What City Observatory Did This Week

Still Unaccountable: Oregon’s highway department has a cost overrun problem, so naturally they hired consultants to fix it. The twist? Those same consultants have their own impressive track record of blowing budgets and breaking rules.

The new “roadmap for accountability” comes courtesy of AtkinsRéalis-Horrocks, whose principals Shane Marshall and Joshua Laipply recently departed Utah and Colorado DOTs (respectively)—both agencies with spectacular cost problems during their tenures. Marshall oversaw Utah’s I-15 expansion, which doubled from $1.7 billion to $3.7 billion after legislative approval. Laipply’s Colorado DOT spent twice the national average on consultants and violated state contracting laws.

Now both work for consulting firms eager to expand in Oregon. Marshall is literally the “Chief Revenue Officer” at Horrocks, leading their “StateDOT expansion strategy.” Meanwhile, Laipply’s firm just paid $300 million for Portland’s David Evans & Associates—the same firm that is the second largest contractor on the Rose Quarter—a project that has more than quadrupled in price—and that a decade ago billed $44 million on the failed Columbia River Crossing, with $17 million in “questionable” charges.

Their recommendations are largely a rehash of old gimmicks that didn’t work: Create a “major projects office” (ODOT established one in 2019), build a project dashboard (they’ve had one since 2022), form an oversight committee (the legislature created two in 2017), and implement “RACI” management frameworks (McKinsey recommended this in 2016, and ODOT already uses it).

Least surprisingly, a key recommendation is that ODOT ought to hire more consultants with “substantial public sector expertise”—i.e. firms exactly like Marshall’s and Laipply’s. It’s consulting inception: consultants recommending that agencies hire more consultants to fix problems caused by hiring too many consultants.

Must Read

Shops are important for urbanism. Noah Smith has a compelling essay on why urbanists need to pay much more attention to the retail environment. A dense, diverse collection of shops is an essential element to neighborhood vitality. He argues:

The beauty of Brooklyn’s brownstones, or Paris’ Haussmann apartments, comes in large part from the fact that they’re located near to shops. When you see those narrow streets in front of the Brooklyn apartments, you know they’re built for walking.

In Portland, their are dozens of “food cart pods” populated by hundreds of food carts, providing the kind of diverse assortment of choices one finds the densest urban centers in the world.

One of the most important points that Smith makes is having lots of small businesses is very much preferable to having a few large ones. More small businesses mean much more variety and choice.

Small businesses are not economically efficient, but they create some positive externalities for cities. The higher a density of small retail businesses you have in an urban area, the more novelty local consumers can enjoy, and the more serendipity people can get from just walking around.

The policy implication of this is that we ought to be encouraging very small-scale activity in cities. Some policies, like maximum store sizes, might also level the playing field for smaller businesses.

. . . it’s significant enough that there have been financial impacts to the organization,” she said. “When these buildings don‘t cashflow as anticipated, it means a reduction in services we’re able to offer the residents.”Margaret Salazar, chief executive of Reach Community Development, a nonprofit with one preference policy building, said its building alone has an 11% vacancy rate, which means around 17 apartments are sitting empty and unused.

New Knowledge

The mobility-productivity paradox. Victoria Transportation Policy Institute’s Todd Litman has a newly updated and expanded version of his paper exploring the paradox between mobility and productivity. The paradox is this: places where people travel more have lower levels of productivity.

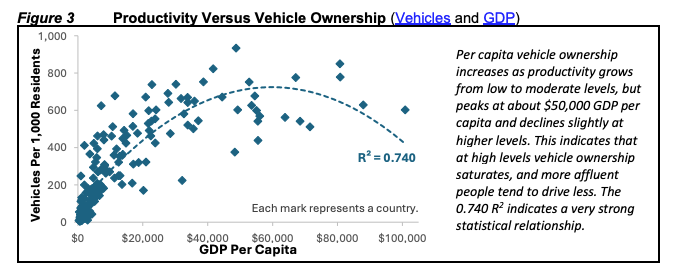

A fascinating chart shows the relationship between aggregate productivity (GDP per resident) and car ownership for the different countries. For lower income countries, productivity has a positive relationship with vehicle ownership; but that relationship appears to turn negative for countries that have a GDP per capita of $60,000 or more. The lowest income countries can’t afford many vehicles, and vehicle ownership increases with overall productivity, but only to a point.

While its true that more productive places have higher incomes and can afford greater travel expenditures, there are many ways that excessive mobility can negatively affect economic productivity.

. . . increased vehicle travel can reduce productivity including higher user, infrastructure and external costs; more automobile dependency and sprawl that reduce accessibility and mobility options; less local productivity; and less attractive urban environments. These impacts filter through the economy, reducing productivity, incomes, economic opportunity, property values and tax revenues.

Many of the productivity sapping effects of excess mobility are related to externalities and public sector costs. Crashes, pollution, congestion, and auto-dependent development patterns require all households in a region to endure higher costs. And many of these costs are shifted to the public sector, a classic example being the costs of induced travel associated with expanded highway infrastructure.

Todd Litman, The Mobility-Productivity Paradox: Understanding the Negative Relationship Between Mobility and Economic Productivity, 29 May 2025, Victoria Transport Policy Institute.