Requiring inclusionary housing seems free, but could mean less money for schools and local services

Last month, the Portland City Council voted 5-0 to adopt a sweeping new inclusionary housing requirement for new apartment buildings. The unanimous decision came with the usual round of self-congratulatory comments about how they were doing something to address the city’s housing affordability problem. No one mentioned that they were also in effect voting to cut funding for schools or other local government services. But in Portland’s case, that’s exactly what the inclusionary program is likely to do, according to the city’s own budget office.

On the surface, one of the compelling policy attractions of inclusionary zoning (“IZ”)is that it doesn’t seem to cost any money: You require developers to build 1 or 2 affordable housing units for every ten new apartments that they build. Maybe your city offers up a density bonus, or expedites permit handling, but unlike conventional public housing, the city doesn’t have to lay out any of its cash to get more new affordable housing. That’s why Evan Roberts of StreetsMN described it as politically understandable, though terrible policy.

Portland new ordinance is one of the nation’s most demanding inclusionary housing requirements. Basically, the city will require that all new apartment buildings of 20 or more units set aside 20 percent of their units for renters with no more than 80 percent of the region’s median household income (about $56,000). Alternatively, developers could set aside 10 percent of their units for households earning less than 60 percent of the region’s multifamily housing. (As we’ve noted at City Observatory, most cities have far lower inclusionary requirements, offer exceptions, or only apply the requirement to newly up-zoned properties or those projects receiving city subsidies).

The city’s plan includes the usual list of non-cash aid to developers–lighter parking requirements, faster permit processing and density bonuses–although there’s considerable dispute as to whether these effectively allow developers to build more than they would have otherwise.

All of the analyses of the city’s inclusionary zoning plan concluded that unless the city offset the cost to developers, fewer units would get built. As a result, in addition to regulatory concessions, the city is also assuming that new apartment buildings would also get subsidized via a property tax exemption. And, as it turns out, this is where inclusionary housing starts get to costly for the public sector.

Portland’s plan offers up two levels of property tax exemption. For most new apartment buildings, the property tax exemption would apply only to the affordable housing units. For developments with a FAR of 5.0 or more (meaning for example, that a developer is building a 50,000 square foot or larger building on a 10,000 square foot lot), which would typically be an apartment tower, developers would get a property tax exemption for all of the apartments in the building.)

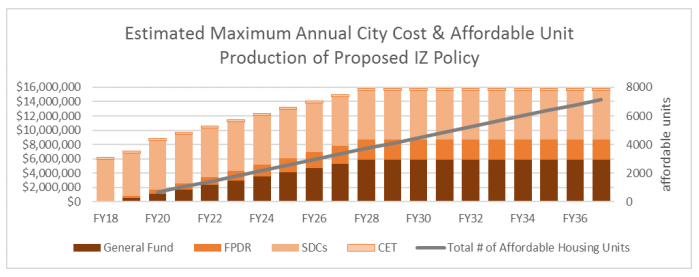

The amount of revenue foregone due to the tax exemptions is difficult to estimate. It depends on whether developers choose to set-aside 10 percent of their units for families at 60 percent of median income or 20 percent of their units for families at 80 percent of median income. It also depends on how many units are actually built. Even with property tax breaks and other incentives, many developers argue that it will no longer be financially attractive to build new apartments in Portland. The City Budget Office has developed estimates of lost property revenue from the inclusionary housing program based on the assumption that developers will mostly go the 10/60 route (which minimizes their construction costs and gets them the largest property tax benefit per affordable unit). They also assume that the IZ program doesn’t impair housing construction–that the city builds as many units as its Comprehensive Plan calls for between now and 2035. Under these assumptions the IZ program will cost the city $15.8 million in tax and fee revenue per year.

The total cost of the property tax breaks and city fee waivers per unit of affordable housing ranges from about $21,000 to almost $220,000 per unit. But the cost to the City of Portland is far less than this amount, because most of the foregone property tax revenue is lost to other local property taxing entities, including K-12 schools, community colleges, Multnomah County and a handful of other local governments. In essence, the City Council voted to have these other taxing entities pay about three-fourths of the fiscal costs associated with inclusionary housing, with the result that these other governments will have less revenue to pay for schools and other local services. Here’s the takeaway quote from the City Budget Office:

CBO Analysis: The proposed policy would result in an estimated per-affordable unit cost that ranges from $20,787/unit to $218,663/unit, depending on project location and incentive package selected. The cost to the City General Fund is less – ranging from $4,674/unit to $57,529/unit – due to the property tax exemption costs being spread across schools, the County and other local public agencies.

In essense, the City has voted for other taxing jurisdictions to pay three-quarters of the public fiscal cost associated with inclusionary zoning.

Whether or not developers will get this volume of tax exemptions is still in doubt. The city doesn’t have exclusive jurisdiction over property tax exemptions, and by mutual agreement with Multnomah County, the city has agreed to abide by a $3 million annual cap on revenue lost to property tax exemptions. The City and County will face a major dilemma in the months ahead as the program goes in to effect. If the $3 million cap isn’t lifted, there won’t be the necessary subsidies to make the inclusionary zoning program attractive enough for developers, and the city’s housing supply will suffer. If the $3 million cap is lifted, the city–plus the county, schools, and other local governments-will have a significant revenue shortfall to make up.

The time-tested adage of economists is “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.” And when it comes to inclusionary zoning we might well add: “There’s no such thing as free affordable housing.”