For four years, the Oregon and Washington highway departments have been pushing a revival of the failed multi-billion dollar I-5 Columbia River Crossing. Their key sales pitch is that the size and design of the project can’t vary in any meaningful way from the project’s decade-old record of decision, for fear of delaying construction or losing federal funding.

Months after choosing a “locally preferred alternative” and after years of warning people that moving away from the 2011 design of the CRC would cause enormous delays, IBR is moving to resurrect a bridge design it ruled out more than a decade ago.

A single level crossing would be significantly wider than the current proposal for a pair of double-decker bridges. Instead, the project would consist of two or three side-by-side, single level bridges, carrying multiple lanes of traffic, light rail trains, bikes and pedestrians all one one level.

The single level crossing would dramatically increase the I-5 footprint, particularly where it crosses the shoreline into downtown Vancouver.

The sudden decision to revive this long-discarded alternative clearly vindicates criticisms raised by independent engineers that the proposed double-decker bridge is too steep; the single level design enables a lower bridge grade. It also shows that the highway department’s claims that the project’s design can’t be changed are simply false.

IBR Suddenly Announces a New Bridge Design

On February 9, 2023 IBR Administrator Greg Johnson off-handedly slipped this little gem into a routine briefing for the project’s community advisory group.

He told them: “We’re looking at a bridge configuration of a single level.”

And Johnson immediately interjected, “that is something that is not new.”

He went on to explain that this gives them added choices for “bridge types and bridge aesthetics.”

Here’s the full quote, and following it a link to the meeting video:

Right now we are on target, we’re on task. And the team is driving forward with technical reports that will go out to the cooperating agencies and partners. We’re also working on within the supplemental we’re working on different technical aspects to make sure that we are covering potential design elements. We are looking at a bridge configuration of a single level. So that is something that is not new, but it is something that we wanted to make sure within the draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement so folks can see the potential impacts of, of what having all of the modes on one level rather than having transit underneath the lane and having the Bike Ped underneath the lane, we have an option that shows them all at one level. So once again, it’s something that we’re studying the impacts of and we will have those two bridge configurations going forward. We know that one level gives us some some some interesting options as far as bridge types and bridge aesthetics that we don’t get with having transit underneath and having Bike-Ped underneath. So we will be looking at that and you will be seeing at an upcoming meeting some renderings that display these potential configurations.

Far from being a minor change, this represents the revival of an alternative design that was ruled out more than a decade ago. It also shows that the IBR project is effectively conceding that its critics, who’ve alleged that its double-decker “modified locally preferred alternative” has a serious safety and cost problem due to its excessive grade and elevated off-ramps. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it shows that warnings that major changes couldn’t be made to the project out of a fear of delays were simply baseless manipulation.

Resurrecting a discarded 15-year old alternative

As we mentioned, IBR administrator Greg Johnson made a point of claiming that the single level design isn’t “new.” It isn’t, it’s quite old, and to have listened to the Oregon and Washington transportation departments, it’s so old that it’s been dead and buried for almost 15 years.

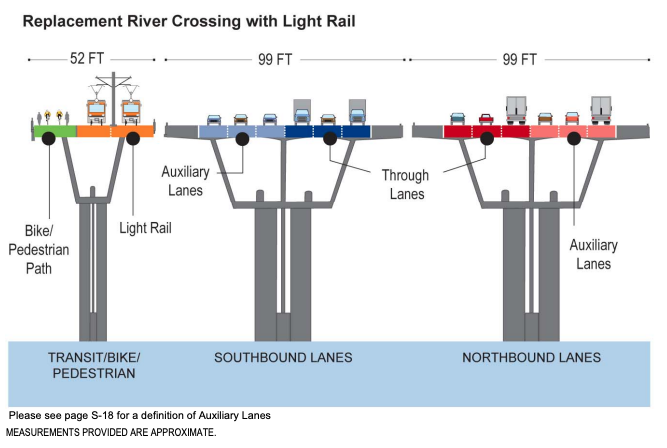

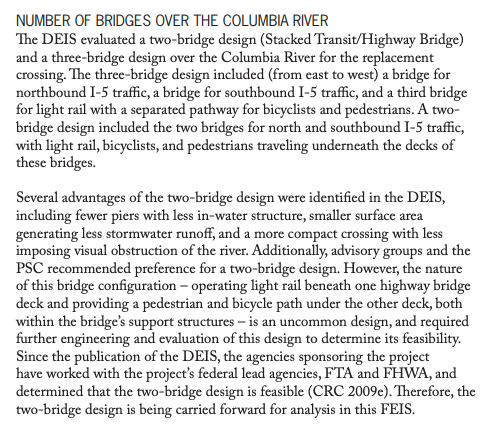

The last official ODOT and WSDOT document featuring a single level crossing design was the 2008 Draft Environmental Impact Statement. It proposed two possible designs for replacement bridges for the current I-5, a pair of side-by-side double-decker bridges (which were chosen as the preferred design), and a trio of single level bridges, as shown here.

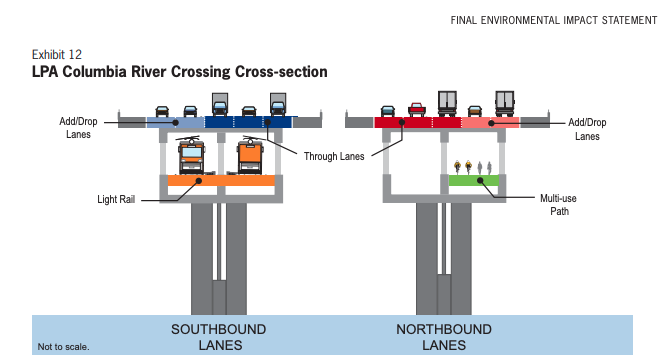

The project’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, issued in 2011, abandoned the single level option, and chose to proceed only with a pair of double-decker bridges (with transit and bike-ped access placed on the lower level of each structure).

The Final Environmental Impact Statement made a strong series of findings rejecting the single level three-bridge design, because it would have more in-river impacts, a larger surface area with more runoff, and would have larger visual impact. [CRC FEIS, Page 2-83]

The single-level design is considerably wider than the two-bridge double-decker design, as shown in this 2007 rendering prepared by IBR.

Apparently we can reconsider the design of the crossing, even at this late date. Ever since he took the job of IBR administrator more than three years ago, Greg Johnson has been warning elected officials not to make any significant changes to the project design included in the 2011 FEIS for fear of delaying it further. An immersed tunnel? More consideration for climate? A lift-span? A narrower freeway? None of these can even be studied, or advanced into the environmental review process, for fear that it will cause some additional delay.

But now, more than six months after theoretically getting buy-off from all of the project’s eight partners for this untouchable design, and spending tens of millions of dollars defining the “modified locally preferred alternative,” Johnson has suddenly decided that he can unilaterally inject back into the discussion an alternative that the project ruled out more than a decade ago.

And make no mistake, changing from double-decker bridges to a single level crossing has significant impacts. It almost certainly means more piers in the Columbia River, and more real estate disruption, particularly on the steadily redeveloping Vancouver waterfront.

A bridge too steep

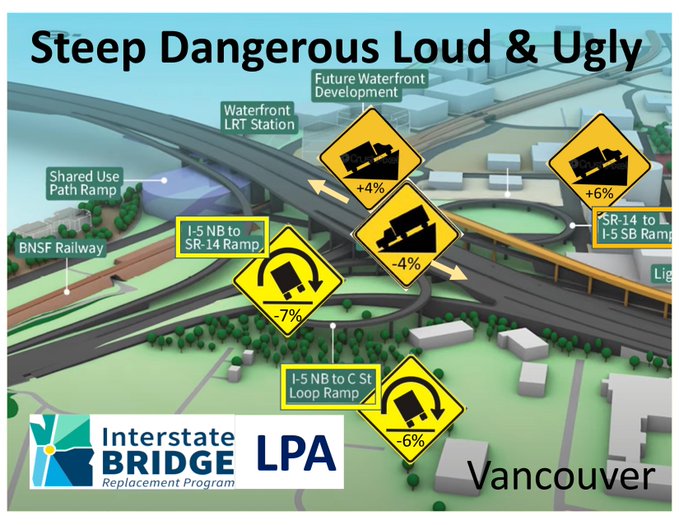

While Johnson claims that the single level design is allows some more aesthetic options, that’s simply misdirection. The real reason that IBR is changing its design at this extremely late date is that it has suddenly realized that one of its most persistent critics was right, all along. For years, engineer Bob Ortblad—who advocates for an immersed tube tunnel crossing—has been pointing out that the proposed IBR bridge design has a dangerously steep grade (nearly 4 percent). This would make it one of the steepest interstate highway bridges in the country. Just to hammer the point home: the Biden Administration just approved a grant of $150 million toward the reconstruction of the I-10 bridge in Louisiana, currently the steepest interstate, to reduce the grade of the bridge to improve safety. It’s also worth noting that the current IBR bridge design violates ODOT’s own standards for interstate highway bridge grades, and would require a design exception. In addition to the safety hazard caused by the bridge grade, the extreme elevation of the roadway requires very steep on- and off-ramps, especially those connecting the bridge with Washington State Route 14, which runs very near the riverbank. Those ramps would have even steeper and more dangerous grades than the bridge itself, a point Ortblad has made graphically:

What Johnson didn’t say—and what’s plainly the real reason for a single level crossing—is that it enables the engineers to lower the roadway by as much as 30 and 35 feet, consequently reducing the overall grade, and importantly, lowering the height of on- and off-ramps at either end of the bridge crossing. The current LPA design calls for a minimum river clearance of 116 feet for the bottom level of each double-decker bridge. The roadway would be on top of the double-decker, about 30-35 feet higher. A single level design could lower the maximum height of the bridge by about 30-35 feet, enabling a lower grade.

Of course, the last thing IBR officials want to do is concede that Ortblad was right—that would damage their disinformation campaign about the merits of the immersed tube tunnel. Instead, they’re suddenly concerned about bridge type and aesthetics.

Why now?

The problems with the bridge grade were first identified more than a decade ago, when the Coast Guard objections let ODOT and WSDOT to hastily redesign the Columbia River Crossing to provide a 116-foot navigation clearance (21 feet higher than what the two highway agencies were planning). ODOT and WSDOT never resolved the questions that were raised about the project’s excessive grade, particularly concerns that steep bridge grades would cause large trucks to slow and impede traffic flow. Following Johnson’s insistent demand that no changes be made to the project defined in the Columbia River Crossing FEIS, IBR has stuck to the steep, double-deck design, never questioning the grade.

But in the past two months, IBR has had to produce a new cost estimate. Embarrassingly, the cost of the IBR project has ballooned by 54 percent to nearly $7.5 billion. To deflect criticism about higher costs, IBR officials testified in December that the project was also subjected to a “Cost Estimate Validation Process,” or CEVP, which the state DOTs advertised as a sure-fire cure for future cost escalation. As we pointed out at City Observatory, no documentation exists for that claimed CEVP. The Washington Department of Transportation responded to a public records request for copies of the CEVP by saying “no documents exist.” Because the agencies have shrouded this process in secrecy we can’t say for sure, but it seems likely that a CEVP meeting likely identified the bridge grade, and expense of elevated interchanges as major cost, schedule and design risks to the project. That would explain why, more than six months after locking down a double-decker “modified locally preferred alternative,” that Johnson and the IBR team are suddenly reviving the discarded single level bridge plan.

It’s not too late to make fundamental changes to the plan

Greg Johnson has cried “wolf” about making serious changes to the IBR project, even as its budget has ballooned by 54 percent in a little over two years, to a total price tag of as much as $7.5 billion. But this latest—and very late—change to the project design is an indication that it’s not too late to fix the fatal flaws in this project. Right now the fatal flaws revolve around its bloated design and price. The reason the project is so expensive has little to do with the bridge structure itself, but rather the extravagant plans of ODOT and WSDOT to widen I-5 for miles on either side of the Columbia River, and rebuild, at much greater expense than the bridge itself, seven different freeway interchanges. If this were simply a bridge replacement—as its name claims—the project would be vastly simpler, less expensive, and likely not controversial.

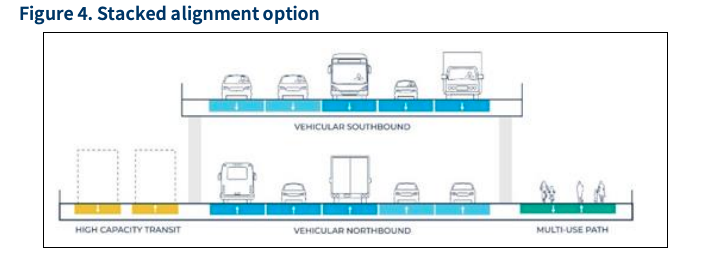

IBR’s Stacked Highway Bridge Alternative (2021)

For reference, we’re providing details of the alternative designs that have been considered by the IBR in the past decade. As noted above, the last time any of the project’s documents mentioned a single level crossing was in the 2008 Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Most recently, in October 2021, when it last listed the alternative bridge designs it was studying, IBR made absolutely no mention of a “single-level bridge”. In fact, the only alternative design they showed was pretty much the opposite: a larger stacked highway bridge, with highway lanes on the upper and lower levels of the double-decker bridge, and with transit and bike-pedestrian routes cantilevered on the sides of the lower level of the double decker.

Nothing but double deckers in 2011 in the Bridge Review Panel Report of 2011

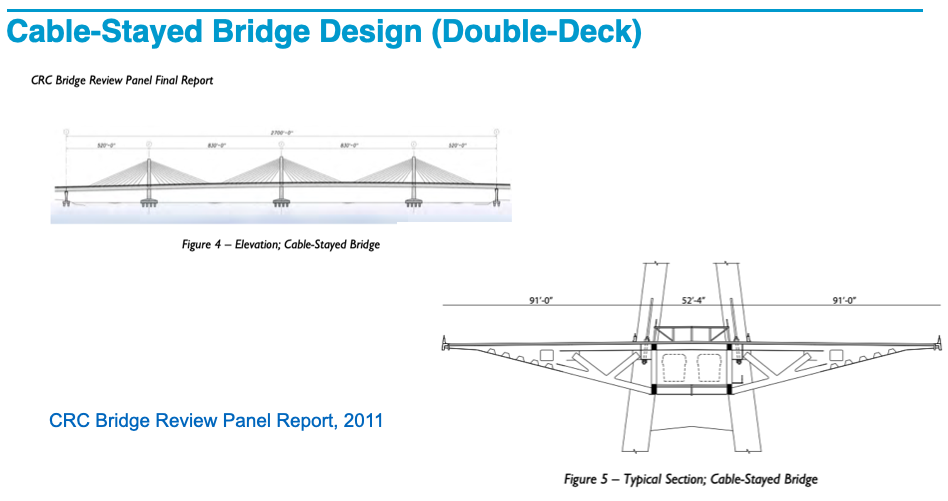

In 2010, an expert review panel appointed by Governor’s Kulongoski and Gregoire found that the proposed “open-web” design being pushed by ODOT and WSDOT was “unbuildable.” That led to the appointment of a “Bridge Review Panel” to quickly come up with a new alternative. They recommended three possible alternatives in their 2011 report: the composite truss design (which became the locally preferred alternative), and two other designs: a cable stayed bridge and a tied arch bridge. All three designs shared a common feature: they were double-deckers with the transit component on a lower level of the bridge. The cable stayed and tied arch designs had elevated bike-pedestrian paths in the center of the bridge, between the north and south bound highway lanes.

Here’s the Bridge Review Panel’s illustration of the cable stayed bridge. The two dotted outlines in the center of the bridge structure on the cross-section illustration are the profile for the light rail transit.

Here’s the Bridge Review Panel’s illustration of the tied arch bridge. Again, the two dotted outlines in the center of the bridge structure on the cross-section illustration are the profile for the light rail transit.