What City Observatory did this week

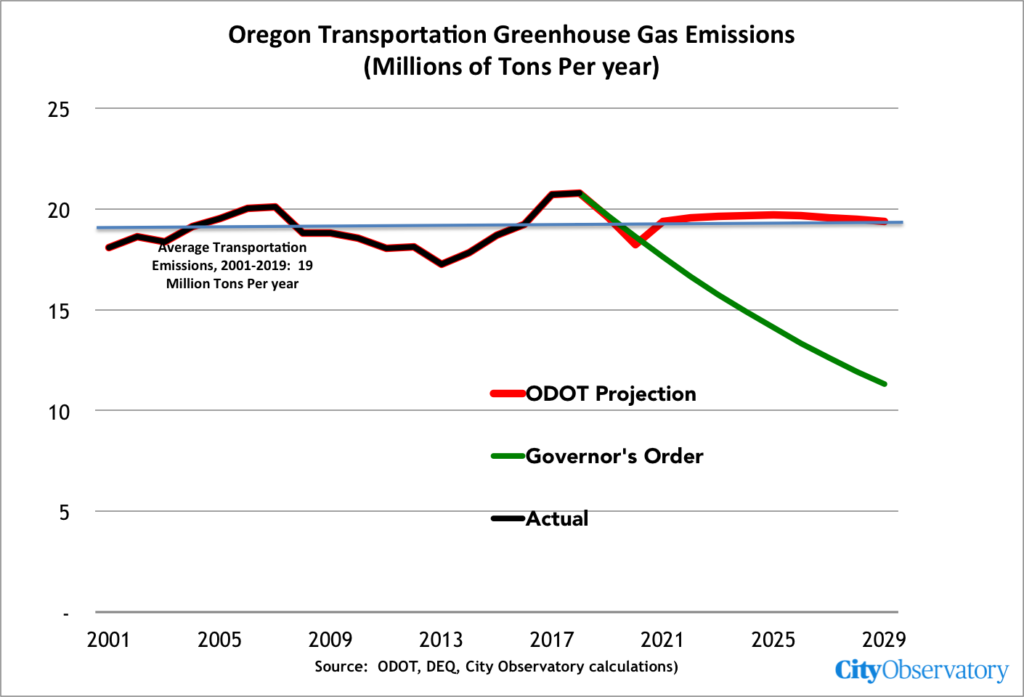

1. ODOT’s real climate strategy: Pollution as usual. Oregon’s highway builders are keeping two sets of books, one claiming that it cares about climate issues, the other shows that its financial plans depend on never reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The Oregon Department of Transportation has a glossy, highly promoted and hopelessly vague “climate strategy,” replete with statements of concern, palliative suggestions and a green fig-leaf logo. But the agency’s true plans are reflected in its budget and financial documents. The agency’s revenue forecast shows that its planning for—and counting on—burning just as much gasoline, and creating just as much greenhouse gases at the end of this decade as it does now.

These financial projections—which ODOT presents to bond markets as evidence of its best estimate of future conditions—show that Oregon transportation emissions won’t decrease at all through 2029, and will fall vastly short of the greenhouse gas emission reductions pledged by Governor Brown and mandated by state law. These financial projections show that this agency is cynically keeping two sets of books when it comes climate: one, for public consumption that pretends to care, and a second set, that reflects its real intent to continue polluting as usual.

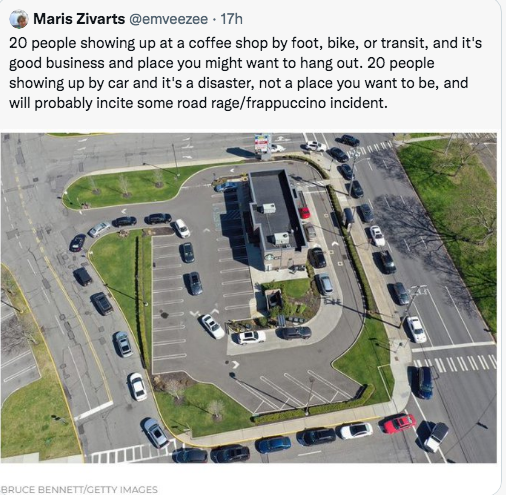

2. Drive-thru restaurants are making cities less livable and killing the planet. Drive-thru’s for restaurants, coffee shops, banks and other retail establishments are some of the most city-soul crushing infrastructure imaginable. They take up space, create a desolate and pedestrian hostile environment, and cement car-dominance. And more than that, idling while waiting to pull up to the window and receive your order produces pollution. We estimate that your twelve ounce latte, dispensed at a drive-in window generates as much as a pound of carbon.

Must read

1. Our self-imposed scarcity of nice places. Strong Town’s author Daniel Herriges nails it in this essay: our urban problems in the US stem from a profound shortage of nice places, a problem that is almost entirely self-inflicted: We’ve made it illegal, through zoning, lot setbacks and by making urban spaces safe for cars, to build the kinds of places American’s most prize (dense, interesting, walkable, mixed use neighborhoods). The fact that such neighborhoods are so rare makes them expensive: They’re prized and in short supply, which tends to drive up their prices. Herriges:

In fact, our shortage of nice places is almost totally self-imposed. And it’s precisely because 98% of the North American built environment is so blah that the 2% of places that are really well-designed environments quickly get bid up by the rich and become inaccessible to the rest of us. The solution to this isn’t to stop creating such places, but to create vastly more of them.

And that correlation between great urban places and high prices has gotten so fixed in the mind of many that there’s a tendency to equate neighborhood improvement with gentrification. The irony, of course, is that many of today’s great urban neighborhoods were originally constructed as middle class working man’s housing; it’s only because it’s not possible to build more such housing today that such places are unusual and therefore expensive. The solution to our affordability problems is to legalize dense, mixed use urban neighborhoods so that everyone has access to them.

2. More cycling would reduce traffic congestion, lower greenhouse gas emissions, improve health and create jobs. A study of London looked at the likely impacts from raising that city’s cycling mode share from its current 2 percent to 14 percent. It found that this would generate a number of benefits, creating more local jobs in the cycling sales and service.

It would also reduce car driver trips by around 4 billion vehicle km by 2030 and associated greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 680,000 tonnes. This increase in cycling will produce wider economic benefits of the order of £4.8 billion by 2030. As well as bikes replacing car passenger trips, cargo and e-cargo bikes have the potential to replace up to 7.5% of van mileage by delivery and service companies, and associated carbon, pollution and congestion. A cycle mode share of 14% by 2030 would also create over 25,000 additional green jobs. . . and these are jobs that can be created quickly.

Rather than building more freeway capacity, if cities were to invest in more cycle infrastructure, more shared cycle systems, and incentives for e-bikes, they’d make vastly greater progress in reducing greenhouse gases, and making cities healthier, more prosperous and more livable.

New Knowledge

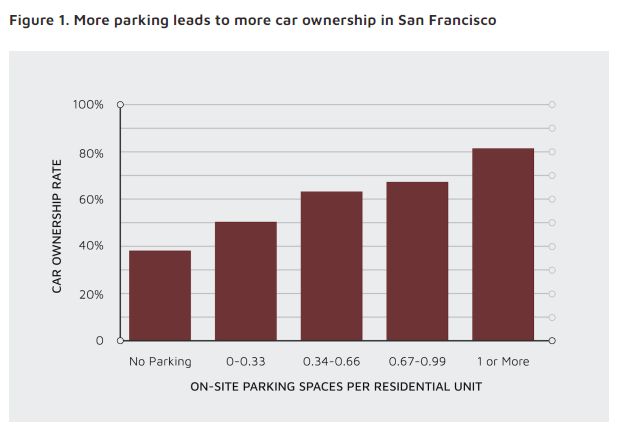

Parking and transportation behavior: A natural experiment. We’ve long know that the shape of the built environment (density, transit access, parking availability) influences travel decisions. But simply observing that people in say, denser neighborhoods walk, bike or take transit more often than others isn’t necessarily compelling that density is a cause; it could just be that people who like to walk, bike and ride the bus choose to live in denser neighborhoods.

The research gold standard for ferreting out the cause-and-effect connections between such phenomena, is the randomized trial. In general, it’s hard to do randomization, but a housing lottery for affordable apartments in San Francisco provided just such a random pool for researchers to study. Thousands of people entered the lottery for these newly built units, and were assigned randomly to apartments with varying housing and neighborhood characteristics (density, transit access, available parking spaces, etc). Researchers surveyed these lottery winners about their travel habits to estimate how different aspects of the built environment of each apartment correlated with travel patterns.

Their core finding amplifies the work of Donald Shoup: The price and availability of on-site parking had the largest observable effect on car ownership. The car ownership rate for households living in buildings with no on site parking is less than half what it is for apartment buildings with one or more parking space per unit–the standard required by zoning in many communities.

They conclude that parking is a powerful, and under-appreciated policy lever for improving transportation and livability in urban settings:

Our findings suggest that the potential for fewer private automobile trips is large and does not depend on car-free households relocating to car-free buildings, or on people who like to ride transit moving to transit-rich neighborhoods. We show that household decisions on car ownership and travel depend on transit accessibility and walkability, but even more so on parking supply. . . . Where streets are relatively walkable and transit service is frequent, parking emerges as the key factor shaping household travel behavior — and parking is a factor that is highly amenable to low-cost policy reforms that can rapidly provide benefits.

The author’s also tackled another claim: That those without easy access to parking (and therefore ability to commute by car) would be disadvantaged in pursuing employment opportunities. The researchers found no correlation between parking availability and employment outcomes for survey participants.

Adam Millard-Ball, Jeremy West, Nazanin Rezaei, Garima Desai, “What Do Residential Lotteries Show Us About Transportation Choices? Actually, quite a lot., Transactions, Issue 8 | December 2021

In the news

At the Oregonian, Ted Sickinger writes that “Oregon will fail its climate goals if ODOT acts on big freeway projects.” The article quotes City Observatory research documenting the Oregon DOT financial projects showing that the agency has no intent or expectation that its efforts will produce any reduction in transportation greenhouse gases through 2029, in violation of Governor Kate Brown’s environmental executive order. Sickinger also notes that OregonDOT has simply ignored Governor Brown’s direction to evaluate road pricing as a way to avoid expensive, unnecessary freeway projects and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.