and opaquely says:

“Repeals sections of House Bill 2800 (2013).”

Project Cost “Cap”–a legal limit from “Camelot”

We already know that a project cost cap is meaningless and unenforceable. We already have such a cap! It was enacted into law a decade ago and officially limited the total cost of the IBR to not more than $3.4 billion. 2013 Oregon Laws, Chapter 4, (Enrolled House Bill 2800) reads:

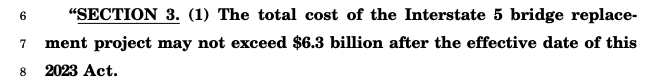

Conveniently, the “-2” amendments to HB 2098, without any fanfare, simply repeal this limit. In its place, is an entirely new limit, which is worded identically–except of course that now the cost is more than twice as much.

As the Oregonian‘s “Politifact” reporters noted when they looked at the original so-called “cost cap” provisions for the Columbia River Crossing adopted by the Oregon and Washington Legislatures a decade ago, the caps are meaningless and unenforceable.

. . . if legislators greenlight the CRC, the state could ultimately owe more than $450 million on its share of the bridge. But setting a cap on the project or limiting Oregon’s share with legislative riders won’t stop that. And thanks to the agreement between Oregon and Washington to pay for the bridge jointly, if Oregon ever needs to pay more, Washington would need to join in.

PolitiFact Oregon doesn’t do prophecy. We can’t say whether the bridge will be over budget — as much as history might tempt us to offer a guess.

What we can say is that the Washington toll rule won’t matter. The Washington Legislature’s cap won’t matter.

The Legislature has no more ability to prescribe the cost of this project by edict, than it has to regulate temperature or rainfall. Yet, the author’s of the “-2” amendments are simply performing a refrain from Camelot:

It’s true! It’s true! The crown has made it clear.The climate must be perfect all the year.A law was made a distant moon ago here:July and August cannot be too hot.And there’s a legal limit to the snow hereIn Camelot.The winter is forbidden till DecemberAnd exits March the second on the dot.By order, summer lingers through SeptemberIn Camelot.

Crossing the Rubicon: Raiding the General Fund for Road Projects

For the better part of a century, Oregon has prided itself on its “user-pays” transportation finance system. Oregon was the first state to adopt a gasoline tax to pay for roads, and has observed a long tradition of having a “State Highway Fund” that is strictly segregated from other tax revenues and dedicated exclusively to paying for roads. For the first time, the -2 amendments to HB 2098 would raid the General Fund to the tune of $1 billion to pay for a road project–which we’ve pointed out at City Observatory chiefly benefits residents of Washington State, as 80 percent of daily commuters and two-thirds of all bridge users live across the border in Washington.

Repealed Sideboards from HB 2800.

Here’s the language that would be repealed, featuring the provisions that weren’t disclosed in the text of the “-2” amendments or the Staff Measure Summary.

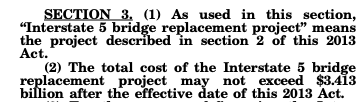

SECTION 3. (1) As used in this section, “Interstate 5 bridge replacement project” means the project described in section 2 of this 2013 Act.

(2) The total cost of the Interstate 5 bridge replacement project may not exceed $3.413 billion after the effective date of this 2013 Act.

(3) For the purpose of financing the Interstate 5 bridge replacement project, the State Treasurer may not have outstanding, at any one time, bonds in an amount exceeding $450 million of net proceeds, plus an amount determined by the State Treasurer to pay estimated bond related costs of issuance, for the purpose of funding Oregon’s share of the aggregated contribution to the project from Oregon and the State of Washington as described in the Final Environmental Impact Statement submitted to the United States Government for the project. It is the intent of the Legislative Assembly that moneys from the United States Government or toll revenues be used to directly fund the project, be used to repay other borrowings for the project or be pledged alone or with other security to lower the costs of other borrowings for the project

(4) The Department of Transportation may not request and the State Treasurer may not issue any bond to finance the Interstate 5 bridge replacement project unless:

(a) No later than September 30, 2013, the State of Washington has appropriated, authorized or committed sufficient funds to:

(A) Satisfy the United States Department of Transportation requirement for a proposed full funding grant agreement application; and

(B) Meet the requirements of the finance section included in the project’s Final Environmental Impact Statement published on September 11, 2011, and endorsed by the Federal Transit Administration and the Federal Highway Administration in the record of decision dated December 7, 2011;

(b) The United States Department of Transportation has submitted a full funding grant agreement application, in an amount of at least $850 million of Federal Transit Administration funds, for congressional review;

(c) The State Treasurer has participated in and approved the findings of an investment grade analysis of toll revenues associated with the project’s application for a loan from the Federal Highway Administration’s Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program, and provided for ongoing financial analysis of the project;

(d) The State Treasurer has reviewed and approved a comprehensive financing plan for the project, after making written findings that there are sources of funds committed by contract or law or otherwise obligated that are reasonably expected to be available and that will provide sufficient cash flows to pay the estimated costs of the initial phase of the project described in the full funding grant agreement without revenues from borrowings in addition to those described in subsection (3) of this section; and

(e) The United States Coast Guard has issued a general bridge permit for the main channel of the Columbia River for the project.

Proposed Amendments to HB 2098-2

If the author’s of the “-2” amendments were being candid, there’s what their amendments should actually say:

- This act shall be known as the Blank Check, Pass-the-Buck, Cost-overrun, Send the Bill to our Kids Act of 2023.

- The Legislature finds and declares that it doesn’t have the guts to pay for any of the billions of freeway widening projects ODOT is pursuing, and that it is unwilling to raise gas taxes to pay for them.

- The Legislature intends that ODOT borrow billions of dollars based on vague “intentions” that the Legislature will miraculously find the will and the money to pay for these projects two or four or six years from now, and that ODOT should go ahead and borrow the money to get these projects started so that the Legislature will have no choice but to raise money someday in the future.

- The Legislature intends that it will spend billions of dollars today to widen freeways that will increase car dependence and greenhouse gas emissions, and send the bill to future generations of Oregonians, who will also have to deal with the increasingly devastating effects of climate change.

- The Legislature finds and declares It is powerless to do anything to limit ODOT cost overruns and that it will simply sign a blank check to ODOT for whatever amount of money it wants to spend on the Rose Quarter project. that even though it approved the I-5 Rose Quarter project at a cost of $450 million in 2017, and that the cost has tripled to as much as $1.45 billion now, that it will fully fund whatever ODOT decides to spend on this project.

- The Legislature finds and declares that the reasonable and prudent “sideboards” adopted by the Legislature a decade ago, when the state’s expected contribution to the IBR project was only $450 million, should be eliminated.