What City Observatory Did This Week

Unaccountable. The Oregon Department of Transportation is unaccountable for routine cost overruns on major highway projects. Nothing it has done has acknowledged or solved this decades old problem, and giving it billions more will fuel further cost overruns. ODOT’s Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) misleadingly claim that 97% of projects are completed under budget. ODOT is careful to define overruns only as costs after contracts are awarded: this conceals ODOT staff’s consistent pattern of low-balling cost estimates to get projects approved. ODOT also has a practice of “re-baselining” a project—retroactively altering the initial cost estimate to conceal cost increases. ODOT’s project database omits every large project that has experienced a cost overrun. The agency’s Transportation Project Tracker dashboard lists only six tiny projects as having experienced cost overruns.

For example, there’s no mention of the Abernathy Bridge which has gone from $248 million to $815 million. In recent correspondence with concerned citizens, ODOT staff simply omitted initial cost estimates, covering up a 47 percent cost overrun on the Iowa Street I-5 Viaduct project.

Magical thinking on stadium finance. Baseball stadium proponents are arguing a “jock tax” would be free money to pay for a stadium. That’s based on an illusion about where the money to pay baseball players income comes from. The economic evidence is that sports venues just re-allocate money in the local economy. Diverting Oregon income taxes to subsidize stadium construction subsidizes billionaire owners and millionaire players at the cost of other public services.

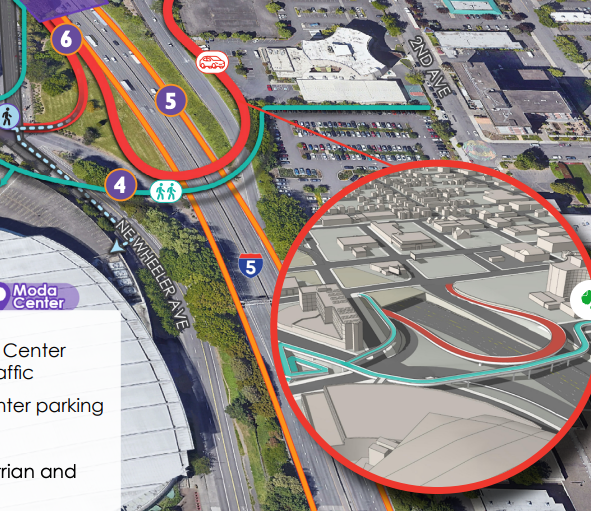

The Rose Quarter’s Deadly Hairpin Off-ramps. The proposed design of the $2.1 billion I-5 Rose Quarter Project includes two deadly hairpin freeway off-ramps. Everyone focuses on the part of the Rose Quarter than involves covering over part of the I-5 freeway. No one ever talks about the two deadly off-ramps ODOT will build as part of this project.

Traffic exiting I-5 South at the Rose Quarter will go through a high speed tunnel and then choose between two hairpin turns on to local streets. Similar ramps in Portland and Seattle are the source of frequent crashes and fatalities.

Must Read

The Climate Impact of Highways law has a mundane name that (probably deliberately) understates its design. It requires the state’s transportation agency, and eventually other public works departments, to offset increases in carbon pollution and vehicle miles travelled (VMT) anytime they expand a highway. Because it focuses on specific, measurable outcomes, it aims to adjust the planning processes for the state’s massive highway bureaucracy.

- I-35 in Austin, Texas

- NY State Routes 33 and 198 in Buffalo, New York

- Interstate I-980 in Oakland, California

- Interstate 45 Expansion in Houston, Texas

- Interstate 175 in Saint Petersburg, Florida

- IL 137/Amstutz Expressway/Bobby Thompson Expressway in

- Waukegan and North Chicago, Illinois

- DuSable Lake Shore Drive (US 41) in Chicago, Illinois

- US-101 in San Mateo County, California

- US-35 in Dayton, Ohio

No single policy reform will turn things around, but members of the San Francisco County Transportation Authority, who are also on the Board of Supervisors, recently revisited one idea that could come close: congestion pricing. The case for congestion pricing is simple. When people drive into a highly trafficked area, they impose costs on the people around them. Each additional car adds to congestion, degrades noise and air quality, and worsens the risk of harm for pedestrians and cyclists. Congestion pricing forces drivers to mitigate these costs by paying a fee to the public that compensates for the added nuisance, pollution and risk.

The evidence is when you try it, you like it; a public sentiment (and political leadership) have shifted firmly in support of the measure, which is daily making things better in New York. How about “proven,” instead? Or maybe we stick to supposedly “uncontroversial” measures–like widening roads–that don’t solve the problem, cost billions and make pollution and climate change worse?

The evidence is when you try it, you like it; a public sentiment (and political leadership) have shifted firmly in support of the measure, which is daily making things better in New York. How about “proven,” instead? Or maybe we stick to supposedly “uncontroversial” measures–like widening roads–that don’t solve the problem, cost billions and make pollution and climate change worse?New Knowledge

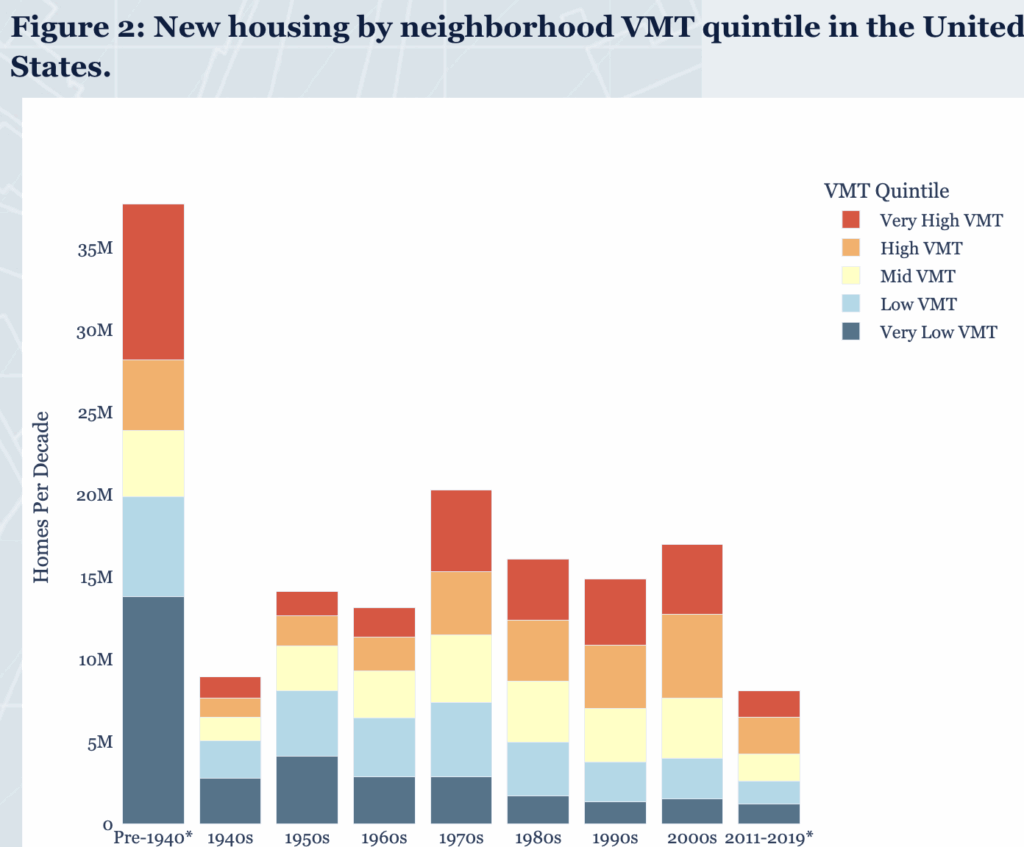

Which cities are building the most new housing in walkable, sustainable locations? The Terner Center has an exciting new report on where cities are building new housing. For decades, the pattern in the US has been continual sprawl and urban expansion, which has meant that much, if not most of new housing gets built in locations with high degrees of car dependence and sprawl.

Meanwhile, we know from our research and that of others that urban neighborhoods with high degrees of walkability are highly prized by consumers and produce a measurable green dividend, in terms of convenience and lower transportation costs. Planners in many cities have aimed to encourage more construction of housing in denser, more accessible neighborhoods.

The Terner study looks across the United States to identify where new housing has been built in these high accessibility, less car-dependent locations. They’ve looked at all the new housing built between 2001 and 2019, and stratified it according to the typical amount of driving in the neighborhood. Technically, census tracts are grouped into quintiles according to the average amount of driving (VMT or vehicle miles traveled) and the study counts the number of new homes built in each quintile in each decade. As the following chart shows, much of the “very low VMT” (highly walkable) housing dates from before 1940, and the housing built more recently is in disproportionatley in high and very high VMT categories.

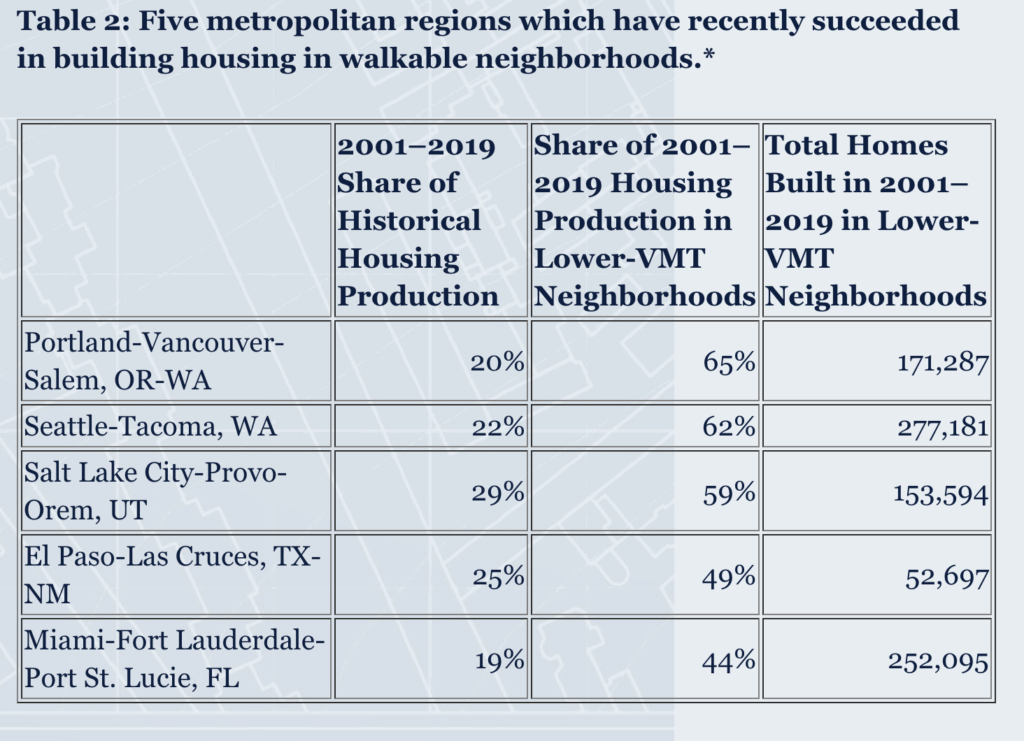

Several cities in the US have managed to build considerable amounts of new housing in “low VMT neighborhoods”–i.e. neighborhoods where people don’t drive as much. According to the Terner Center’s analysis, Portland, Oregon has built the largest share of new housing in low VMT neighborhoods of any large US city that grew by more than 15 percent after 2000. Terner calculates that Portland built almost two thirds of its new housing in the past two decades in “lower-VMT” neighborhoods. Four other metro areas had close to half or more of their new housing in these less car-dependent locations.

This is an important research contribution: It connects housing, transportation, and sustainability in a clear way, and shows how some cities are succeeding in getting more housing built in locations that are both more sustainable and more affordable. It’s definitely something land use, housing and transportation planners ought to carefully study.

Next week, Terner Center will be hosting a webinar` of the study’s findings. You can tune in and learn more Wednesday, May 28, 10:00 – 11:00 am PT, register here.

Building Housing in Walkable Neighborhoods: Are U.S. Cities and States Making Progress?, Terner Center for Housing Innovation, University of California, Berkeley, May 22, 2025. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/building-housing-in-walkable-neighborhoods-are-u-s-cities-and-states-making-progress/