What City Observatory Did This Week

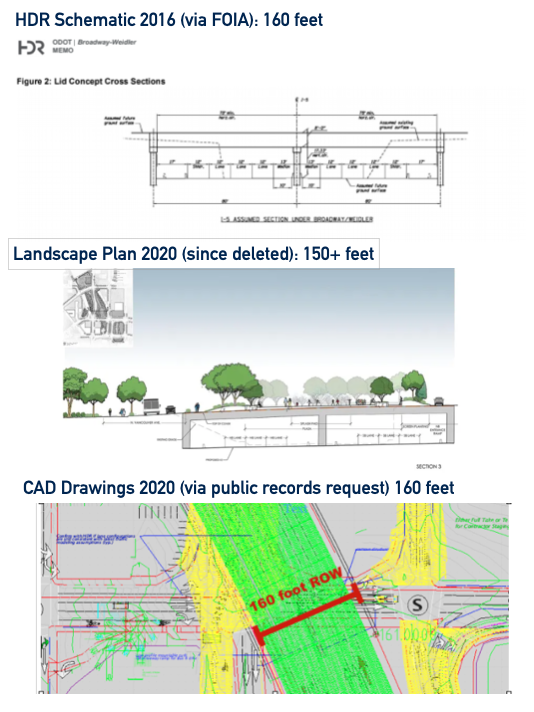

ODOT’s Deceptive Rose Quarter Freeway Expansion. For six years, the Oregon Department of Transportation has systematically concealed plans to build a massive 160-foot-wide freeway through Portland’s Rose Quarter—not the modest “auxiliary lane” project they’ve publicly claimed.

Documents obtained through public records requests reveal ODOT knew since at least 2016 that they planned a roadway wide enough for 8-10 lanes, yet repeatedly refused to answer direct questions about the project’s width. When pressed by City Observatory and others, ODOT officials provided misleading information, non-answers, or demanded formal records requests for basic project dimensions.

The agency published deceptive, not-to-scale illustrations in their Environmental Assessment while hiding detailed engineering drawings that showed the true scope. Metro has called ODOT’s claim that this isn’t a freeway expansion “not objectively true and potentially misleading.”

This massive expansion would generate significantly more traffic and pollution than ODOT admits, severely impacting neighborhood livability—exactly why they’ve worked so hard to hide it.

Must Read

A power analysis of NIMBY politics. Writing at The Nation, Nate Resnikoff has a thoughtful examination of the power imbalances that affect housing in the United States. A standard leftist analysis of housing asserts that corporate power is responsible for high housing costs; that a combination of greedy developers and hedge-fund financiers are driving up housing costs. That misses all of the basic facts about housing in the US: most housing is owned not by corporations, but by individual households; roughly two-thirds of all American households own their own homes. Housing ownership and development are remarkably un-concentrated. The real power in US housing markets is wielded largely by “home-voters”– homeowners who dominate local electoral politics and public meetings, and generally obstruct change, and make it difficult and expensive to build more housing. Resnikoff also points out there isn’t a lot of nuance in the standard Marxist analysis of business interests: landlords (rentiers) benefit from obstructing new development, and by expanding supply, developers undermine the profits of the existing landlords. As it turns out though, developers, who are largely local, also fight liberalizing housing construction, usually because their profits stem from their mastery of the politics and arcane local regulations.

To the extent their is a “class struggle” in housing, it is between the ownership class and everyone else.

Much of the class conflict in housing politics takes place not between Big Real Estate and local communities but within communities: Affluent homeowners, particularly when they are organized into neighborhood associations, form powerful anti-housing blocs. Political science research has found that the people most likely to speak out against housing development during public hearings tend to be older, whiter, wealthier homeowners. Their opposition to new construction helps ensure the persistence of regional housing shortages, which drives up rents and locks first-time homebuyers out of the housing market.

The problem with the simple-minded and wrong leftist analysis of power relations in housing is that it overlooks and minimizes the role of NIMBY homeowners in blocking policies that would permit more housing to be built. Ironically, renters have vastly more power in markets with abundant housing than they do in markets with shortages.

Overcoming the limits of incremental development. One of the watchwords of the Strong Towns movement is “incremental”–meaning that development should only take small steps. Many housing policy innovations aim at small scale: allowing accessory dwelling units on single family lots, and changing zoning to allow “missing middle” housing like duplexes. Based on a recent visit to the Clichy-Batignolles neighborhood in Paris, Benjamin Schneider points out, one of the lessons from Europe is that building whole new neighborhoods, at substantial levels of density, has significant benefits.

Obviously, much more housing gets built–which helps address affordability. More subtly, building a high density neighborhood from the get-go helps break the pattern of car-dependence that is effectively a brake on housing development. This new district development pattern also takes advantage of single-stair buildings, thinner building profiles and greater integration of greenspaces, all advocated by Michael Eliason in his book Building for People–which inspired Schneider’s visit to Clichy-Batignolles.

“Much about modern urban development, and especially district-scale development, in other countries is a complete unknown to even practicing professionals on this side of the Atlantic,” Eliason writes in the book. “We have long lacked the syntax to even talk about many of these concepts.”

Rather that retrofitting dense housing, retail and other uses piecemeal, these district-scale developments leave the car out from the beginning, and build at a scale that creates access and complementarity among diverse uses in a district. It’s rare in the US that we see an entirely new district, planned from its inception to be a no-car or low-car environment–only a handful of places, like Culdesac in Tempe, try this approach. It’s often easier to pursue change in a more gradual, atomistic fashion, but breaking the car-dominated pattern of development may require reweaving the whole cloth of urban space, rather than embroidering scattered spots.

British Columbia failing to meet its climate goals. A new report acknowledges that British Columbia will come nowhere close to meeting its adopted goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. By 2030, carbon emissions are expected to decline by 20 percent from 2007 levels, just half the 40 percent reduction promised in the province’s Climate Change Accountability Act. The unsurprising reason–as in the neighboring green states of Washington and Oregon–increased transportation emissions.

In B.C., the largest polluting sector of the economy was transportation, which accounted for 42 per cent of the province’s total emissions in 2022, the report found. The sector saw an 18 per cent increase in emissions between 2007 and 2022, largely driven by commercial trucking.

Even as it has fallen behind in meeting its climate goals, the province has back-tracked on policy, repealing its carbon tax. Now, it faces an even more daunting challenge. British Columbia’s experience with climate echoes the disappointing record of adopting seemingly bold but always distant goals—Vision Zero, anyone? If this is the best that purportedly “green” places can do, is there much hope a political environment dominated by climate denial?

New Knowledge

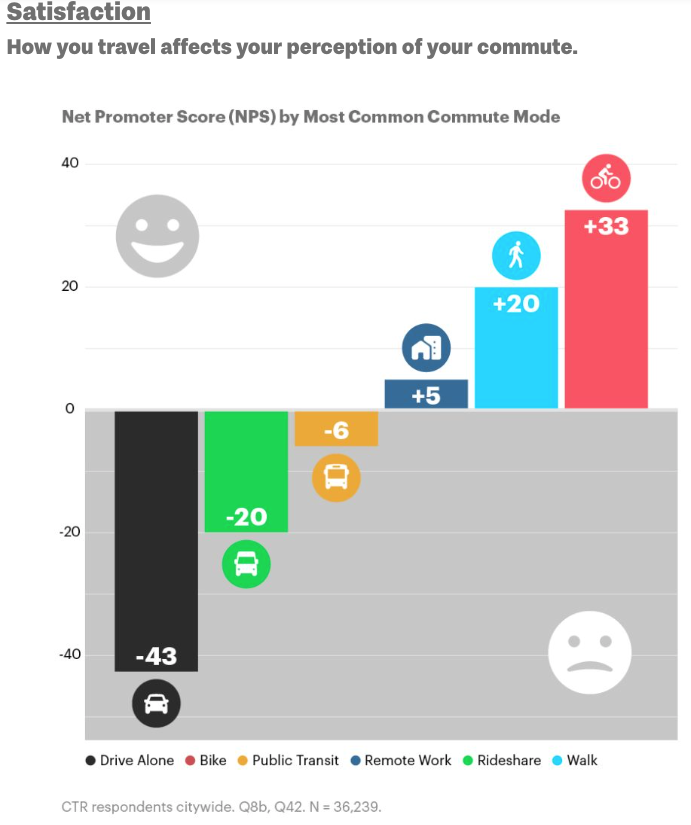

Driving makes you sadder, biking makes you happier. Survey research of Seattle commuters shows that those who commute by car are, on average, very dissatsified, while those who commute by bike are very satisfied. The survey reports a “net promoter score” based on a commonly used marketing question: would you recommend this product (or in this case, transport mode) to others. The net score just subtracts those who wouldn’t recommend a mode from those who would.

Biking and walking have huge positive scores, with more than 33 percent more bikers and 20 percent more walkers recommending their mode vs. those not recommending it. In contrast, drive alone car commuters recommend against their mode by more than 43 points.

Commute Seattle, 2024 Seattle Commute Survey City Wide Report, April 2025, https://www.commuteseattle.com/2024survey/

In the News

BikePortland comments on the dispute between No More Freeways and Portland City Council members about how wide a freeway the Oregon Department of Transportation is planning to build through Northeast Portland.

According to Bike Portland:

When advocates with the nonprofit No More Freeways presented their views on the project at a meeting of the Portland City Council Transportation and Infrastructure Committee on April 21st, they faced very skeptical responses from Councilor (and Committee Chair) Olivia Clark and Councilor Loretta Smith. Yet Clark and Smith have not provided any evidence to back up their skepticism and they appear to be relying on blind faith in the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT).

The Larchmont Chronicle cited City Observatory research showing that improved walkability increases home values.