Like most city lovers of a certain age, I spent many hours as a kid playing SimCity. For readers who are tragically uninitiated, SimCity is one of the iconic computer games of the 1990s, though new versions have been released as recently as 2013. Playing as mayor (or, really, dictator, but more on that later), you shepherded the growth of a city from its very first streets to towering skyscrapers—assuming you weren’t wiped out by tornados, fires, or aliens. By making thousands and thousands of people plan commercial, industrial, and residential districts for their virtual towns, the creators of SimCity have probably done more than anyone in the history of the world to introduce basic principles of zoning to the public.

Recently, I started playing a successor to SimCity, Cities: Skylines (or CS, as I’ll call it). CS is very much like SimCity, with some added details (at least compared to the last version I played) and much better graphics. But unlike when I was ten, I can also appreciate that CS, like SimCity, has a whole host of assumptions about how cities work, and how urban governance works, built into the gameplay—assumptions that are both frustrating as a player and fascinating as someone who spends a lot of time thinking about real urban planning and governance. While all games that simulate real life are of course drastically simplified, the way that they’re simplified often speaks to the actual worldview of the people who design and play them. With that in mind, here are some notes on what a video game can teach us about the biases and blind spots of real-life urban planning in the US:

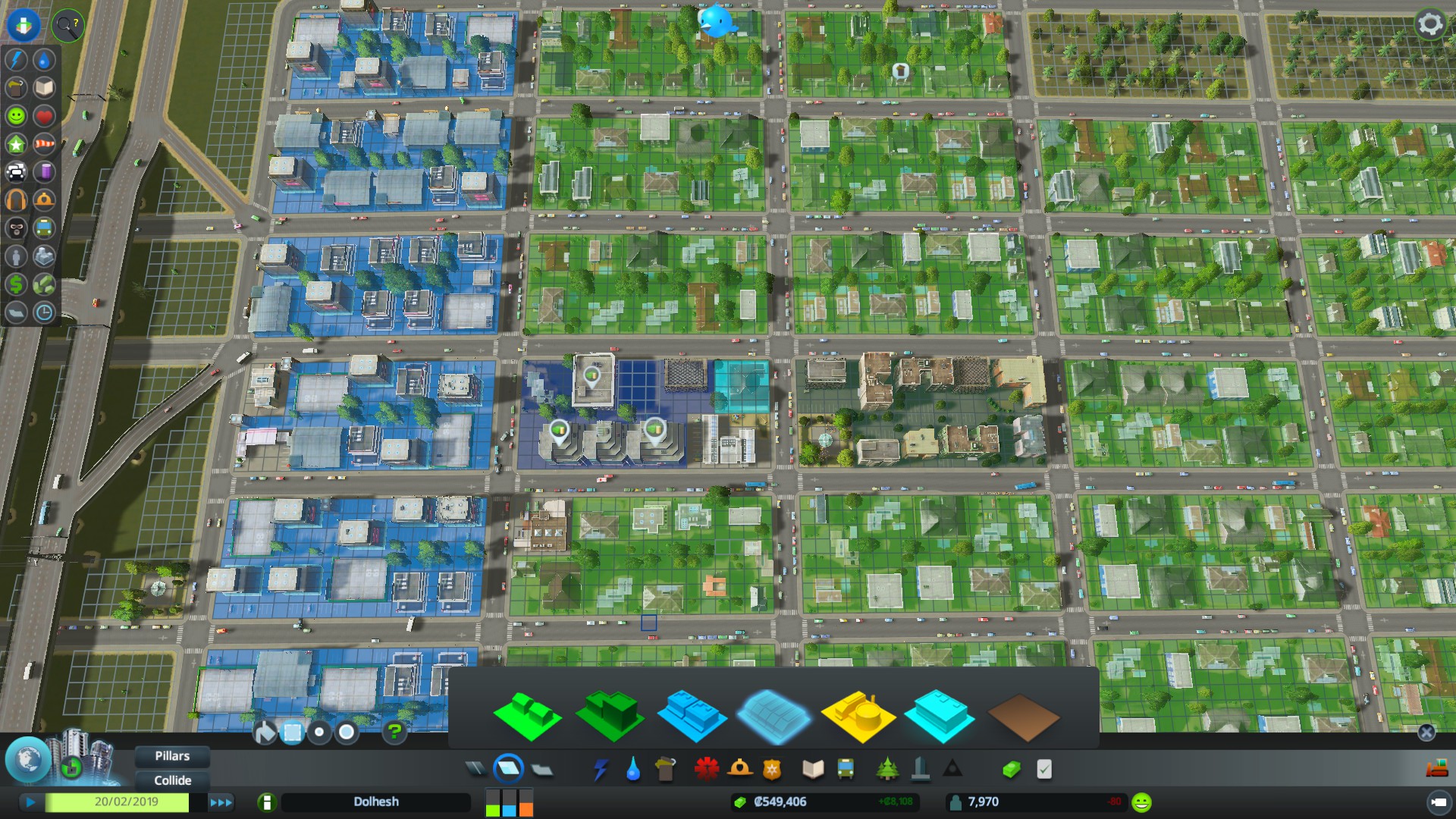

- You must zone—and use single-use zoning. With the exception of some Sunbelt cities, nearly every urban core in America took shape in an era before zoning. As we’ve written, brownstone Brooklyn, Wicker Park in Chicago, Cooper-Young in Memphis, and any number of pre-WWII neighborhoods across the country—not to mention iconic cities in other parts of the world—could only have been built without modern American zoning, with its density limits, parking requirements, and separation of shops and homes. But in CS, no one can build anything on a plot of land until you’ve given it a zone: Residential, Commercial, Industrial, or Office, and specified high- or low-density. It’s striking that zoning is so baked into our assumptions about how urban development works that leaving something unzoned is just not possible—let alone creating mixed-use zoning, form-based zoning, or other kinds of development regulations like those used in Europe.

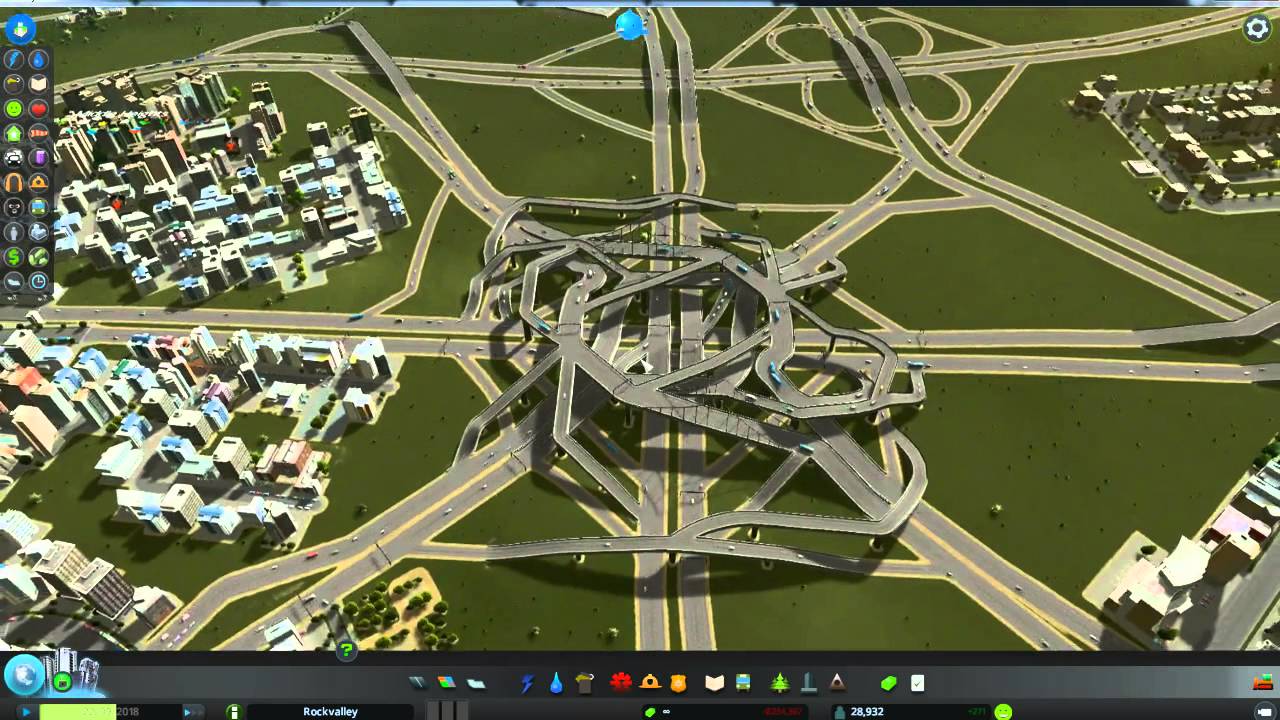

- You must give cars primacy on the street. One of the most important tools real-life planners have is designing public space, including streets. The tradeoff between pedestrian spaces, bike lanes, and lanes for motorized traffic—and within motorized traffic, between private vehicles and public transportation—has a profound effect on neighborhood character, development patterns, and how people choose to get around. But in CS, that decision has been made for you—and as with zoning, the assumption is that all streets will follow the mid-to-late-20th-century US norm, which is dedicating as much space as possible for the use of private vehicles. Pedestrian-only and pedestrian-dominated streets, transitways, or simple bus lanes are all impossible, even though, again, many real-life neighborhoods around the world would be very, very different without them.

- Parking doesn’t exist. This is an interesting one: whereas the last two issues bake in assumptions based on 20th century US practices, when it comes to one of the defining features of modern urban land use in America—parking—CS simply pretends it doesn’t exist. Why would it do that, when the game takes so much care to have a sophisticated transportation model, with individual workers who have to get to jobs, creating traffic jams, or using specific bus or train stops? Here’s one theory: no one actually wants a city full of parking lots and multi-story garages. Put simply, accommodating the actual demand for parking that your little citizens generate would be a bummer, because half of the buzzing streetscapes or idyllic suburbs you created would be erased for parking lots. This is, in fact, what we have done in real life, and it is a bummer. But CS might have forced players to look at parking as a part of the transportation system—and to recognize that the attractive, non-parking-lot-based neighborhoods in which many people wish to live their lives are incompatible with massive car use. Instead, it just pretends that all the costs associated with car storage don’t exist—a form of denial that is still strong more than ten years after the publication of The High Cost of Free Parking.

- It’s all about the built environment. CS presents cities as a kind of dynamic puzzle, a system with inputs and outputs that can be optimized towards whatever goal you might have for them. But in real life, cities are mostly about people, and the relationships between them. Interestingly, though in many ways the game locks in an incredibly specific time and place—America in the second half of the 20th century, more or less—many of the defining features of that era are entirely absent. There are no poor neighborhoods in CS; race doesn’t exist, so there are no segregated black or white or Asian or Latino neighborhoods, either. In fact, community does not exist in any form. Every person cares only about their individual inputs and outputs: finding a job, having a means of transportation to the job, and so on. But for many real people, community is what cities are all about. Moreover, a central tension in urban governance is reconciling the design of the built environment with the goals of the people and communities who live in it. It’s disappointing that at least one version of the planners’ fantasy resolves that tension by simply imagining people and community out of the equation.

- There are no politics. It would take a special kind of weirdo (like me) to play a game where you have to negotiate funding for major infrastructure projects with representatives from your state’s DOT, and get a community organization’s approval for every new apartment building. But those politics are, in fact, central to how cities get built today. In CS, you don’t really answer to anybody, which, obviously, is part of the fun—but it also represents a particular fantasy that has dogged urban planning since its beginning: namely, the myth of planning as engineering, a quasi-scientific exercise in tweaking traffic flows and directing people and jobs to the optimal locations to achieve a unified vision. In real life, every decision that gets made has a coalition of interested parties behind it. Understanding those interests, and the government institutions through which they’re channeled, is as important to understanding urban planning as a traffic model or supply and demand curve.

Even though it’s just a computer game, Cities: Skylines has a lot to teach us about the unstated premises of our urban planning conversations, and demonstrates how those premises profoundly shape what our cities can look like. When we assume the necessity of a given way of regulating cities, assume away the messiness of people and their relationships, assume away politics, and ignore major costs, we miss an awful lot of what urban planning debates should be.