Well-educated young adults are increasingly moving to city centers

Real estate search activity shows no decline in interest in city living due to the pandemic

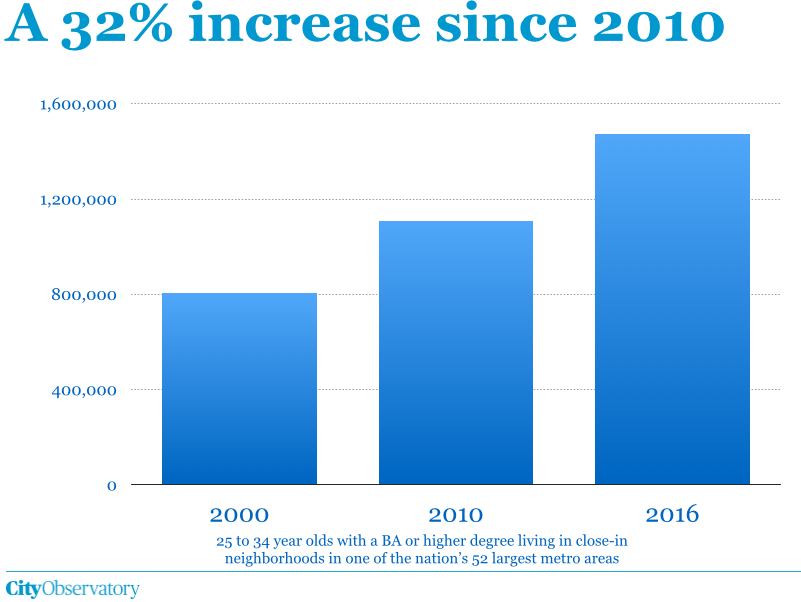

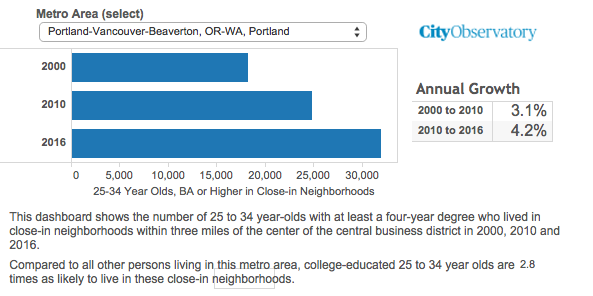

Our new report—Youth Movement: Accelerating America’s Urban Renaissance—confirms a powerful and still growing generational shift toward urban living. Increasing numbers of well-educated young adults are living in close-in urban neighborhoods in and near the downtowns of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas. Since 2010, the number of college-educated young adults living in dense, urban neighborhoods has increased by nearly one-third.

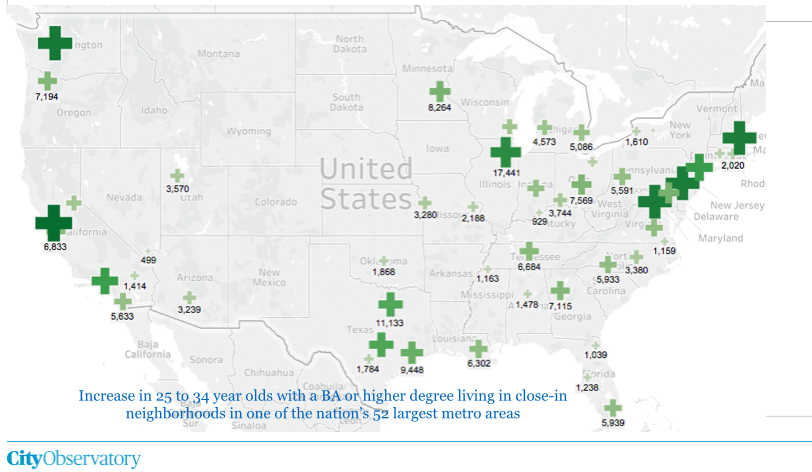

That trend is both pervasive and accelerating. The number of college-educated 25- to 34-year-olds living within three miles of the center of the central business district increased in every one of the nation’s 52 largest metropolitan areas since 2010. And the rate of growth of this demographic in these dense, central neighborhoods was faster since 2010 than in the previous decade in four out of five metropolitan areas.

The increased number of these well-educated young adults living in these neighborhoods is the principal reason for the increase in population in these areas in the past decade. The increase in the number of 25- to 34-year-olds with a four-year degree accounts for a majority of the increase in population in these neighborhoods since 2010.

Our CityReport details our methodology and findings. In addition, you can look up data for your city’s performance on our dashboard.

Fleeing the city? Your internet search history says otherwise

The popular press, and even some urbanist media, is awash at the moment with tales that everyone will abandon cities to avoid Covid-19. It’s easy to make the claim that the Coronavirus changes everything, as in any time of crisis people chuck data out the window and trade heavily on fear and anecdotes. An urban exodus makes a great eye-catching, click-grabbing headline, combining a pandemic prediction with a long American tradition of anti-urbanism, the “teeming tenements” view of cities as overcrowded and unhealthy. Never mind that study after careful study has shown no connection between urban density and Coronvirus infection rates (indeed some of the densest cities—Tokyo, Hong Kong, Taipei, Vancouver and San Francisco, have had among the lowest rates of reported cases), “fleeing the city,” is a journalistic favorite right now.

Generally these stories are based on anecdotes some individual or couple saying they’re planning to leave a big city for its suburbs, with the decision prompted by virus fears. Because people are always moving into and away from cities, individual anecdotes tell us nothing. A far better and more broadly grounded source of information comes from real estate searches. In the past decade, real estate has moved increasingly on-line, and searching for new apartments and houses leaves a data trail that tells us just where people are looking.

Data gathered at the height of the pandemic shows—contrary to the popular stories—that interest in city housing not only hasn’t waned, if anything it has accelerated. Zillow reports that the market share of real estate searches in cities increased in 29 of 35 markets in April 2020, compared with pre-pandemic conditions. Similarly, ApartmentList.com found no decline in search activity for New York City, headlining its analysis, “The pandemic is not scaring renters away from New York.” Zillow economist Skylar Olsen concluded:

While many have predicted “urban flight” we see no such evidence in search activity on Zillow, where the suburbs are actually experiencing a falling share of national search traffic even on homes for rent. Our past research and that of other economists on natural disasters and other traumatic events, really don’t support the idea that our preferences change that fast or that we hold onto the anxiety after the risk has passed.

A panicked prediction that the pandemic will produce urban flight makes for great headlines, but it doesn’t square with the data on what people are actually doing. If our collective interest in city housing hasn’t diminished at all, even in the worst days of the pandemic, there’s every reason to believe that the accelerating trend of movement to cities by well-educated young adults is still very much in place.

Still: A shortage of cities

In some cities, the rate of growth in the young adult population has slowed in the past decade. That’s led some observers to conclude—erroneously in our view—that this signals disenchantment with cities. The cities that have experienced slower growth—such as New York and San Diego—are the ones that have done the least to build new housing, and which consequently have experienced rising rents. When someone claims that a migration of people away from cities because of high rents signals a disenchantment with urban living, they’re getting the story backwards. As Governing’s Alan Ehrenhalt (author of The Great Inversion) writes:

Cities become expensive because people do want to live there. They get even more expensive when there’s not enough good living space to meet the demand. That’s pretty much the whole story. Virtually every attempt to make it more complicated is, well, an unnecessary complication. Why the demand exists, especially among millennials, is a legitimate question. But it doesn’t change the fundamentals.

The fact that young adults are moving to cities even in the face of housing shortages and rising rents is both a signal of the underlying strength of this trend and a reminder that we need to do much more to expand housing in these high demand locations. If we want cities to be equitable and inclusive, expanding housing supply well help keep housing affordable and minimize displacement.

Optimism for the future of cities

Asking people to imagine the future of cities in the midst of a pandemic is like asking people their opinions of swimming in the ocean as they’re exiting the premiere of Jaws. In times of crisis and with overwhelmed by a traumatic event, we tend to deeply discount well understood facts and long-established trends.

It’s worth noting that cities have, throughout history, encountered and overcome challenges like the Coronavirus. The decade of the 1920s, which immediately followed the nation’s last pandemic (the so-called Spanish Flu of 1918-1919, was one of the greatest eras for American urban expansion. In the 19th century, clean water, improved sanitation and urban parks, all made cities healthier places to live.

More recently, cities have flourished in the face of trends that soothsayers said would lead to their demise. We were told in the 1990s that the advent of the Internet meant the “Death of Distance” and that everyone would decamp to cheaper bucolic locations, and that after 9/11, no one would want to live in dense cities like New York for fear of terrorist attacks. Instead, the decades since 2000 have witnessed a burgeoning and increasingly widespread move back to the city, led by well-educated young adults. We have every reason to believe that this trend will continue in the years ahead.

Far from being the places we run from, in times of pandemic and in soul-searching over how we treat Blacks and people of color, cities are the places where we will craft the solutions to these and other challenges. As Carol Coletta notes:

“What feels remarkable to those of us who lived through the devastating effects civil unrest had on cities in the Sixties, recent protests seem only to have solidified the feelings of community and the embrace of diversity that come so much more naturally from city living. Clearly, many Americans want to be part of that. It points to a desire to lean in to city living rather than turn away from it.”