When we talk about the costs and consequences of car-dependent urban development, we often talk about hard economics and climate science. Spread-out neighborhoods divided by big, pedestrian-hostile roads force people to spend more on transportation than they would in a place where many trips could be taken by foot or transit. In high-demand cities, relatively lower-density development can lead to a “shortage of cities” that pushes housing prices up, encourages economic segregation, and leads to lower intergenerational economic mobility. And these urban forms are also highly correlated with more greenhouse gas emissions, worsening the threat of climate change.

But people also experience their neighborhoods as communities—as places where people gather, interact, and enrich each others’ lives. In our 2015 report “Less in Common,” we explored the ways in which increasing auto-centric development has degraded this aspect of our urban life. Now, as we did with our report “Lost in Place,” City Observatory and Brink Communication have put together an infographic to make these important ideas easy to share—and as always, this and all of our work is licensed under Creative Commons-Attribution, so feel free to incorporate it in your own presentations or reports.

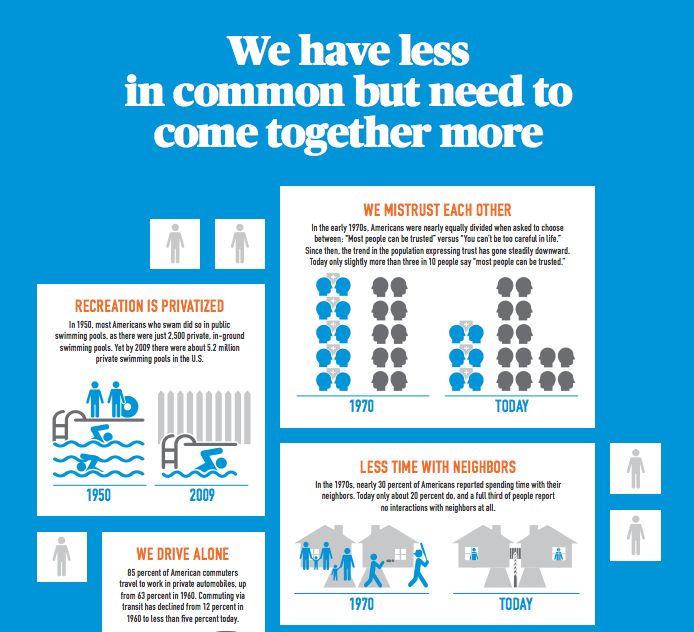

The infographic illustrates many of the key findings of “Less in Common,” which illustrate ways in which increasing sprawl has weakened our communities, and show how a broader trend of Americans living more widely separated private lives has created a space for smart urban planning to strengthen the public realm.

Perhaps one of the clearest connections is in recreation: While Americans who went swimming in 1950 would probably go to a community pool, since then, the number of private, in-ground pools has increased from 2,500 to 5.2 million in 2009, as large-lot zoning and the construction of highways far into the suburban periphery has essentially subsidized the consumption of private land, at the expense of public facilities. These trends are mirrored in how we get around, relying more and more on cars cars as a mode of transportation, replacing walking and public transit—modes in which, outside a sealed, private machine, you might actually interact with neighbors or others. In fact, while about 30 percent of Americans reported spending time with their neighbors in 1970, that number was down to about 20 percent today.

This privatizing of public life has also encouraged further segregation of neighborhoods by economic status, a trend that has been well documented, and which we have explored at length at City Observatory. Rich and poor Americans have become more spatially divided as we sort into high income and low income neighborhoods. While only 15 percent of Americans lived in rich or poor neighborhoods in 1970, by 2012, that figure was up to 34 percent.

The erosion of the civic commons also has a profound impact on economic opportunity: In regions with more economic segregation, children from low-income households are much less likely to be able to improve their income status as adults.

As the rapper Ice Cube told National Public Radio earlier this year, reflecting on the school integration policies of his childhood:

I liked it because I was being bused with a lot of my homies. So we was, like, all going out there, and then it was a lot of different neighborhoods. So it was, like, buses from all these different neighborhoods all converging on this white school. And it was kind of cool because we had a chance to see different things, different people, have different conversations, hear different music and just get a chance to see that the world was bigger than Compton, South Central or, you know, whatever. You know, so we had a chance to really kind of open our horizons…

In other words, the strength of our public spaces and institutions is crucial both for educational and economic opportunity, as well as expanding our sense of collective potential and identities. That’s something we should all be able to get behind.