What City Observatory did this week

Talkin’ ’bout my gentrification. Jerusalem Demsas of Vox has a thoughtful synthesis of what we know about gentrification. If we’re concerned about poverty and inequality, gentrification is far from the biggest problem we face. Gentrification is surprisingly rare, and while it brings inequality into sharp focus, there’s precious little evidence of widespread harms.

The bright spotlight shining on a relative handful of gentrified neighborhoods hides in the shadows the real and far more pervasive problem of concentrated poverty. And, as we’ve written at City Observatory, the myopia of gentrification scholarship means that few studies every consider the counterfactual case of asking what happens to people who live in poor neighborhoods that don’t rebound. The most common anti-gentrification tactics—blocking new market rate housing—actually make housing affordability and displacement worse.

Must read

1. What is the conservative position on zoning? Libertarianism, local control or “owning the libs.” Writing at the bloc Pocket Track, Alex Schieferdecker has a thoughtful essay digging into conservative politics and political philosophy as applied to land use. There’s a division on the right, according to Schieferdecker. Philosophically, the libertarian and less-government conservatives ought to be opposed to most land use controls, which ought to put them in league with the YIMBY activists. After all, what is single family zoning but a constraint on the property rights of a landowner. Meanwhile–and with a substantial boost from Donald Trump and right-wing media–other conservatives have come out swinging to protect the ability of governments to strictly regulate property (as long as they’re local governments and they’re regulating out apartments).

The underlying divide between right wing pro-zoning politicians and latent-YIMBY libertarians has everything to do with zoning’s key role in establishing and enforcing class and racial divisions. As Schieferdecker writes:

. . . the intention of the vast majority real-world zoning laws has been to separate people from each other. These laws were originally written explicitly to separate different races until that overt approach was ruled unconstitutional. Cities then seamlessly pivoted to writing zoning laws that separated different styles of housing as a proxy for social classes which in turn were a proxy for race. Not everyone is willing to say it out loud, but the central purpose of much of American zoning remains the preservation of spatial income segregation. The identical idea is instead smuggled into the public conversation under the guise of “protecting property values” or “preserving community character.”

2. Glaeser & Cutler on the shortage of cities. In a Wall Street Journal Op-ed that previews a key theme from their new book—”The Survival of Cities”—economists Ed Glaeser and David Cutler voice a familiar theme: Many thriving desirable cities, especially in California, have blocked the construction of new housing that would allow more people to participate in their productive thriving economies. Blocking housing construction in productive cities pushes up home prices, leads to sprawl and lengthened commutes, and contributes to greater energy use and greenhouse gas production. An essential first step, according to Glaeser and Cutler is getting state legislatures to mandate that local governments allow more housing, something that is starting to happen, but in their view needs to go considerably further.

With housing, the key actors are state legislatures, because they can rewrite the rules of local zoning on a dime. Last month, the California legislature passed a law that could make the permitting of two-unit projects far more automatic. It’s a good beginning, but states should go further and only allow localities to impose regulations and rules that have gone through rigorous cost-benefit analysis.

Overall, this op-ed echoes a key theme we’ve pursued at City Observatory: the demand for cities and urban living has far outstripped the supply of great urban places. Improving our cities, and building more housing in the places where demand and opportunity are abundant is a key to addressing many national challenges.

3. American’s don’t really hate density. The latest version of a Pew survey on America’s residential neighborhood preferences has invited a wide range of punditry. The survey claims to find that by a 60 to 39 percent margin, Americans would prefer to live in larger homes, more distant from schools, stores, work and other common destinations. While some see the demise of urbanism, or the lingering effects of the pandemic, we think Alex Pareene has a far more nuanced take. The question of the idea community has gotten bound up in the culture wars: The real motivation has less to do with urban form than the ability to determine who one’s neighbors are:

White Americans want an endlessly appreciating asset and the ability to police who their neighbors are and what they do. Housing segregation, suburban sprawl, and planned communities are how they won those things, and how they protect them. Automobile dependence is mainly a necessary side effect.

As Pareene points out, when it comes to vacationing at Disneyland or going on an ocean-cruise, middle and upper class Americans have no resistance to dense, car-free environments–they even pay a premium for the privilege. What’s really at work are issues of class and control.

New Knowledge

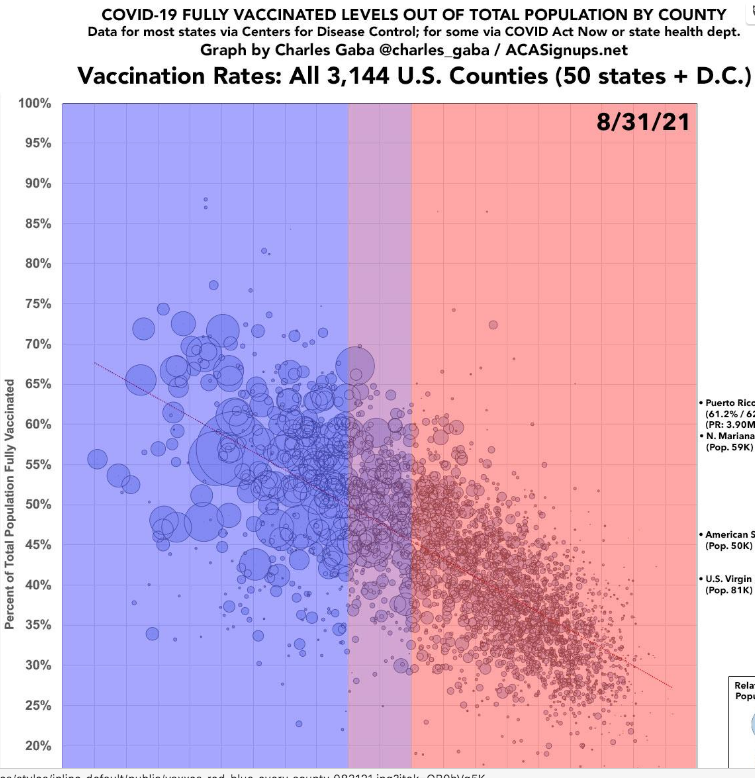

The red-blue dimension of Covid vaccination. New data on county level vaccination rates underscores how the profound political divide in the United States is affecting public health. People who live in counties that voted most strongly for Joe Biden have the highest rates of vaccination; those who voted for Donald Trump have the lowest. The following scattergram, using the red/blue partisanship convention shows vaccination rates of US counties as of August 31, with county population proportional to bubble size. The fitted regression line implies that on average a county that voted 65 percent for Biden had about a 55 percent vaccination rate, while a county that voted 65 percent for Trump had a 40 percent vaccination rate.

Over the summer, the relationship between county partisanship and vaccination status has grown steadily stronger. In the Spring, county vote for President explained only about 5 percent of the variation in vaccination rates across counties; today it statistically explains about 45 percent of the variation. Unlike the previous waves of the pandemic, when there was no available vaccine, the current wave, driven by the Delta variant is plainly a product of our political division.

Charles Gaba, Weekly Update: U.S. #COVID19 Vaccination Levels By COUNTY & Partisan Lean, ACAsignups.net, August 31, 2021.