What City Observatory Did This Week

ODOT hiding cost overruns. Despite widespread bloviation about the need for “accountability,” the Oregon Department of Transportation is simply, and inexplicably, unaccountable for the spiraling cost of its largest single project. It’s hiding new higher cost estimates as the Oregon Legislature ponders giving it more morney.

The Oregon and Washington highway departments are once again delaying releasing a new cost estimate for the Interstate Bridge Project. It’s an ominous sign that the cost is going to be much, much higher.

IBR leaders have known since January of 2024 that costs were going to be even higher–but repeatedly they’ve delayed releasing a new estimate.

In April, IBR project director Greg Johnson announced that there would be yet another delay, until at least September 2025– in telling the Oregon and Washington Legislatures and the public how much the IBR project will cost. They now say an estimate will come out “by the end of the year”–i.e. well after the Legsislature will have to vote on a major transportation package.

The IBR cost estimate, which jumped from a maximum of $4.8 billion in 2020 to as much as $7.5 billion in 2022, has grown increasingly stale. Expect the total cost of the project to exceed $9 billion.

Must Read

I love New York. Paul Krugman takes head-on the city-bashing coming from the Trump Administration, including especially Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy. It’s a regularly repeated myth that America’s cities, especially New York are barely habitable hell-holes. It turns out not to be the case.

I live in Manhattan now, and my experience is that if you can afford housing — which is admittedly a huge problem — it’s actually a very good life, with an incredible range of things to do either in walking distance or a short subway ride away. Not everyone wants to live this way, but nobody is saying they should. All we ask is that some Americans be allowed to have favorable views of a place that provides the advantages density and, yes, diversity can offer. But that, of course, is exactly what the U.S. right refuses to accept. New York is one of the safest places in America, yet much of the country insists on seeing it as a terrifying urban hellscape.

Even Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who isn’t as innumerate as Duffy argues the nation ought to be more like Florida and less like New York. The tale of the tape, Krugman points out, shows thats’s simply wrong.

Not everyone wants to live in cities. But many of our problem stem from the fact that not everyone who would like to live in a city can afford to do so. Bashing cities does nothing to address the shortage of cities that affects the nation.

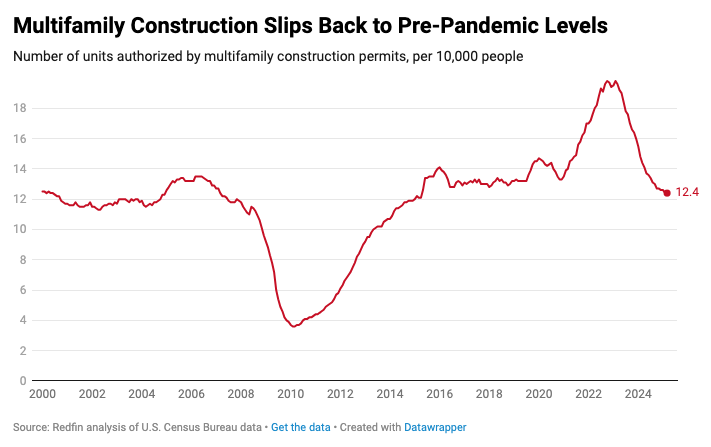

The apartment pipeline is starting to run dry. In an ominous development for future housing affordability, apartment starts are in decline in most U.S. markets, according to data compiled by Redfin. On a population-adjusted basis, the number of new permits for apartments has fallen about 27 percent from its Covid-era peak, and is now below the level it recorded prior to the pandemic. The pattern is widespread: apartment permits are down in about 63 percent of large metro areas.

A temporary surge in supply of newly completed apartments coming on the market, plus an increase in interest rates is leading driving the decline in new starts, according to Redfin:

“New apartments are being rented out at the slowest speed on record and builders are pumping the brakes because elevated interest rates are making many projects prohibitively expensive,” said Redfin Senior Economist Sheharyar Bokhari. “At some point in the next year, the slowdown in building will mean that renters have fewer options—potentially leading to an increase in rents.”

The temporal mismatch between supply and demand (supply changes slowly, and with a lag, while demand can change quickly) is frequently the source of big changes in rents. A continuing decline in new construction is likely to mean a tighter supply over the next few years, putting upward pressure on rents, especially if the economy is strong.

Poor communication and mistrust mark ODOT management. The Oregonian’s Carlos Fuentes has an investigative report chronicling yet more management problems and the financially troubled Oregon Department of Transportation. This time, the bad news is coming from inside the agency, where a recent survey of key staffers showed a range of communication and management problems affecting ODOT’s delivery and operation division. As Fuentes writes:

The agency has urged lawmakers to allocate it more funding this legislative session, while multiple reviews of the agency have discovered faulty communication processes, mismanagement of mega projects and other flaws plaguing the agency.

Agency spokespeople tried to minimize the damage, noting that this is one of several reports addressing the agency’s financial and management problems. We’ve addressed a pair of questionable reports from conflicted consultants, and companies angling to set themselves up with ODOT business. Fuentes notes that there’s no evidence that the latest revealed report has produced any changes:

But it’s unclear if the internal report led to any changes at the agency. Glenn, the spokesperson, was unable to provide any examples of changes that the agency made in response to the report.

As Marshall McLuhan observed, the medium is the massage: Regardless of the substance, seriousness or implementation of any of these reports, they serve to create the illusion that ODOT is somehow coming to grips with its financial and management problems, even though its doubtful they have any real effects.

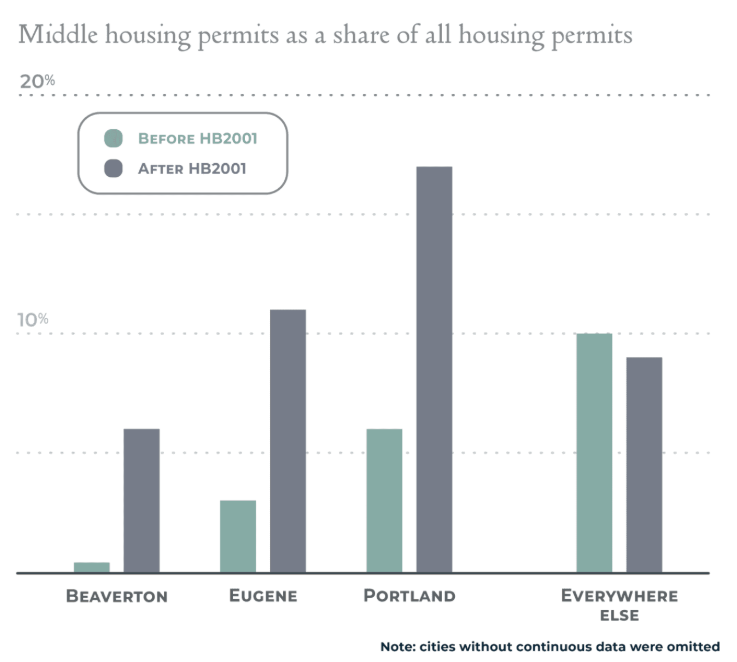

Practical lessons on missing middle housing. Oregon reformed its land use laws in 2019 to generally allow two- to four-plex homes in most single family zoned areas. Sightline Institute’s Michael Andersen reviews the experience to date, highlights some lessons learned, and offers some advice about how the policy (and supporting policies) needs to evolve. In a few cities, the new law has led to a surge in missing middle housing, but in the rest of the state the results have been mixed. That’s not all bad news: it means that the program is working in places where affordability is a big problem. In important respects, the law is working: new middle homes generally sell for a much lower price point than new single family homes.But as Anderson points out, there are a number of tweaks that could make the program more effective.

Among Anderson’s observations: the law should allow new middle units to be either detached or attached to give builders flexibility; the law should allow for larger floor area, so that homes don’t have to be too small, and local development fees can frequently be a barrier.