The soon-to-be released Rose Quarter I-5 Revised Environmental Assessment shows that ODOT is already reneging on its sales pitch of using a highway widening to heal Portland’s Albina Neighborhood.

It trumpeted “highway covers” as a development opportunity, falsely portraying them as being covered in buildings and housing—something the agency has no plans or funds to provide.

The covers may be only partially buildable, suitable only for “lightweight” buildings, and face huge constraints. ODOT will declare the project “complete” as soon as it does some “temporary” landscaping. The covers will likely be vacant for years, unless somebody—not ODOT—pays to build on them.

ODOT isn’t contributing a dime to build housing to replace what it destroyed, and its proposed covers are unlikely to ever become housing because they’re too expensive and unattractive to develop.

For years, OregonDOT has been pitching its plan to widen the Interstate 5 freeway through Northeast Portland as a way of repairing the damage it did when it built the freeway through the state’s largest African-American neighborhood in the 1960s. In theory, freeway covers would provide building sites, for things such as housing. But there are real questions as to whether ODOT is serious, or whether the covers are deceptive “woke-washing” of the freeway widening.

In the past few days, we have obtained a copy of the soon-to-be released Revised Environmental Assessment for the I-5 Rose Quarter Freeway widening, a $1.45 billion project pitched as “restorative justice” for the Albina neighborhood. The revised assessment was required because of the project’s substantial redesign in the past two years and in part because community opponents, led by No More Freeways, prevailed in a lawsuit challenging the project’s original environmental assessment; the project’s earlier “Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) was withdrawn by the Federal Highway Administration).

The Revised Environmental Assessment shows that the covers are, at best, a half-baked policy. Though ODOT has enlarged the size of the covers under its new “Hybrid 3” alternative, it is now making it clear that it won’t do anything to pay the costs of actually building anything permanent on top of the covers. Instead, that task—and its funding—will be left to some unspecified future time, to be led and paid for by the City of Portland. This is clear evidence of the hollowness of ODOT’s promises of restorative justice: they have no commitment to seeing anything actually gets built on these highway covers.

Promises, promises: A history of misleading images of developed highway covers

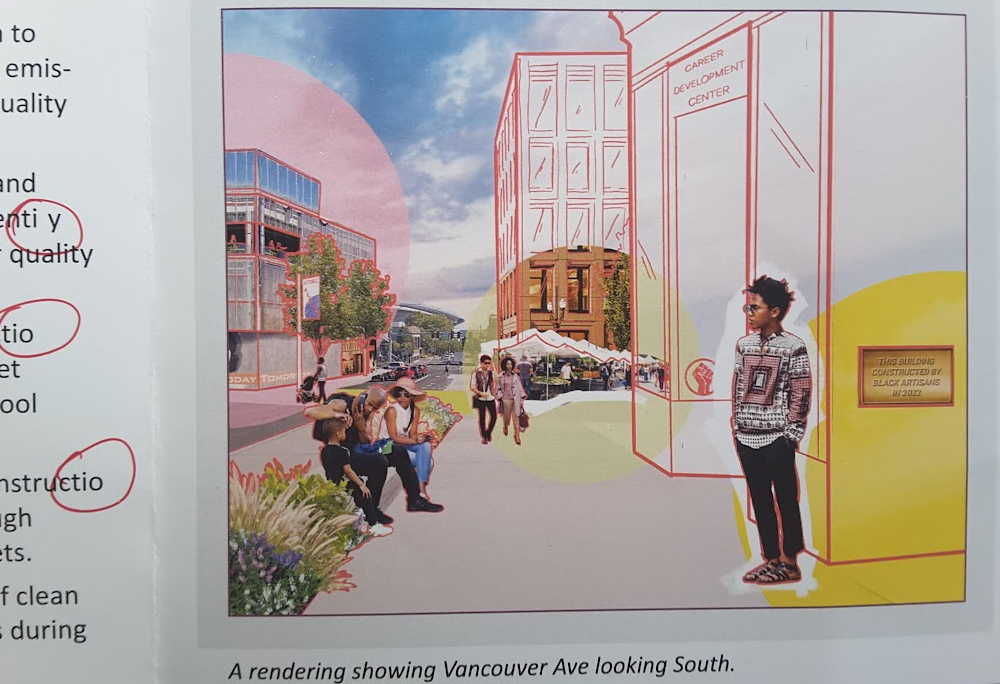

ODOT has repeatedly traded on the idea that the Rose Quarter wasn’t so much a freeway as a reparations project. It has consistently published fictional images of possible housing, commercial buildings, offices and community centers on top of the freeway covers. ODOT consultants touted the importance of building housing to restore community wealth. For example, its study of the “Hybrid 3” alternative depicted hundreds of housing units, and buildings housing important community facilities on top of covers. ODOT’s promotional material, mailed to every household in the project area, prominently featured a fictional “Career Development Center” atop a highway cover—but no illustration of the freeway it intended to widen. (The brochure itself was replete with typos and misspellings, as well as purely imaginary and unfunded buildings).

An ODOT Rose Quarter Project Brochure: A young Black man stands in front of a building labeled a “Career Development Center,” carrying a plaque stating: “This building constructed by Black artisans in 2022.” It’s a nice thought, but such a building is not part of what ODOT will build or pay for. Nor, in fact, are any of these buildings.

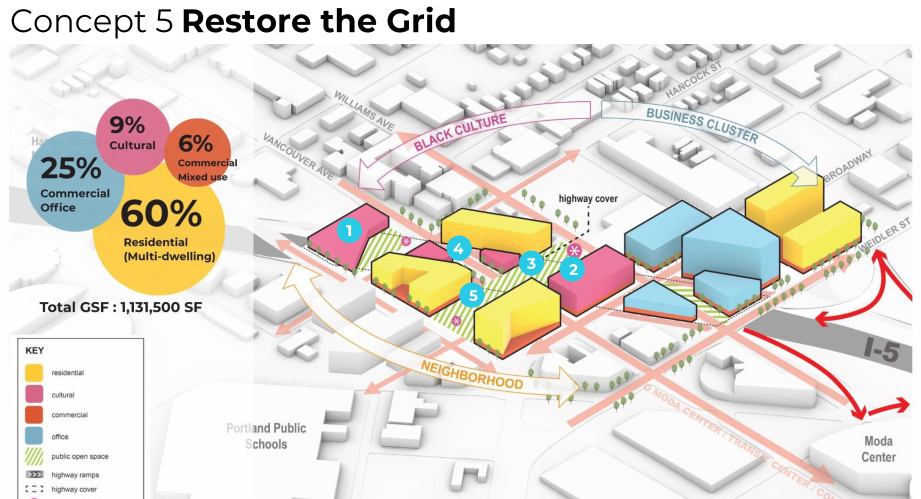

ODOT’s highway cover consultants created the illusion that apartment buildings (the yellow legos on this diagram) might be part of the project’s covers. Building such apartments would cost between $160 million and $250 million, and ODOT is providing no funding for any such construction.

Housing and other improvements have disappeared from the new Environmental Assessment

In its revised Environmental Assessment the Oregon Department of Transportation is finally conceding that it isn’t going to do anything to actually build something on the covers. The pictures of lego housing, wireframe multi-story buildings and “career development centers” it has featured in earlier public relations materials have been erased. In their place is a vague, impressionistic watercolor illustration, and some evasive bureaucratic prose indicating that somebody else, not ODOT, will actually develop the covers—maybe, someday.

ODOT’s already making it clear that they’re not providing a dime to build anything on the covers, and that they expect the City of Portland to pay. What ODOT’s planning are covers with a side of greenwash: They have an artists illustration of the covers with some landscaping and a revealing caption: Artistic rendering reflects a potential immediate use of the cover should future development led by the City not be ready upon project completion.

They elaborate on this in the text of the Revised Environmental Assessment

ODOT anticipates programming interim uses on the highway cover for the time period between Project completion and when the City-led development process would be implemented

The “interim uses” include a laundry list of possibilities: landscaping, plazas, picnic areas, signs and other temporary items which would be removed at some unspecified future time.

Here’s what this means:

- ODOT doesn’t anticipate constructing anything permanent on the covers

- Even this illustrated use is only an artist’s rendering, not something ODOT is committing to do.

- There is no timetable for actual development on the covers

- Development and financing said development is up to the city, not ODOT

- ODOT regards project completion as occurring when the covers are built: the buildings on the covers are not part of the project.

Residents of Albina should be familiar with this “somebody else will take care of this later” approach to restoring the neighborhood. In the 1970s, the city’s urban renewal agency demolished parts of the neighborhood including the commercially vibrant Hill block, for the possible future expansion of Emmanuel Hospital. For nearly four decades, that block has stood vacant. A city process begun in 2017 has yet to yield a definitive plan, and the block remains in an “interim” use. No one should doubt that the same fate awaits the un-funded and difficult to develop freeway covers, if they are ever built.

Not so buildable after all

ODOT has promised that the covers will be buildable, but the Environmental Assessment has a lot of conditions and caveats as to what constitutes “buildable.” Only a portion of the project would be suitable for buildings taller than 3 stories. And any buildings anywhere on the covers would be highly constrained.

For example, blocks at the south end of the cover (shaded blue) which could theoretically hold “lightweight” six story buildings are all bisected by busy traffic streets (Broadway, Weidler, Vancouver & Williams). The cover at the North end of the project (bordered by Flint & Hancock, the two lower traffic streets) is suitable only for 3-story max buildings (and even these also have to be “lightweight”). Nothing in the Environmental Assessment defines a “lightweight” building. The caveats also make it clear that building six story buildings would require additional “modifications to bridge type and roadway profiles.” There’s no indication that these changes would be undertaken as part of the Rose Quarter project.

As a result of these limitations and constraints, the covers themselves will likely be difficult or prohibitively expensive to build anything on. The text accompanying the report acknowledges that while these structures might somehow be able to support multi-story buildings, it won’t be easy.

The highway cover would be designed to accommodate future multi-story buildings. Due to span length and site constraints, design would constrain building size, location, type, and use on portions of the cover. Figure 2-7 shows the cover parameters. Generally, buildings up to three stories could be accommodated throughout the highway cover. Buildings of up to six stories could be accommodated, with strict design constraints, . . .

So, in theory, you could build some kind of multi-story building, but it might have to be small, it couldn’t be built just anywhere on the cover, some kinds of buildings and uses wouldn’t be allowed, plus the building would have to be “lightweight”—whatever that means—and all this would be subject to “strict design constraints.” But none of this is ODOT’s problem, because it isn’t going to fund or build anything permanent on the covers.

Covers don’t restore the neighborhood

ODOT is trying to peddle the false notion that simply decking over a widened freeway will somehow offset the damage that the freeway has done to Albina. It won’t. The covers themselves are likely to be too expensive and too unattractive as building sites. No one will want housing in the middle of a car-choked intersection.

What ODOT’s framing misses is that what destroyed the neighborhood was not merely the construction of the freeway, but the flood of vehicles it produced. Prior to the construction of the freeway there were hundreds of houses, and that the gridded, walkable fabric of Albina was very much intact. It wasn’t simply the the roadway and overpasses that transformed the area, it was the flood tide of car traffic that rendered much of the area inhospitable to residential inhabitation. As we’ve documented at City Observatory, these ODOT highway projects led to the loss of hundreds and hundreds of housing units and led to a decline in population in Albina from more than 14,000 in 1950 to about 4,000 in 1980. This is part of a national pattern in which freeway building led to the systematic depopulation of urban neighborhoods. Abundant research now shows that building freeways kills urban neighborhoods–and not just by demolishing housing, but by creating car-dominated landscapes: the closer your city neighborhood is to a freeway the more population it lost in the last half century. And because ODOT isn’t contributing a dime to actually build any housing, they’re depending on the city or private developers to build housing. This project doesn’t add anything to their interest or ability to provide housing. The neighborhood is not limited by a lack of vacant or greatly under-utilized land. Adding a couple blocks of enormously expensive and difficult to develop land in an unattractive location does almost nothing to change how much housing will be built in Albina.

No one should imagine that the Oregon Department of Transportation is anything other than a group of woke-washing grifters. Their only real interest in the Rose Quarter is widening the roadway, not repairing the massive damage they did to the neighborhood. A bare-bones, barely buildable freeway cover does essentially nothing to eliminate the real harm inflicted here: the eradication of hundreds of housing units and the transformation of a dense-walkable urban neighborhood into a car-dominated landscape. That won’t change under this ODOT plan.