What City Observatory Did This Week

ODOT’s “Strategic Review”: Conflicted consultants whitewashing mis-management. The Oregon Department of Transportation is again trying convince the Legislature and the public that it isn’t incompetent at managing highway construction. With three major Portland-area highway projects racking up a staggering $4.8 billion in cost overruns in the past five years, the agency has a serious financial and credibility problem. It has offered up a so-called “strategic review” to try to placate criticism but it shows the agency is more interested in image management than actual project cost control. ODOT commissioned a review that reads more like a public relations exercise than a genuine effort to address systemic problems.

The review, led by consultants with deep financial ties to ODOT, doesn’t even try to meaningfully diagnose or solve the agency’s chronic cost overrun issues. Notably, the panel includes former state DOT directors from states with their own significant infrastructure management challenges, raising questions about the review’s credibility.

A revealing study published by the Brookings Institution underscores the core problem: excessive reliance on consultants drives up infrastructure costs. Oregon epitomizes this trend, with its three largest projects generating over half a billion dollars in consulting fees alone. Oregon’s benchmark lane-mile maintenance costs are nearly double the national average.

This isn’t ODOT’s first performative management review. A 2016 McKinsey report similarly offered superficial recommendations, ultimately changing nothing about the agency’s fundamental approach to project management and doing nothing to prevent the continuing avalanche of cost overruns.

The strategic review appears designed not to solve problems, but to create an illusion of accountability—a bureaucratic sleight of hand that serves everyone except taxpayers.

Must Read

. . . congestion pricing is a policy unicorn – it accomplishes a key goal (reducing congestion) and raises money. This is in contrast with highway widenings which are the opposite: they cost money (often billions of dollars) and fail to accomplish the goal of reducing traffic due to induced demand.

Nothing succeeds like excess. Abundance. A new book from Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson asserts that liberals have largely lost their way in actually producing things and have given in to providing widespread veto powers that have crippled the provision of badly needed goods and services. The messaging clearly draws from the emergence of the YIMBY movement which has made just this case for housing. But the Frontier Group’s Tony Dutzik warns that claims about the universality of abundance are simplistic and in many ways wrong. In fact, many of America’s problems stem from an excess of goods and services favored by public policies. As Dutzik argues:

Scarcity is not, by and large, America’s problem. It is, rather, the problems that result from our abundance – the ecological impacts of a high-throughput consumer economy; our failure to replace the sense of meaning and purpose once drawn from work that has since been automated away; the tech-driven stratification of society and accelerating concentration of wealth – that threaten to do us in. These are problems that cannot be “solved with supply.” And failing to keep those problems front of mind in a renewed quest for “more” could wind up making them even worse.

For example, we’re awash in food, thanks to everything from agricultural research to farm subsidies–and yet fresh nutritious food is often scarce and we’re suffering from an epidemic of obesity and poor health due to our diets. Likewise, we have a super-abundance of roads, cars and parking, all of which have fueled sprawl and car dependence, which has contributed to climate change, sedentary lifestyles, and not incidentally, increased social isolation. As the negative effects of social media indicate, even the tidal wave of easy access to data has significant downsides. So the real issue isn’t an inability to produce abundance, its that we produce abundance of things that make us better off.

The city is back. There’s a lot of good news in New York lately. Congestion pricing is working fantastically well. And as Paul Krugman points out, contrary to what many naysayers believe, New York is safe, and getting safer. As Krugman argues, there’s a political dimension to these anti-urban beliefs.

But of course pointing out that life in New York is OK is itself political, because trash talk about our big cities, New York in particular, is a constant theme in MAGA rhetoric. According to Donald Trump, people in New York are afraid to go outside, because they can’t cross the street without getting mugged or raped. Just last Friday Sean Duffy, Trump’s transportation secretary, called the NYC subway a “shithole,” which nobody wants to ride. Spoiler: It isn’t.

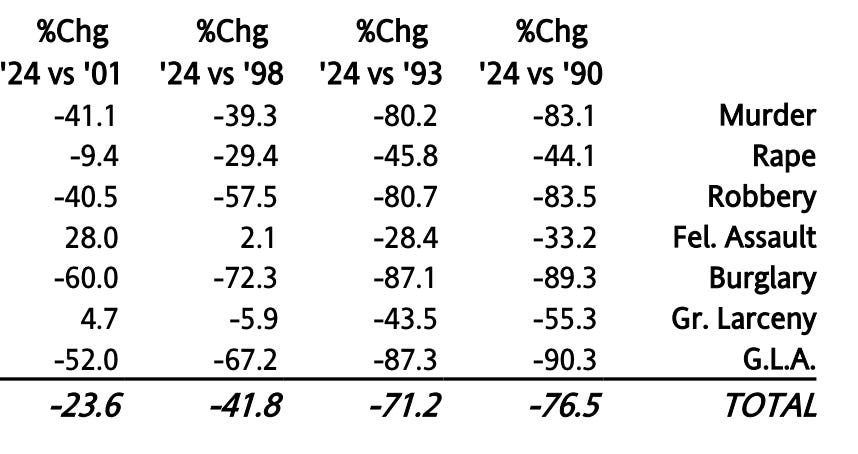

The truth is that New York, which really was a dangerous place a few decades ago, is now incredibly safe. The city’s weekly crime report provides some historical comparisons:

New Knowledge

Real wages rose fastest for low wage workers since 2019. A striking fact about the US economy in the past five years has been scarcely noticed: low wage workers have seen the largest gains in compensation. After decades in which wages became more unequal as higher wage workers saw their earnings increase faster than everyone else, and the past five years have shown big gains among low wage workers that have actually narrowed wage inequality.

The Economic Policy Institute prepared these estimates of wage changes, adjusted for inflation, for ten deciles of the income distribution from 2019 to 2024. Average wages for those in the bottom decile increased by more than 15 percent, higher than any other group and about 2 to 3 times faster than the typical worker (i.e. in the 40th to 60th percentile of the distribution).

And importantly, adjusted for inflation, wages rose for everyone regardless of income decile. The critical difference between this period and earlier decades is that, in the wake of the Covid pandemic, we ran the US economy at much closer to capacity, and held unemployment rates at levels that were previously thought not to be possible (without igniting inflation). Tight labor markets turn out to be a powerful tool for reducing inequality.

Elise Gould, Katherine deCourcy, Joe Fast, and Ben Zipperer, Strong wage growth for low-wage workers bucks the historic trend, Economic Policy Institute, Report, March 24, 2025

Follow City Observatory on Bluesky.