Over the last few months, we’ve outlined a number of policy ideas that address the problem of housing affordability by dramatically expanding the number of people receiving some sort of housing assistance. (Low-income people, that is. We think the number of affluent people receiving housing assistance is already pretty high.)

- We suggested taxing the growth in residential property values. Not only might that provide a disincentive to speculation that drives up market prices, but just a one percent tax would have raised $1.6 billion in the Bay Area in 2013 alone—more than five times San Francisco’s historic, but one-time, bond issue for affordable housing under Proposition A.

- We argued for making Housing Choice Vouchers an entitlement. At the moment, less than a quarter of households that qualify for low-income housing assistance actually receive any, because Congress simply doesn’t appropriate enough money. But we could pay for housing vouchers for every single qualifying person just by dropping one kind of housing subsidy—the mortgage interest tax deduction—for people making over $100,000 a year. Actually, that’s not quite true: we’d still have more than $10 billion left over to increase the value of the deduction for the middle class.

- We suggested that, perhaps even better than expanding Housing Choice Vouchers, we could make low-income housing assistance just as easy and automatic as we make upper-income housing assistance. We could put it in the tax code, by creating a refundable housing voucher tax credit.

None of these policies is on the brink of passing in Congress, or any state capitol or city hall. But they’re worth talking about both as a vision for what an equitable housing policy of the future might look like—and also as a contrast to the failure of scale of today’s marquee housing policies.

Local housing subsidies are woefully out of scale with the problem of affordability

As we noted above, less than a quarter of those who qualify for direct federal low-income housing subsidies get them. But when it comes to housing assistance, that’s the good news. Local housing policies—which, for obvious reasons of political scale, are often the focus of neighborhood activists, researchers, and planners—are in even worse shape.

Take inclusionary zoning, or IZ. Details vary from place to place, but typically, IZ requires housing developers to sell or rent some proportion of their units below market rate. In exchange, the city often allows the developer to build more densely than otherwise allowed, as a way of defraying some of the cost of the below-market units. And sometimes the developers have the option of paying a fee into an affordable housing fund, rather than building the units themselves.

Politically, the appeal of IZ is clear. First and foremost, it’s a way of financing housing that doesn’t require raising property or sales taxes. Second, it creates another hurdle for development, which is almost always a popular move in homevoter regimes. And it has great symbolic value: because of the high cost of construction, new buildings are often the most expensive housing in a neighborhood. Including below-market units in new luxury buildings can be a statement about the value of economic integration.

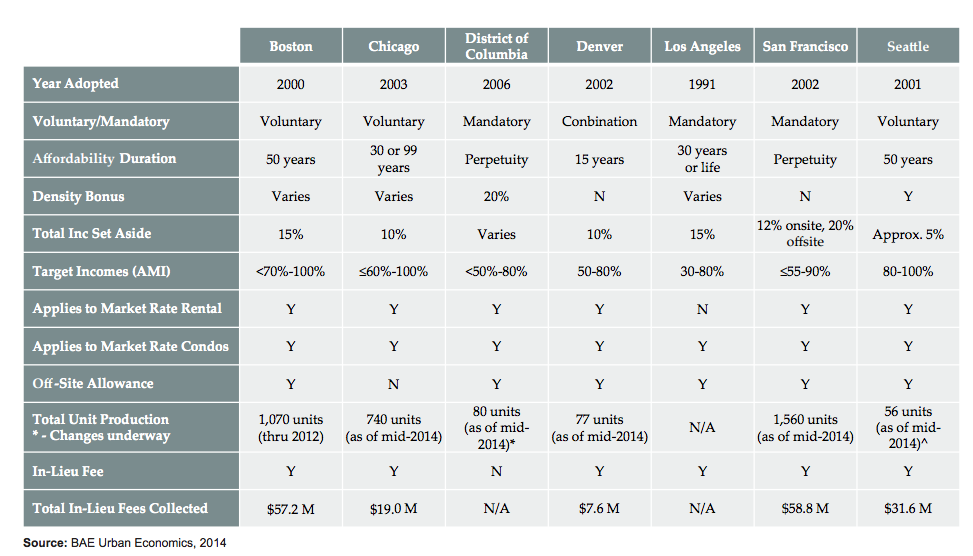

Unfortunately, IZ is more powerful as a symbol than as a way of helping people. A chart published in a New York City Planning Department report last fall makes this point rather eloquently on its own.

There’s a lot going on here, but the most important lines are “Total Unit Production” and “Total In-Lieu Fees Collected.” Washington, DC, for example, created 80 units of affordable housing and collected no money in fees between 2006 and mid-2014. In the DC metropolitan area, 46 percent of renters are burdened by their housing costs. Even allowing for some differences in the District itself (and our quibbles with the 30 percent ratio used to get that number), it’s clear that it would be generous to refer to 80 units of affordable housing—roughly 10 per year—as “token.”

And while DC is a particularly egregious example, the other cities are hardly exemplars themselves. San Francisco looks relatively impressive at 1,560 units—until you realize that’s under 140 units per year in a city of over 800,000 people where median home prices are well above what even upper-middle-class, let alone low-income, households can afford. (Indeed, San Francisco’s “affordable” units go to families of four making as much as $91,700.) Nor do the city’s in-lieu fees make up much of a difference: about $5 million a year, which, according to numbers from Kim-Mai Cutler, might buy about 20 units.

The most successful inclusionary zoning program relied on extremely rapid population growth

Arguably the most successful inclusionary zoning program is in Montgomery County, Maryland, outside DC. Montgomery County’s IZ program, the first in the country, has created over 14,000 affordable units since 1974, or more than 350 a year. But while that’s relatively impressive, it’s hardly met the need: according to the County itself, there are at least 78,000 households that are still cost-burdened. Moreover, Montgomery County’s relative success has been predicated on truly massive population growth, nearly doubling from 564,000 to over a million people from 1974 to 2013. Without that kind of growth, the County would be unable to produce as many IZ units—and, indeed, as population growth has slowed, so has the number of new units. While Montgomery County produced an average of 441 units per year from 1976 to 1999, from 2000 to 2013, it has averaged just 245. Cities that are unable or unwilling to accommodate very rapid market-rate housing construction won’t be able to replicate these results—which still haven’t come close to solving the problem.

None of this is necessarily an argument against inclusionary zoning on its own: local activists may reasonably conclude that this is the best that can be done at the moment. They may similarly decide that the tradeoff of slightly higher market prices is worth creating units at prices below what could otherwise be reached. (Though advocates frequently bristle at the suggestion that inclusionary zoning drives up the price of non-subsidized housing, evidence seems to suggest that it does, at least in markets with high demand and relatively restricted supply—that is, the sorts of markets where IZ is likely to be implemented. And, in fact, when IZ policies are being promoted to local homeowners, advocates sometimes pivot to arguing that affordable housing will be good for property values—in other words, it will make housing more expensive.)

We need to think bigger than inclusionary zoning

But there is no way to argue that inclusionary zoning is coming close to meeting the demand for below-market housing—or, importantly, that it will ever be able to do so. A hundred and forty units per year in San Francisco is not off by ten percent, or fifty percent, or even just one order of magnitude. Moreover, any dramatic expansion of IZ would also involve increasing the amount of private housing development by a similar amount, since IZ depends on piggybacking off of market-rate development—something that would be politically unthinkable in almost any jurisdiction.

In short, IZ needs to be reframed as not a centerpiece, but a minor part of an affordable housing agenda that actually serves everyone who needs help. Advocates need to push government to act on the scale of the problem, and one of the first steps is acknowledging out loud how far we have to go. At a local level, perhaps that can be done with a housing capital gains tax dedicated to funding affordable housing. At a federal level—and it seems more than likely that only the federal government has access to the resources to fully close the gap between the low-income housing assistance we need and what we currently have—expanding Housing Choice Vouchers, LIHTC, or creating something like the housing voucher tax credit could make a big difference. And, of course, broadly affordable housing requires reasonable market prices, too—which requires easing some of the regulations that prevent new housing for new residents and artificially inflate housing costs. Note the findings released just yesterday by the California Legislative Analyst’s Office, which found a much stronger connection between market-rate construction and reduced displacement than inclusionary housing policies.

Again, the point is not that inclusionary zoning is the enemy of affordable housing. It’s that it’s not that great a friend. The fact that IZ may be on the edge of what is politically possible today should not blind us to the fact that the cities and neighborhoods we envision require vastly more ambition.